Picture credits: https://www.spiked-online.com/ and https://unherd.com/

Jon Bloomfield

The playwright David Edgar and I have written a two-part essay for Byline Times which was published before Xmas. It focuses on the role of two distinct web-sites – ‘Unherd’ and ‘Spiked’- in shaping the debate on culture wars and promoting national populist ideas across British politics. Here is a brief summary of the essay, full links below.

So, now the dust is settling, what is the ideological future of the Conservative Party? With kamikaze supply-side Trussonomics so thoroughly discredited, will Rishi Sunak and his – relatively – big-tent Cabinet return to a 2020s version of Cameronian fiscal austerity? If so, what happens to the Johnsonian cocktail of high public spending and social conservatism which proved so palatable to the voters of the Red Wall? And what is the role of online ideologues – notably writers for the websites Spiked and Unherd – in the battle for the party’s soul?

British national populism has proved much more than just a short-term political tactic, unexpectedly successful in the Brexit referendum and re-conceived as an election-winner three years later. Like the free market ideologues of Tufton Street, national populists are organised into influential groups of intellectuals and political campaigners who have gained considerable reach into mainstream media. The role of The Spectator is well-known but this article focuses on the profound influence of two websites: Unherd and Spiked.

What makes these sites so significant and successful is that many of their lead writers originate not on the right but on the mainstream and indeed the far left, and now promote ideologies that seem contradictory but – in practice – are increasingly allied.

The emergence of national populism has seen strange, paradoxical political alliances emerging within the two main political parties exemplified by the Red Tory and Blue Labour tendencies. Even stranger has been the ideological overlap between the website of a formerly Marxist, now right-libertarian think tank and the main online home of anti-liberal communitarianism. So why – on the issues that are tearing Britain apart – do Spiked and Unherd appear to be bedfellows?

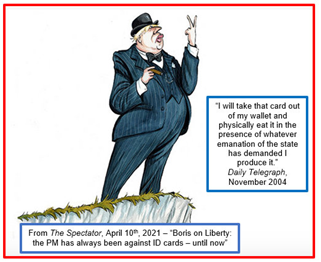

Both are prolific sites supplying a daily flow of political and cultural commentary. Spiked is an outgrowth of the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), which developed an increasingly eccentric version of Trotskyism with its magazine Living Marxism. Launching the website Spiked in 2000, its cadres – including former RCP guru Frank Furedi, polemicist and now Brexit-supporting peer Claire Fox, and Munira Mirza, later to become Boris Johnson’s policy chief – continued the RCP’s trajectory towards anti-statist, economic libertarianism while retaining its original Leninist discipline and capacity for harsh polemic.

Unherd has more conventional origins within the Conservative party. Its founder Tim Montgomerie set out its stall in Prospect arguing for a “social Thatcherism,” which would re-balance “from a conservatism of freedom to a conservatism of locality and security.” Montgomerie argued that within the Conservative Party “the magnetism of national sovereignty has finally overtaken the magnetism of free markets.” However, Unherd has also attracted former left polemicists, including ex-Labour-supporting, Prospect-editing journalist David Goodhart – now ‘Head of Demography, Immigration and Integration’ at the right-wing think-tank Policy Exchange; academic turned national-populist advocate Matthew Goodwin; trade union activist and anti-woke campaigner Paul Embery; and the ex SWP-flirting, Tory-convert vicar Giles Fraser.

The reason for this unexpected cross-fertilisation of ex-Trotskyites, traditionalist Tories and communitarian, socially-conservative Labourites is their ideological alignment on many of the key cultural controversies of the day. A fervent commitment to Brexit and belief in the unreformed UK nation-state are central, but what gives the two platforms their raison d’etre is the consistent vitriol directed at the mainstream left and the new social movements that have emerged around it over the last few decades. A bitter animosity against social liberalism and a caricatured ‘woke’ left is their most distinctive, current and common thrust. Their ideas – particularly on multiculturalism and the ‘woke agenda’ – have been eagerly lapped up by the mainstream right-wing media.

Within the Sunak government, in their various ways Kemi Badenoch, Michael Gove and Suella Braverman are all signalling their wish to return to the national-populist ‘culture wars’ agenda. Like their counterparts in Europe and the US, the national-populists want to roll-back the advances that have been made in the past 50 years. The likes of Spiked and Unherd are crucial propagandists in this battle. In particular, these two sites have mounted a consistent assault on progressivism on the major social and cultural issues of the day: climate justice, feminism and anti-racism. On three of the great social issues of our era – climate change, women’s inequalities and structural racism and discrimination – the editorial lines of Spiked and Unherd are marching in lockstep, deploying similar arguments and even phraseology, to minimise the issues or to deny that there’s any problem.

National-populism has its own logic. Mobilising ethnic nationalism; arousing fears about race and religion; attacking social liberalism; overtly or covertly promoting the ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy theory. All lead in just one direction.

This is a moment for liberals, progressives and the Left to wake up.

It’s time for them to draw on their own history and re-build the alliances that have led to so much social and economic progress in the past. In the more variegated, less homogenous world of 21st Century capitalism, finding the ways to navigate common ground between movements and build cross-class alliances is more important than ever.

The provocations of Spiked and Unherd stand in the way. At a moment when the hard-Right is showing a readiness to indulge in racist and nationalist politics reminiscent of dangerous eras of the not-too-distant past, it is time for progressives to prioritise unity, rebuild alliances which have done so much good in the past, and direct their firepower at their main opponents.

Red Tory to Blue Labour – How Spiked and Unherd are Keeping National Populism Alive – Byline Times

Fighting Back Against National-Populism – Byline Times

Jon Bloomfield has been involved with the EU’s Climate KIC programme for over a decade, helping to develop educational and training programmes and experimental projects which help companies, cities and communities to make effective transitions to a low carbon economy.