Prof. Catherine Staite and Jason Lowther

In this long-read, INLOGOV’s Professor Catherine Staite and Jason Lowther provide an in-depth brief on the role of the new elected mayors, how they relate to the devolution agenda and the things we should watch out for ahead of the upcoming mayoral elections on May 4th.

1. Introduction

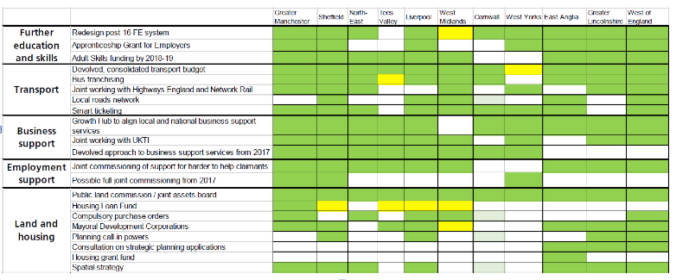

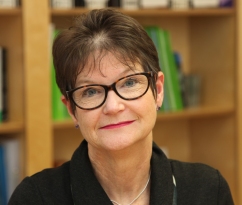

The role of elected mayor for regions, such as the West Midlands and Greater Manchester, has been created as part of a move to greater devolution of power over resources and policy, from central government to consortia of local authorities known as Combined Authorities, through which individual authorities have agreed to collaborate in applying these new powers and resources. The Combined Authorities have negotiated individual ‘devo deals’ with central government and, as a result, the extent of their devolved powers varies enormously (see Table 1 below). For example, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, formed in 2011, has been granted the most extensive powers of any Combined Authority, including powers over the NHS in the GM region. One of the prerequisites of the devolution of significant powers and resources to Combined Authorities has been the creation of a new elected office – that of a directly elected regional mayor.

Table 1: Powers to Devolved in Devolution Deals.

Of course, mayors are nothing new. Joseph Chamberlain, who led the foundation of this University, was elected Mayor of Birmingham in 1874 and acted as catalyst for hugely significant improvements to the lives of the people of Birmingham in the 1870’s and 80’s; clean water, better pavements and roads, as well as the iconic municipal buildings which still give the city its distinctive character today. District, Borough and City Councils across the country already have civic mayors, who are appointed from among the council members, not directly elected by the public. They are easily identified, when carrying out their largely ceremonial roles, by their robes and chains of office. More recently, directly elected “executive” mayors have been created in some local councils.

The question about whether we should have more elected mayors has been hotly contested. Conservative governments have demonstrated a surprisingly enduring enthusiasm for elected mayors for many years, in the face of opposition from many of their own MPs, local politicians of all political hues and the demonstrable apathy and mistrust of the public.

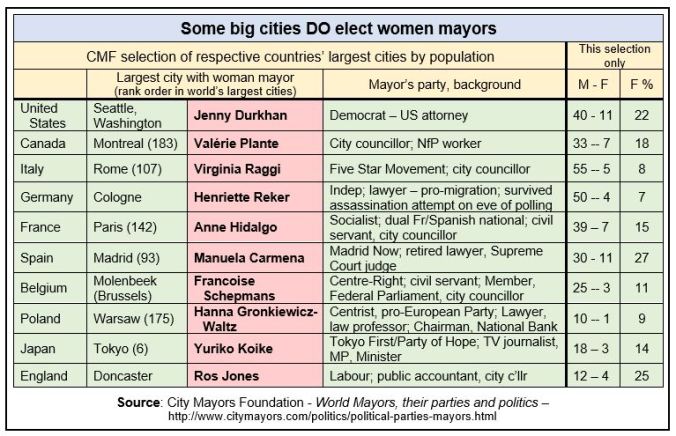

2. What can we learn from international comparisons?

There is an international trend towards directly elected mayors, especially in cities. The number of countries and cities that have decided to introduce directly-elected mayors has increased markedly since the 1980s (Hambleton and Sweeting, 2014). In Europe, directly elected mayors were introduced into systems of local government in Slovakia (1990), Italy (1993), Germany, Hungary (1998), the UK (2000) and Poland (2002).

Outside Europe directly-elected mayors are now in place in many countries including New Zealand.

Hambleton and Sweeting (2014) suggest the mayoral trend is linked to four key themes in urban leadership:

- The institutional design of local government: the attempt to enable effective civic leadership.

- The drive for outward-facing leadership: responding to the trends of global competition and the need for “networked” governance where local authorities work with other statutory and non-statutory providers in multi-agency partnerships to deliver social policy.

- The changing relationships between politicians and officers: including issues around the potential politicisation of the bureaucracy.

- The relationships between city leaders and followers: with direct election challenging traditional party political models.

Hambleton and Sweeting (2015) summarise the arguments for and against directly elected mayors. Arguments in favour of directly elected mayors include:

- Visibility – citizens and others know who the leader of the city is, generating

- Interest in public issues

- Legitimacy and accountability – arising from the direct election process

- Strategic focus and authority to decide – a mayor can make tough decisions for a city and then be held to account

- Stable leadership – a mayor typically holds office for four years and this can underpin a consistent approach to government

- Potential to attract new people into politics – creative individuals may be able to stimulate innovation in citizen activism and business support

- Partnership working – a mayor is seen as the leader of the place, rather than the leader of the council. This can assist in building coalitions

The arguments they present against directly elected mayors are:

- A concentration of power – the model could place too much power in the hands of one person, who is overloaded

- Weak power of recall – elect an incompetent mayor and the city is stuck with this person for four years

- Celebrity posturing – the model could attract candidates more interested in self-promotion than sound policy-making

- Wrong area – the Localism Act 2011 provided for mayors to be elected for unitary authorities when many consider that metropolitan mayors, covering a number of unitary areas, on the London model are needed

- Cost – having a mayor will cost more money if the rest of the governance architecture of an area is unchanged

- Our over-centralised state remains – without a massive increase in local power to decide things, the mayor will be a puppet dancing on strings controlled in Whitehall

Gains (2015) suggests that the current weak engagement between electors and representatives argues for a more visible and accountable leadership. She argues that calls for more participation require an activist leadership reaching out to citizens and bypassing entrenched interests such as political parties.

The Warwick Commission on “Elected Mayors and City Leadership” argued that “directly elected mayors offer the possibility of greater visibility, accountability and co-ordinating leadership as well as re-enchanting the body politic, and much of this derives from their relative independence from party discipline through their direct mandate and through their four year term. But they also hold the dangers of electing mayors whose popularity obscures their inadequacy in leading their communities” (Warwick Commission, 2012:7).

They pointed to five reasons often cited for the rise of the elected mayor as follows:

- A response to the rise of the network society that otherwise disperses responsibility and a demand for greater accountability from political leaders

- An attempt to reinvigorate democratic politics and civic engagement in the face of apparently widespread political apathy

- A localist and decentralising reaction against the rise of the centralising power of the state or super state (European Union)

- The realisation by some local politicians in certain areas that they can make the most impact through elected mayors, not traditional party politics

- The return of ‘personality’ to the political agenda in place of depersonalised party systems.

International case studies

- Directly elected mayors since 1993.

- Mayor appoints executive including non-councillors (often during the election campaign).

- Limited to 2 consecutive terms.

- Wide executive powers including roads, education, social services, housing, social security, planning, police, transport.

- Mayor “acts as a powerful focus point of political decision making and is able to speak to all tiers of Italian government as a legitimate political leader and ambassador for the area. Indeed, mayors are often important players in the distribution of national resources to the localities” (Copus, Leading the Localities, 2006:145)

- Council can either approve Mayor’s programme or table “no confidence motion” which results in resignation of both the Mayor and the council.

- “Strong” mayors predominate in larger cities, directly elected with mayor-council form of government (“weak” mayoral model in smaller towns with mayor indirectly elected by council).

- Mayor acts as chief executive officer, directs administrative structure, sets policy agenda for the city, determines the details of the budget, and has a veto over council decisions (though may be over-ridden by two-thirds council vote).

- New York City Mayor elected for maximum of three 4-year terms. The Council is a “deliberative and investigative body” monitoring performance, making land use decisions and passing local legislation.

3. How widespread are elected mayors in the UK?

The first directly elected mayor in the UK was introduced in Greater London in 2000 as part of the statutory provisions of the Greater London Authority Act 1999.

In England, elected mayors were established by the Local Government Act 2000. Eleven councils adopted a mayoral system (3% of councils), with over 80% adopting the leader-cabinet system.

As of May 2016, there had been 52 referendums on the question of changing executive arrangements to a model with an elected mayor. Of these, 16 have resulted in the establishment of a new mayoralty and 36 have been rejected by voters. The average “yes” vote was 45%. Typical turnout was around 30%, varying from 10% to 64%. There have been six referendums on the question of removing the post of elected mayor, of which three have been disestablished.

The Localism Act 2011 permitted central government to trigger referendums for elected mayors in 10 large English cities. On 3 May 2012, referendums were held in these cities to decide whether or not to switch to a system that includes a directly elected mayor. Only one, Bristol, voted for a mayoral system.

In 2014 it was announced that a Mayor of Greater Manchester will be created as leader of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority. From 2017 onwards there are expected to be directly elected mayors for Greater Manchester, the Liverpool City Region, the West Midlands, and Tees Valley as part of the devolution deals introduced by the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016.

3.1 UK case studies

Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester (GM) has a long history of cross authority working and infrastructure. In 2011 they became the first group of authorities to establish a combined authority. Recently GM has been granted devolved decision-making which is (in UK terms) remarkably extensive. The “price” of this has been to agree to the imposition of a “metro mayor”.

The GM mayor will have devolved powers around housing, transport and (subject to unanimous approval by the constituent councils) spatial planning. They will also become the Police and Crime Commissioner for GM. They will chair the GM Combined Authority (GMCA).

GMCA will have responsibilities around devolved business support, further education, skills and employment, and housing investment. It will jointly commission (with DWP) the next stage of the Work Programme, and has recently taken on responsibilities around health and social care integration.

In GM, the mayor’s decisions can be rejected by two-thirds of the cabinet consisting of the leaders of the ten constituent councils. The Statutory Spatial Framework is subject to unanimous agreement by this cabinet.

The new elected mayor will be subject to scrutiny by the existing scrutiny committee of the GMCA: the ‘GMCA Scrutiny Pool’, made up of 30 non-executive councillors drawn from the ten Greater Manchester boroughs.

The Government passed an amending Order to create an eleventh member of the GMCA (alongside the ten borough leaders) to be the ‘interim mayor’ until the first mayoral election. Tony Lloyd, Greater Manchester Police and Crime Commissioner, was appointed to the post (by the existing members of the GMCA) on 29 May 2015.

The March 2016 Budget announced the following additional powers for the GMCA:

- bringing together work on Troubled Families, Working Well, and the Life Chances Fund into a single Life Chances Investment Fund;

- working with the Government and PCC on joint commissioning of offender management services, youth justice and services for youth offenders, the courts and prisons estates, ‘sobriety tagging’, and custody budgets;

- taking on adult skills funding

- further discussion over approaches to social housing.

The 2016 Autumn Statement further announced devolution of the budget for the forthcoming national Work and Health Programme and the beginning of talks on future transport funding in Greater Manchester.

West Midlands

The West Midlands mayor will represent a population of over 2.8 million people, compared to the average MP parliamentary constituency of under 96,000 people – almost 30 times as significant. The powers of the elected mayor are not yet proportionately significant.(see https://westmidlandscombinedauthority.org.uk/media/1572/adocpackpublicversion0001.pdf)

The West Midlands mayor will have limited independent powers, mostly relying on building consensus with local council leaders.

The constitution of the WMCA was approved on 10th June 2016 and published here:

https://westmidlandscombinedauthority.org.uk/media/1171/ca-draft-constitution-24-5-16.pdf

The constitution suggests that “any matters that are to be decided by the Combined Authority are to be decided by consensus of the Members where possible”. Where consensus is not achieved, each Member is to have one vote and no Member including the Chair is to have a casting vote.

Usually votes will require a two-third majority of constituent members, however several areas required a unanimous vote of all members, including:

- approval of land use plans;

- financial matters which may have significant implications on Constituent Authorities’ budgets;

- agreement of functions conferred to the Combined Authority;

- use of general power of competence within the Local Democracy Economic Development and Construction Act 2009, including in relation to spatial strategy, housing numbers and the exercise of any compulsory purchase powers;

- approval to seek such other powers

- changes to transport matters undertaken by the Combined Authority.

Non-constituent members will be able to vote on defined issues (where a simple majority is required) including around:

- adoption of growth plan and investment strategy and allocation of funding by the Combined Authority

- the super Strategic Economic Plan strategy along with its implementation plans and associated investment activity

- the grant of further powers from central government and/or local public bodies that impacts on the area of a Non Constituent Authority

- land and/or spatial activity undertaken by the Combined Authority within the area of a Non-Constituent Authority

- Public Service reform which affects the areas of Non-Constituent Authorities

- all Combined Authority matters concerned with education, employment and skills, enterprise and business support, access to finance, inward investment, business regulation, innovation, transport, environmental sustainability, housing, economic intelligence, digital connectivity and regeneration

- future use of business rate retention funding generated beyond that retained within new and existing Enterprise Zones

The WMCA “cabinet” (council leaders) will examine the Mayor’s draft annual budget and the plans, policies and strategies, as determined by the Mayoral WMCA, and will be able to reject them if two-thirds of the Mayoral WMCA Cabinet agree to do so. In the event that the Mayoral WMCA reject the proposed budget then the Mayoral WMCA shall propose an alternative budget for acceptance by the Cabinet, subject to a two-thirds majority of those present and voting. The Mayor shall not be entitled to vote on the alternative Mayoral WMCA proposed budget. In terms of specific functions:

- “Mayoral functions” will be devolved to the Mayoral WMCA by central government, exercised by the Mayor and subject to the provisions in the Scheme.

- “Mayoral WMCA/Mayoral joint functions” are subject to the Mayor’s vote being included in the majority in favour with the two-thirds of the Constituent Members voting.

- Mayoral “WMCA functions” are not subject to the Mayor’s vote being included in the majority in favour with the two-thirds of the Constituent Member voting. The items reserved for unanimous voting of the Constituent Members are also not subject to the Mayor’s vote in favour.

The functions which are proposed to be “Mayoral functions” are:

- HCA CPO powers (with the consent of the appropriate authority(ies)

- Grants to Bus Service Operators

- Devolved, consolidated transport budget

- Reporting on the Key Route Network (in consultation with the authorities)

- Mayoral precept

- Raising of a business rate supplement (in agreement with the relevant LEP Board(s) and the Mayoral WMCA)

- Functional power of competence (but no general power of competence).

4 How do mayors fit with the wider devolution agenda?

The Government’s approach to devolution has been to negotiate the transfer of powers through a series of “devolution deals” or agreements. The House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee concluded that “the Government’s approach to devolution in practice has lacked rigour as to process: there are no clear, measurable objectives for devolution, the timetable is rushed and efforts are not being made to inject openness or transparency into the deal negotiations” (CLG Committee, 2016).

The 2015 devolution agreements are a development of a series of “city deals” between 2011 and 2015; first with the eight core cities and later with 20 smaller cities and city regions.

The devolution deals agreed so far have many similarities in terms of powers to be devolved (Sandford, 2016). The core powers devolved include the following:

- Restructuring the further education system. Some areas will also take on the Apprenticeship Grant for Employers.

- Business support. In most areas, local and central business support services will be united in a ‘growth hub’.

- The Work Programme. This was the Government’s main welfare-to-work programme, subsequently replaced by a much smaller Work and Health programme. Many areas are to jointly develop a programme for ‘harder-to-help’ benefit claimants.

- EU structural funds. A number of areas are to become ‘intermediate bodies’, which means that they, instead of the Government, will be able to take decisions about which public and private bodies to give EU structural funds to. The future of these funds is of course in doubt following the EU referendum.

- Fiscal powers. Many deals include an investment fund, often of £30 million per year. Elected mayors will have the power to add a supplement of up to 2p on business rates, with the agreement of the relevant Local Enterprise Partnership.

- Integrated transport systems. Many deals include the power to introduce bus franchising, which would allow local areas to determine their bus route networks and to let franchises to private bus companies for operating services on those networks. Each deal also includes a unified multi-year transport investment budget.

- Planning and land use. Many deals include the power to create a spatial plan for the area.

Further details are provided in the Annex to this paper.

5 How well have other elected mayors performed?

Mayors in England have had a mixed picture of performance. In Stoke and Doncaster they did not deliver improvement, but in some areas they are linked to significant progress. The Warwick Commission concluded “our evidence suggests that elected mayors offer a real opportunity for change in a place where change is needed and also a way of invigorating a body politic”.

Gains (2015) concludes that “the evidence base for improved performance under mayoral governance is weak”. However, reviewing evidence on the introduction of the first city mayors she notes that “compared to areas operating a leader/cabinet model where the leader was indirectly elected, respondents to surveys of councillors, officer and local stakeholders in mayoral authorities agreed more strongly that there was quicker decision-making, that the mayor had a higher public profile, that decision-making was more transparent, that the council was better at dealing with cross cutting issues that relationships with partners improved and disagreed more strongly with the statement that political parties dominated decision-making”.

The Bristol Civic Leadership Project has explored the question “What difference does a directly-elected mayor make?” since September 2012. An early analysis published in 2014 identified that the Mayor had enjoyed access to central government ministers, that he had emphasised leading the city rather than the council, and that he was a more prominent public figure in Bristol city life than any previous leader.

The project’s final report in Sept 2015 (Hambleton and Sweeting, 2015) concluded that there has been a changed perception of governance in Bristol, in particular:

- Many perceive an improvement in the leadership of the city, in areas such as the visibility of leadership, there being a vision for the city, the representation of Bristol, and leadership being more influential than previously was the case.

- However, there are areas where the model is seen as performing inadequately. There are concerns about the levels of representation of views within the city, trust in the system of decision-making, and the timeliness of decision-making.

- Frequently there are considerable differences of view about the mayoral model of governance from those situated in the different realms of civic leadership in Bristol. Councillors tend to display considerably more negative views about the impacts and performance of the new model compared to those in public managerial, professional, community and business realms.

- Members of the public in different parts of Bristol tend to think somewhat differently about the impacts of the reform. Often, but not universally, those people living in better off parts of Bristol are inclined to see the move to, and the impacts of, the mayoral model more positively than those living in less well off parts of Bristol.

Assessments of the impact of the London Mayor are complicated by the evolving powers linked to this role. The initial model was largely restricted to transport, and led to the successful introduction of the congestion charge and cycling initiatives. The subsequent successful bid for the London Olympics 2012 perhaps demonstrates the wider “power” of the role.

Analysis suggests that leadership turnover in places with mayors is 50% lower than those with council leaders (Warwick Commission, 2012:29).

6 What issues remain to be resolved?

6.1 Scrutiny, checks and balances

The Warwick Commission argued that the relationship between mayor and full council needs to be constructed so the mayor is visibly held to account, yet their mandate should not be undermined by a body which has been separately elected. There needs to be an appropriate recall process which enables the removal of an elected mayor in office in extremis.

Gains (2015) argues that democratic considerations initially received insufficient attention in Greater Manchester. These relied on the cabinet of local council leaders provided strong veto powers and the four-yearly direct election of the mayor. However, she points out that the potential for wider and innovative public engagement and effective formal scrutiny were not fully explored initially. The latter could not rely on the cabinet because “their executive role precludes the kind of independent scrutiny expected elsewhere in local government”. She points out the more active public engagement and transparency arrangements are now being developed in GM.

The CLG Select Committee review of Devolution Agreements found “a significant lack of public consultation and engagement at all stages in the devolution process” (CLG Select Committee, 2016)

The Cities and Local Government Devolution Bill 2016 sets out key requirements for overview and scrutiny arrangements. Each combined authority will be required to establish at least one overview and scrutiny committee, consisting of backbench councillors from the constituent councils, to review and scrutinise its decisions and actions and those of the elected mayor.

Alternative models have been suggested through local decisions on a clear governance framework (Centre for Public Scrutiny) or introducing “second chambers” of people from the business, voluntary and community sectors and citizens’ panels (Institute for Public Policy Research North).

6.2 Public engagement and consultation

A number of criticisms have been made of the lack of public consultation in most devolution negotiations. The House of Commons Local Government Select Committee found “a significant lack of public consultation and engagement at all stages of the devolution process” (CLG Committee, 2016).

There have been some examples of innovative engagement, for example the University of Sheffield and the Electoral Reform Society, with other partners, held two “citizens’ assemblies” in autumn 2015, in Sheffield and Southampton. Over two weekends, invited members of the public discussed devolution options in their local areas. Details of the assemblies and the outcomes of the public discussions can be found at http://citizensassembly.co.uk/. Similarly, Coventry held a one-day citizens’ panel on 9 September 2015, discussing whether the city should participate in the West Midlands combined authority. (Sandford, 2016).

6.3 Mayoral Powers

The Warwick Commission stressed that “the difference between ‘powers’ and ‘power’ is critical in discussing elected mayors. Whilst the debate about clarity over which powers (and budgets) Whitehall will hand to cities with directly elected mayors will continue, it is also important to recognise the soft and invisible power that has often been accumulated by elected mayors that sits outside their statutory remits has been considerable. In many cases, it has led to the granting of more powers” (Warwick Commission, 2012:8).

That said, they argue that “Mayors should examine the totality of the public spend in a place and hold bodies over which they do not have budgetary control to public account in a wider sense, e.g. the combined impact of social care, recidivism amongst low level offenders, impact of welfare and work and training”.

In terms of the national legislative framework, many powers are now available to elected Mayors. The list in Table 1 (below) is taken from NLGN’s publication “New Model Mayors: Democracy, Devolution and Direction” (2010) updated for powers subsequently provided to elected mayors.

Table 1: Comparison of current mayoral powers with NLGN proposals

| NLGN Proposal |

Current position |

| The financial flexibility to balance budget over the 3 final years of a term, instead of being limited by in-year balancing |

No |

| The creation of a single capital investment pot for the area, so that all relevant monies are pooled and control over spend maintained by the mayor |

Yes? |

| The power to introduce a supplementary business rate of up to + or – 4p, with any extra funds raised to be spent on economic development within the locality as deemed best by the mayor |

Partly – currently limited to 2p and subject to agreement with the local business-led LEP. |

| Permission to use TIF mechanism through the establishment of an ADZ |

Yes (through New Development Deals) |

| Ability for mayor to appoint or dismiss Chief Executive, giving the council an advisory role but the final decision to rest with the Mayor |

No |

| Similar transport powers to those that the Mayor of London currently enjoys, in particular to have a say in local transport provision within the authority’s boundaries through chairing (or the nomination of chair) of the local transport body |

Yes? |

| The introduction of a new post of Police Commissioner, with the Mayor taking up this position or appointing a councillor to this position |

Yes |

| The power of appointment for the position of PCT Chief Executive and in addition power to nominate one person to sit as a non-executive member on the board of the PCT |

No |

| Alignment of PCT priorities with local Mayoral health priorities |

GM only |

| Responsibility, powers and funding for 14-19 and adult skills |

Yes |

| The formation of a statutory Employment and Skills Board, chaired by the Mayor or a representative of the Mayor, to devise strategy |

Yes? |

| Fast-tracked to a devolved commissioning model for welfare-to-work provision |

No – DWP resist devolved commissioning but promise to engage with local areas. |

| A seat in the second chamber of the Houses of Parliament |

No

|

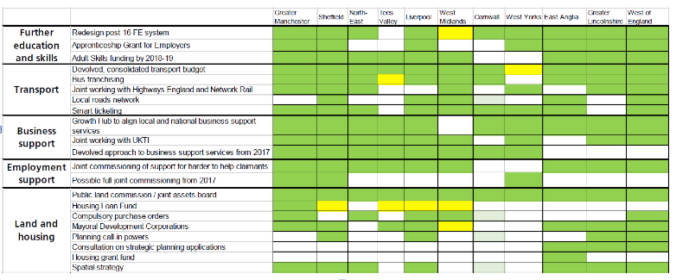

6.4 Gender balance

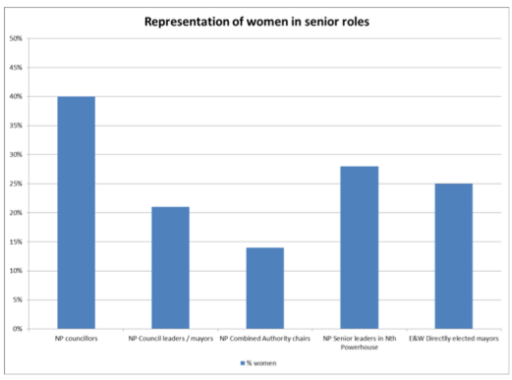

Recent research by the Fawcett Society (Trenow and Olchawski, 2016) concludes that the current approach to devolution “risks handing power to male-dominated structures and shutting women out of the decision making process”.

Their analysis shows that for the Northern Powerhouse area (NP in the chart), 40% of councillors are women, rising to 50% in Manchester City Council. In this respect they outperform Westminster, where only 29% of MPs are women, and Police and Crime Commissioners (16% women).

Diagram 1: Representation of women

However, the proportion of women falls significantly when considering senior positions in the Northern Powerhouse. For these roles the figures are: to 28% of senior leadership roles and 14% of chairs of established and proposed combined authorities. More generally, so far only four out of 16 existing directly elected mayors in England are women.

References

CLG Select Committee, Devolution: the next five years and beyond, First Report of Session 2015–16, January 2016.

Gains, Francesca. “Metro mayors: devolution, democracy and the importance of getting the ‘Devo Manc’ design right.” Representation 51.4 (2015): 425-437.

Hambleton, Robin, and David Sweeting. “Innovation in urban political leadership. Reflections on the introduction of a directly-elected mayor in Bristol, UK.” Public Money & Management 34.5 (2014): 315-322.

Hambleton, Robin, and David Sweeting. “The impacts of mayoral governance in Bristol.” (2015).

Osborne, “Chancellor on building a Northern Powerhouse”, HM Treasury and The Rt Hon George Osborne MP, 14 May 2015

Sandford, Devolution to local government in England, House of Commons Library briefing paper number 07029, 5 April 2016

Svara, James H. Official leadership in the city: Patterns of conflict and cooperation. Oxford University Press on Demand, 1990.

Trenow, Polly and Jemima Olchawski, The Northern Powerhouse: an analysis of women’s representation, Fawcett Society, 2016

Warwick Commission. “Elected mayors and city leadership summary report of the Third

Warwick Commission.” Warwick, Warwick University (2012).

As Directo r of Public Service Reform, Professor Catherine Staite leads the University’s work supporting the transformation and reform of public services, with a particular focus on the West Midlands. Her role is to help support creative thinking, innovation and improvement in local government and the wider public sector. As a member of INLOGOV, Catherine leads our on-line and blended programmes, Catherine teaches leadership, people management, collaborative strategy and strategic commissioning to Masters’ level. Her research interests include Combined Authorities, collaboration between local authorities and the skills and capacities which elected members will need to meet the challenges of the future

r of Public Service Reform, Professor Catherine Staite leads the University’s work supporting the transformation and reform of public services, with a particular focus on the West Midlands. Her role is to help support creative thinking, innovation and improvement in local government and the wider public sector. As a member of INLOGOV, Catherine leads our on-line and blended programmes, Catherine teaches leadership, people management, collaborative strategy and strategic commissioning to Masters’ level. Her research interests include Combined Authorities, collaboration between local authorities and the skills and capacities which elected members will need to meet the challenges of the future

Jason Lowther is a senior fellow at INLOGOV. His research focuses on public service reform and the use of “evidence” by public agencies. Previously he led Birmingham City Council’s corporate strategy function, worked for the Audit Commission as national value for money lead, for HSBC in credit and risk management, and for the Metropolitan Police as an internal management consultant. He tweets as @jasonlowther

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

r of Public Service Reform, Professor Catherine Staite leads the University’s work supporting the transformation and reform of public services, with a particular focus on the West Midlands. Her role is to help support creative thinking, innovation and improvement in local government and the wider public sector. As a member of INLOGOV, Catherine leads our on-line and blended programmes, Catherine teaches leadership, people management, collaborative strategy and strategic commissioning to Masters’ level. Her research interests include Combined Authorities, collaboration between local authorities and the skills and capacities which elected members will need to meet the challenges of the future

r of Public Service Reform, Professor Catherine Staite leads the University’s work supporting the transformation and reform of public services, with a particular focus on the West Midlands. Her role is to help support creative thinking, innovation and improvement in local government and the wider public sector. As a member of INLOGOV, Catherine leads our on-line and blended programmes, Catherine teaches leadership, people management, collaborative strategy and strategic commissioning to Masters’ level. Her research interests include Combined Authorities, collaboration between local authorities and the skills and capacities which elected members will need to meet the challenges of the future