Jason Lowther

There is much to welcome in the Government’s Elections Bill which completed its second reading last month and is being scrutinised by the Public Bill Committee over the next few weeks. There has been widespread welcome to elements to clarify what’s meant by “undue influence” on voters, improve poll accessibility, prevent the intimidation of candidates and require all paid for digital political material to have an imprint. But the measures to introduce voter ID need to be handled with care.

Under the Bill, voters will be required to show an approved form of photographic identification before collecting their ballot paper to vote at a polling station for UK parliamentary elections in Great Britain, at local elections in England, and at Police and Crime Commissioner elections in England and Wales. A broad range of documents will be accepted including passports, driving licences, various concessionary travel passes and photocard parking permits issued as part of the Blue Badge scheme. Any voter who does not have an approved form of identification will be able to apply for a free, local Voter Card from their local authority.

Chloe Smith, Cabinet Office Parliamentary Secretary, argued in 2019:

Electoral fraud is an unacceptable crime that strikes at a core principle of our democracy—that is, that everybody’s vote matters. There is undeniable potential for electoral fraud in our current system, and the perception of this undermines public confidence in our democracy. We need only to walk up to the polling station and say our name and address, which is an identity check from the 19th century, based on the assumption that everyone in the community knows each other and can dispute somebody’s identity…Showing ID is something that people of all backgrounds already do every day—when we take out a library book, claim benefits or pick up a parcel from the post office. Proving who we are before we make a decision of huge importance at the ballot box should be no different.

Whilst concern about voter fraud is generally low in the UK, Electoral Commission research in 2014 identified some local areas where there appears to be a greater risk of cases of alleged electoral fraud being reported. Generally these areas were limited to individual wards within 16 local authority areas (out of just over 400 across the UK as a whole). These areas were often characterised by being densely populated with a transient population, a high number of multiple occupancy houses and a previous history of allegations of electoral fraud.

The Electoral Commission asked national and local organisations, including those representing people with protected characteristics under the Equality Act 2010, to provide evidence of how the proposals for Photo ID affected the specific groups they represent. The results showed significant concerns. Charities representing people with learning disabilities, the BAME, LGBT+, gypsy and traveller communities and people without a fixed address raised general concerns that some of the people they represent are already less likely to register and vote, and they are also less likely to have ID. Many of the responses highlighted existing difficulties their users face in accessing services requiring proof of identity, including barriers faced by people who don’t have easy access to the internet.

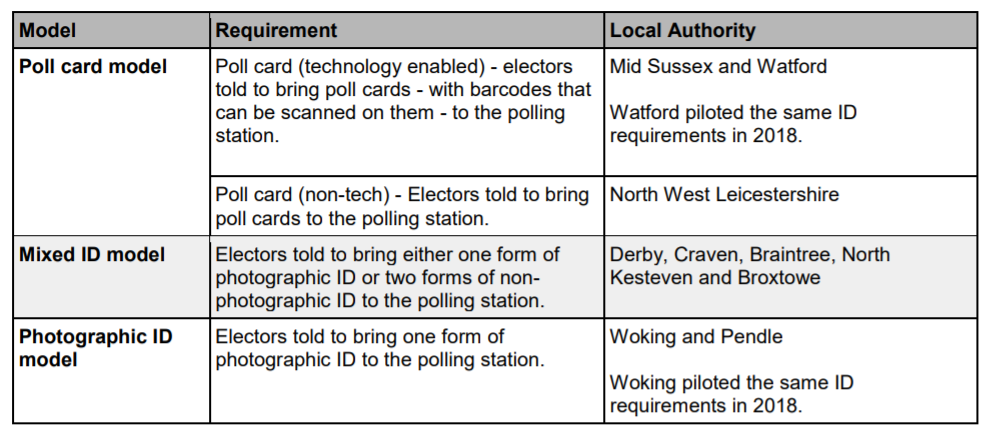

Photographic voter ID has been used in Northern Ireland since 2003, and at the May 2019 local elections, ten local authority areas in England agreed to run pilots. Interestingly, three of the ten pilot areas were in the Electoral Commission’s list of higher risk local authority areas referred to above. There were different arrangement according to three models: In two areas, people had to show a specified form of photo ID. In five areas, they could choose to show either a specified form of photo ID or two pieces of specified non-photo ID. And in three areas people could show either their poll card or a specified form of photo ID. The mixed ID model and the photo ID model both had a provision for free, locally issued ID available from the local authority, if electors did not have the required form of ID.

The Cabinet Office’s internal evaluation of the pilot declared the 2019 pilot “another success”. The evaluation aimed to assess the pilots against measures of integrity (perceptions of the voting process, and of electoral fraud), democracy & equality (awareness, voting behaviour), delivery (planning and resource implications), and cost. Some may feel that generalisability of the conclusions are limited by the range of local authorities volunteering to be involved not being representative of the country as a whole (table 1).

Table 1: 2019 pilot authorities

Source: Cabinet Office evaluation report, p.7

The Cabinet Office concluded that the photographic ID model had the most pronounced impact on the measures of integrity, with a significant increase in voter perceptions that there are sufficient safeguards in place to prevent electoral fraud at polling stations (differences in the mixed ID model were not significant). The proportion of people who did not return to the polling station varied by model, but the evaluation argues that across all models this accounted for under 0.5% of those who were checked at polling stations, the report notes ‘there are some indications that the mixed ID model was accessible for electors, particularly in more demographically diverse areas’.

As always, the devil is in the detail. Looking at the detailed results, the proportion not returning is at least twice as high in the mixed and photo ID samples (up to 0.7% of electors in two councils). And when you look at individual wards, those with the highest percentage of non returners were often those with relatively high BME populations. As LGIU pointed out in its analysis of the pilots: ‘Voter ID is not a priority for voters, who are more concerned about low voter turnout, bias in the media, and inadequate regulation of political activity on social media. Only one in four respondents to a post poll survey (24%) said electoral fraud was somewhat of or a serious problem, with more (26%) stating it isn’t a problem’.

The Electoral Commission’s overall conclusion on the pilots was ‘we are not able to draw definitive conclusions, from these pilots, about how an ID requirement would work in practice, particularly at a national poll with higher levels of turnout or in areas with different socio-demographic profiles not fully represented in the pilot scheme.’

The Joint Committee on Human Rights has also considered voter ID, and published its final report in September 2021. It called on the Government to produce clear research setting out whether mandatory ID at the polling station could create barriers to taking part in elections for some groups and how they plan to mitigate this risk effectively.

As outlined in the excellent report on the issue by Neil Johnston and Elise Uberoi of the House of Commons Library, experience in Canada (who introduced voter ID in 2008) showed that ‘a significant minority of voters in Canada struggled to prove their residence address as they lack documents that prove the address used to register to vote’.

Voter ID, of course, is one of a range of measures which Government could take to change election arrangements. The Missing Millions report made 25 recommendations to enable increased participation, such as encouraging recipients of National Insurance number notification letters to register online, and Government funding and support for a National Voter Registration Drive. Most polling clerks experience having to turn away electors because their names are not on the electoral roll in the first place, arguably this is a much greater threat to our democracy than the fears of false identities which voter ID seeks to address.

The Government has not yet shown how voter ID will operate in England without adversely affecting certain minority and disadvantaged groups. Until issues such as costs and access are fully addressed, it needs to proceed with caution.

Pingback: Voter ID gets Code Red | INLOGOV Blog