Marina Pera and Sonia Bussu

In a recent article titled Towards Democratisation of Public Administration:Public-Commons Partnerships in Barcelona, part of a Special issue on The International Journal of the Commons (edited by Dr Hendrik Wagenaar and Dr Koen Bartels), we explored public-commons partnerships in Barcelona through a relational lens, examining how they might be contributing to deeper democratisation of public administration.

The commons refer to those cultural and material resources collectively managed by the community and represent an alternative to both the state and the market. Recent literature emphasises the capacity of the commons’ prefigurative politics to develop alternative institutions to neoliberal regimes and/or deliberative and collective forms of resource management. The grassroots movements managing the commons often take an oppositional stance to the state, but they might also depend on its resources. By the same token, the state has an interest in supporting assets and services managed as commons, which offer flexibility and efficiency, while encouraging citizen participation in local politics.

Within political contexts sympathetic to progressive socio-economic projects, such as new municipalism in Barcelona, formalised alliances between the local state and the commons started to emerge, facilitating the development of novel policy instruments that respond better to the demands of the commons and open opportunities for more participatory policymaking. So-called public-common partnerships are long-term agreements based on cooperation between state actors and the commons members. In our paper, we wanted to understand better the relational work behind these partnerships and the role of boundary spanners that build bridges between two worlds, such as the state and the commons, which are often quite distant in terms of visions of local democracy and the language to articulate such visions. We take the case of the Citizen Asset Programme (CAP) in Barcelona to explore the relationships between public officials and commons members, highlighting how these collaborations shape governance practices and can help foster a collaborative culture within public administration.

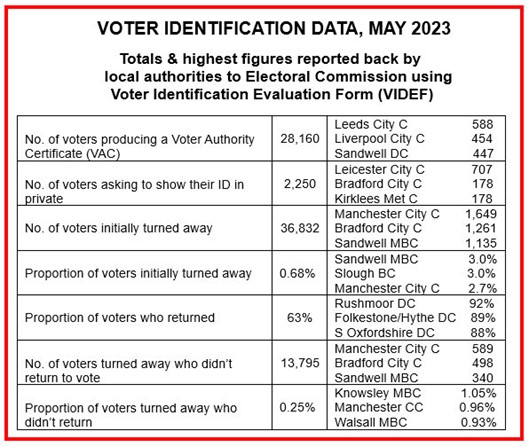

CAP was approved in 2016 and aims to create the institutional framework to recognise and support commons-managed municipal assets in the city. Based on qualitative analysis of interviews with public officials and commons members involved in the partnership, as well as official documents, we drew out insights on the relational dynamics that facilitated the creation of two policy instruments under CAP: The Community Balance Metrics and the Social Return on Investment of Can Batlló. The first one is a set of indicators to evaluate the performance of community-managed assets considering their transformative potential and including dimensions of internal democracy, care, inclusion, and environmental sustainability. The second helps to measure the value of activities and volunteer work carried out in the community centre of Can Batlló.

Through a series of vignettes depicting the different state and commons actors involved, we examined how they forged alliances and employed creative thinking to manage conflicts, resistance, and scepticism from both the local administration and the grassroots movements. Public officials from the Active Democracy Department were able to build trust among commons representatives by recognising their needs and potential. They explained the workings of public administration in a clear language. They created spaces of open-ended dialogue between grassroots movements and different departments to facilitate the development of policy instruments, measures and indicators that valued the commons’ innovative work, while still coherent with existing legal requirements. For instance, a working commission was set up involving members of Can Batlló, the Legal and the Heritage Department, as well as representatives of the District administration. This public-commons partnership developed a comprehensive agreement to regulate asset transfers, which fully recognises the social and economic value of the commons.

By the same token, the commons members played a crucial role in communicating to grassroots movements the work of the Active Democracy officials and build mutual trust. On the one hand, they helped the commons understand feasibility issues of their demands; on the other they pressed the public administration for greater transparency and creative interpretation of existing regulatory framework to strengthen democratic values underpinning asset transfer agreements.

Two cooperatives supported these partnerships as consultants. They contributed knowledge of innovative public policies from across the world. They also facilitated knowledge sharing to encourage cooperation between commons members and state institutions, for instance by inviting grassroots groups from other parts of the world to share their experience of working with the state.

The work of these public-commons partnerships is gradually reshaping the administrative culture and fostering more transparent and democratic working practices within the public administration. An example is the joint work to develop the Community Balance Metrics, which helps evaluate the performance of the commons using indicators agreed upon by both local public administration and the commons. However, these processes face a number of challenges, as they clash with established working routines and performance evaluations of public administrators that hardly ever value participatory work. Existing literature suggests that despite the introduction and encouragement of new practices, there is a tendency to revert to traditional policymaking methods when faced with unexpected problems. When boundary spanners that had supported the partnership exit the process, they can leave a vacuum that is hard to fill and that can jeopardise the partnership. In Barcelona, ongoing discussion between Can Batlló members and the City Council on who is responsible for funding the refurbishment of one of Can Batlló’s building is causing friction within the partnership and some of the work has stalled.

Inevitably this collaborative work is hard to sustain, but in the face of multiple and overlapping crises facing local government, these public-commons partnerships are also beginning to open safe space to experiment and do things differently.

Picture credit: Victoria Sánchez.

Sonia is an Associate Professor in INLOGOV. Her main research interests are participatory governance and democratic innovations, and creative and arts-based methods for research and public engagement. She led on projects on youth participation to influence mental health policy and services, coproduction of research on health and social care integration, models of local governance, and leadership styles within collaborative governance.

Marina is a researcher at Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). She holds a PhD in Public Policy from UAB and a M.A. in Sociology from Columbia University (New York). She has been a visiting scholar at CUNY Graduate Center (New York) and at INLOGOV, University of Birmingham. Her research interests

include community assets transfer, democratisation of public administration, community development and public-common partnerships.