Chris Game

I chanced recently upon, in the LocalGov news circular, a local elections preview by Jonathan Werran, CE of the cross-party think tank Localis, which mentioned, in the guise of a rhetorical question, the Birmingham Post.

“When the Birmingham Post’s circulation is less than a thousand copies for what is England’s second city, is this sufficient evidence that there is no audience at all for local politics … that this apathy mirrors widespread public indifference for local government accountability and scrutiny, and the sense that local services are something ‘done to’ residents and communities rather than for or with them?”

The remainder of the piece bypassed, rather than refuted, that accusation, en route to vigorously asserting that, even if ministers and civil servants are the key policy shapers, they do their shaping with the knowledge of what happens at the local ballot box.

As a longstanding INLOGOV member with a particular interest in local elections, I wince when politicians or commentators almost dismissively describe any local election year as low-key. It signals that they’ll continue endlessly pontificating about ‘the big one’ in July, November or whenever, while ignoring the thousands of contests and hundreds of local policy issues at stake on May 2nd – AND that this time at least they’re demonstrably wrong.

Which is what I’ve devoted 2,000+ words in, as it happens, this week’s Birmingham Post, to arguing that for us Metropolitan West Midlands electors, every one with two or three separate votes to bestow or withhold – or, indeed, the 150,000-plus full- and part-time staff photo ID-checking in some 40,000 polling stations – next Thursday in actuality is as big as it gets.

OK, I’m guessing a bit about those latter numbers, but the rest holds. This year, almost unprecedentedly (except for the 2021 post-Covid elections), every part of England and Wales[1] has at least one ‘local’ or sub-national, election – local council, mayoral, London Assembly, Police & Crime Commissioners. And, whatever happens in the General Election, the winners will still be there, representing and working for their respective communities, come 2025.

The best illustration of all this is through the Local Government Information Unit (LGIU)’s set of interactive maps – available online, uncontemplatable for the Birmingham Post,but deployable here.

MAP 1 shows LOCAL COUNCIL ELECTIONS, and indeed occupying this year perhaps about an eighth of the England part of the map – as this is a ‘non-county’ year, with no Welsh council elections.

In our still substantially ‘two-tier’ county-district local government system, next Thursday’s elections are for the minority of English district and unitary councils who elect their councillors by thirds or halves, rather than all-out, and for mainly single-tier metropolitan boroughs – smallish in map-area, but with big, concentrated populations, and most of which (Birmingham is an exception) still elect a third of their councillors in three years of each four-year cycle.

Their sizable urban electorates are clustered into small areas of the map, particularly in Yorkshire/Lancashire, and currently are very clustered politically too. Of the three dozen-plus mainly metropolitan councils north of about Cannock Chase with upcoming elections, just one – North East Lincolnshire – is currently Conservative.

The stand-out patch of Conservative blue in the south is Dorset. Established in 2019, its councillors, uniquely and for unexplained reasons, were elected for five-year terms of office, which are replicated this year. There are several blue blobs in our West Midlands metropolitan region – Dudley, Solihull and Walsall – but gone are the days when they can be assumed naturally and nationally to outnumber the Lib Dems’ yellowy-orange. And the black-coloured councils under ‘No Overall Control’ by any single party comfortably outnumber both.

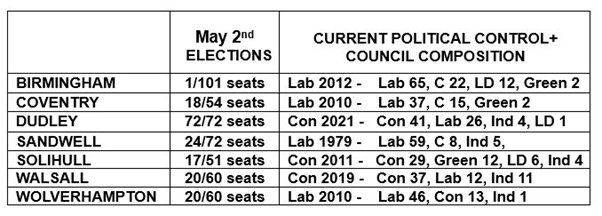

The statistical details of the West Midlands metropolitan contests are summarised in the following abbreviated version of the table included in my Post article.

The LGIU’s MAP 2 shows COMBINED AUTHORITY (CA) MAYORAL ELECTIONS – those areas created in relatively recent years allowing groups of upper-tier councils to pool responsibility for delivering functions devolved from central government, like transport, economic policy and regeneration, more effectively over a wider area, in our case the West Midlands.

With the formal establishment of the North East CA, there will be 11 of these Combined and Combined County Authorities, our West Midlands CA being one of the longer established, and nine, including us, will be electing or re-electing their Mayors. It is no exaggeration to suggest that, of all the 2,700-plus elections, this West MIdlands one can be considered the single most important – for our city’s future, but also for the future direction and vibrancy of the whole country’s sub-central government.

This LGIU map has just two modest-sized patches of Conservative blue: Tees Valley, whose elected Mayor since 2017 has been Ben Houchen – The Lord Houchen of High Leven to you and me – and the West Midlands led by Andy Street. We know how tight our contest will be – a single Savanta poll managing to put Street both two points ahead of Labour candidate Richard Parker, then three points behind! – and, if both CAs were to swing to Labour, it would surely raise questions for the next Government about the future of this crucial strand of devolution.

Which brings us to the LGIU’s Map 3 – the POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER ELECTIONS – in England an almost uninterrupted mass of Conservative blue, with patches of Labour red, and, dominating mid-Wales, a substantial block of Plaid Cymru green. Being picky, I’d add a red patch for the Labour Mayor of London, as he (Sadiq Khan) is London’s equivalent of a PCC and both he and the London Assembly should properly be included somewhere on the maps.

It is, of course, these 41 PCC elections, covering all England and Wales, which give May 2nd its indisputably national dimension – and also brought the West Midlands its first election-related headlines. PCCs were created in 2011/12 to make police forces more visibly responsive to local needs. Their core functions are to appoint the chief constable, set the budget, and set local policing priorities, subsequently extended in some cases (like Staffordshire) to the local fire and rescue service.

However, as Mayor Andy Street has long been somewhat enviously aware, his fellow (Labour) Mayors of Greater Manchester (Andy Burnham) and West Yorkshire (Tracy Brabin) had both acquired PCC functions, so why shouldn’t he have a second go at grabbing some of that action.

It’s a challenge – or attempted “hostile takeover” – that, had he acted much earlier and more strategically, could have prompted a useful public cost-benefit debate about the value of having a separate elected PCC role. Certainly, the bid should have been thoroughly researched and publicly tested. But in their partisan eagerness it seems either Mayor Street, or the Home Office on his behalf, screwed up.

West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner Simon Foster (Lab) was able to claim that the Conservative Home Secretary had a “closed mind” on the issue, and the Judge found that exactly how the change would lead to a more joined-up approach to crime prevention was “left entirely unexplained”. Simon Foster, naturally, is standing for re-election as PCC, but challenged this time by just the single Conservative & Unionist candidate, Tom Byrne, rather than the previous six..

As has been extensively noted, Mayor Street’s campaign generally excludes reference to the Conservative Party, if not from the ballot paper, from his campaign material and social media accounts. His is an individual ‘Brand Andy’ campaign, he explains, and “people are sick and tired of Westminster”. And, of course, of his party – as he didn’t add.

I’ve not seen the point made explicitly, but ‘Brand Andy’ could apply even more strikingly to our Mayor’s evidently genuinely warm and productive working relationship with Greater Manchester Mayor, Andy Burnham, notably over a post-HS2 “alternative connectivity plan”, and on Street’s part a reluctance to rule out voting for Burnham, were he a Manchester resident.

A big and possibly electorally crucial difference, however, is that recorded in a recent Centre for Cities opinion poll – that, while over a third of Manchester respondents could name at least one of Mayor Burnham’s policies, barely 10% of West Midlanders could recall one of Street’s, despite the fact that he certainly has plenty – plus, apparently, cash. It’s a disappointing stat for someone who sculpts his reputation on getting things done.

_________________

.

[1] Which, with the exclusion of Scotland, which the Romans never properly occupied, represents what the Romans called Britannia – hence the title.