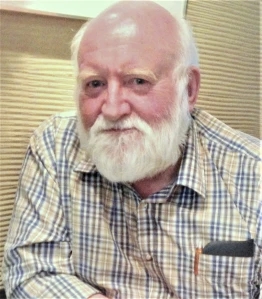

Chris Game

This blog was prompted partly by Vivien Lowndes’ and Phil Swann’s recent INLOGOV blog giving “Two cheers for combined authorities and their mayors”. Substantively, anyway, although the decisive stimulus was the realisation that most, if not all, of those present at the relevant ‘Brown Bag’ session would probably have been unaware that seated among them was the co-author of almost certainly the most comprehensive examination of this topic by any INLOGOV colleague over the years.

I refer to the appropriately labelled ‘long-read’, also masquerading as an INLOGOV blog and entitled Briefing Paper: Elected Mayors, published shortly before the 2017 elections of what I think of as the second generation of elected mayors – and produced by Prof Catherine Staite and a Jason Lowther.

Catherine, nowadays an Emeritus Professor of Public Management, had recently stepped down as Director of INLOGOV, in which capacity she had, among numerous other initiatives, both launched and regularly contributed to our/her blog. And, while I certainly recalled reading the Briefing Paper, I confess that, with his name meaning little to me at the time, I’d forgotten her co-author. Apologies, Jason.

He claimed, moreover, that he himself had “forgotten” it (email, 14/5), which I didn’t, of course, believe … until, a few days later and following some ‘research’, I discovered one of my own INLOGOV blogs, on the Magna Carta and 800 years of Elected Mayors, which I really had totally forgotten. Whereupon I realised too that I couldn’t actually recall much of what Catherine, I and other colleagues contributed to that decade of debate on elected mayoral evolution.

So, the remainder, the structure, and – I fear – the length of this blog were prompted, yes, by much of the media coverage of this month’s elections, and the sense that the spread and substance of mayoral government over the past decade aren’t fully recognised even by those who supposedly follow these things; and also by the notion that it would be a pleasing mini-tribute to Catherine to do so by identifying and italicising particularly some of her and colleagues’ INLOGOV blog contributions on these mayoral matters over the years.

We start, however, for the benefit of comparatively late arrivals, at the beginning of not the blog, but the concept. Mayoral government is a postulation you might expect to have found a supportive, even enthusiastic, reception in an Institute of Local Government Studies and it mainly did, albeit with perhaps a certain reservation. Directly elected mayors (DEMs) had played a fluctuating role in the Blair Government’s local government agenda from the outset. London, noted in Labour’s 1997 manifesto as “the only Western capital without an elected city government”, would have a “new deal”. Which took the form in 2000 of the creation of the Mayor-led Greater London Authority – in the manifesto, so no referendum required. Probably no reminder required either, but they’ve been: Ken Livingstone (Ind/Lab; 2000-08), Boris Johnson (Con; 2008-16); Sadiq Khan (Lab; 2016- ).

The Local Government Act 2000 then provided all English and Welsh councils with optional alternatives to the traditional committee system. Chiefly, following a petition of more than 5% of their electorate, they could hold a referendum on whether to introduce a directly elected mayor plus cabinet. There were 30 of these referendums in 2001/02, producing 11 DEMs – plus Stoke-on-Trent’s short-lived mayor-plus-committee system – three in London boroughs, but most famously Hartlepool United’s football mascot, H’Angus the Monkey, aka Stuart Drummond (Indep).

Ten referendums over the ensuing decade produced a further three mayors, prompting the now Cameron-led Conservatives to pledge in their 2010 manifesto to introduce elected ‘Boris-style’ mayors for England’s 12 (eventually 11) largest cities, with significant responsibilities including control of rail and bus services, and money to invest in high-speed broadband.

These DEM referendums eventually took place in May 2012 – three months after the launch of the INLOGOV blog – and provided a natural topic for early blogs by Catherine and colleagues (Ian Briggs). The referendums followed protracted Whitehall battles over mayoral powers (CG) – as revealed by the then Lord Heseltine in a UoB Mayoral Debate (CG) – a combination of ministerial indecision and interference (CG) against a backdrop of opposition from most of the respective councils’ leaderships, with Bristol the only one of the 12 cities voting even narrowly in favour (Thom Oliver).

Birmingham voted 58% against, despite Labour’s having in Liam Byrne a candidate raring to go, and Coventry 64% against. There was speculation over whether the addition of a well publicised mayoral recall provision (CG) might have swung some of the lost referendums. But it was what it looked: an overdue, and to some welcome (Andrew Coulson), end of an episode (Karin Bottom);arguably “the wrong solution to the wrong problem” (Catherine Durose).

Since then, the referendums successfully removing elected mayors (Stoke-on-Trent, Hartlepool, Torbay, Bristol) have exceeded those creating new ones (Copeland, Croydon) – though, in fairness, those four removals were more than matched by five retention votes.

A ‘mayoral map’ at the end of that first decade would have looked something like the inset in my illustration of in fact the first 20 years of referendum results – numerous splotches of red for Reject, a few smaller green specks for Accept, and overall a patchy, somewhat arbitrary, experiment that on a national scale never really took off.

The mayoral concept, though, had also generated interest outside local government – the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), for instance, advocating Mayors for Greater Manchester, the West Midlands, and Liverpool City Region to take the required ‘big’ decisions on housing, transport, and regional development. Prime Minister David Cameron too was a ‘city mayors’ fan, although what scale of ‘city’ wasn’t initially clear, until in 2014 what became known as the first ‘devolution deal’ (Catherine Needham) was announced with the Greater Manchester Combined Authority. Headed by an elected ‘metro-mayor’ (CG), comparable to the Mayor of London, the GMCA would have greater control over local transport, housing, skills and healthcare, with “the levers you need to grow your local economy”.

New legislation – the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016 – was required, allowing the introduction of directly elected Mayoral Combined Authority or ‘Metro Mayors’ (Vivien Lowndes & Phil Swann) (+ Catherine Staite) in England and Wales, with devolved housing, transport, planning and policing powers.

The Combined Authority elections were held in May 2017 – not coinciding with the General Election (CG) as PM Theresa May had contemplated but, in contrast to Rishi Sunak, chickened out of – with perhaps usefully split results (CG). Elected were Andy Burnham (Lab, Greater Manchester), Steve Rotheram (Lab, Liverpool City Region), Ben Houchen (Cons, Tees Valley), Andy Street (Cons, West Midlands), Tim Bowles (Cons, West of England), and James Palmer (Cons, Cambridgeshire & Peterborough) – followed in 2018 by Dan Jarvis (Lab, Sheffield City Region). The map had started to change – even within the first hundred days (CG) – stutteringly under the less committed Theresa May and/or in several cases where groups of local authorities failed to agree – but eventually dramatically, as evidenced in the larger illustrated map. The Staite/Lowther ‘Briefing Paper’ was well timed.

A few years on, mayoral devolution has trailblazed across the country (CG) to a greater extent than even some commentators on this year’s local elections seemed to have difficulty grasping. As of March 2024, devolution deals had been agreed with 22 areas, covering 60% of the English population – most recently, in late 2022, North of Tyne, Norfolk/Suffolk, East Midlands, York & North Yorkshire; in 2023 Cornwall, Greater Manchester and West Midlands (‘Trailblazers’), Greater Lincolnshire, Lancashire, Hull/East Yorkshire; and so far in 2024 Buckinghamshire, Warwickshire and Surrey.

From next year, if you draw a straightish line from, say, Ipswich in South Suffolk up through about Alvechurch in South Birmingham, heading for Shrewsbury, at least five-sixths of the bits of England to your north will be under mayoral devolution. Which, to me anyway, seems pretty dramatic news, and considerably more interesting than the endless General Election Date speculation that passed this May for ‘Local Elections’ reporting.

Picture credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayor_Quimby

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.