Chris Game

Brigid Jones, currently to be seen on YouTube promoting Birmingham City Council’s customer access strategy, and incidentally the city’s bus lanes, is a UoB alumna – though sadly having preferred to study Physics, rather than gain an invaluable early insight into the workings of local government through INLOGOV’s undergrad Public Policy degree.

Happily, she somehow overcame this early career hiccup, was elected as a Labour councillor to Birmingham City Council in 2011, impressively quickly became the Cabinet Member for children, families and schools, and since 2017 has been the Council’s Deputy Leader.

It was in that Cabinet role, though – five years ago almost exactly – that Cllr Jones first attracted significant national as well as local attention, by noting that, despite being the “very proud corporate parent” of the nearly 2,000 children then in the Council’s care, accountable for a £1.2 million budget and thousands of staff, if she herself wished to start a family, she – as a councillor with a taxed £25,000 cabinet allowance – had been told she would “most likely have to step down from my council position”.

Because, although the Council’s (male) Chief Executive was reportedly “working on a policy”, it was yet to be considered by the Cabinet, or probably anyone else. The apparent rationalisation – “we haven’t had a pregnant Cabinet member in Birmingham for a very long time” – revealed as much about the recruitment and societal representativeness of councillors as about their financial remuneration.

The CE sounded suitably embarrassed, for, however few UK councils would have been in significantly more considered and supportive positions, for the biggest of them all, that was surely no refuge. Still, barely 20 months later, the Council produced a policy – not merely, to coin a phrase, ‘oven-ready’, but fully baked.

The Birmingham Post/Mail could report that Birmingham councillors – all councillors, note, not just Cabinet members – “will for the first time be entitled to maternity and paternity pay”. Councillors would continue to receive their basic allowance for at least six months of maternity leave, and senior councillors with additional responsibilities would get 90% of their Special Responsibility Allowance for the first six months and at least a basic allowance up to week 39. Better terms, apparently, than for staff – prompting, understandably, calls for council workers’ maternity terms to be improved too.

Thanks substantially no doubt to Cllr Jones’ work ‘behind the scenes’, Birmingham’s present Members’ Allowances Scheme and particular the Maternity, Paternity and Adoption Pay sections, could, in my albeit limited experience, serve as at least a baseline model for UK councils generally.

A few examples: Members on maternity leave continue to receive full allowances for six months, possibly extendable; adoptive parents ‘newly matched’ with a child by an adoption agency ditto; shared parental leave negotiable for one or two parents, including same sex.

There’s nothing in the Scheme that’s obviously either exceptional or exceptionable – just reasonable modern-day practice for a public organisation conscious of the difficulty it demonstrably has attracting a representative quota of younger and particularly female members.

On the other hand, you may recall the row back in February when the Government rushed through Parliament a law-change allowing Cabinet ministers – specifically the then eight-months pregnant Attorney General, Suella Braverman – to have six months’ maternity leave on full pay plus salary costs for a temporary replacement.

Back at work recently, Braverman was understandably grateful for the uniquely tailored special treatment – unavailable to ‘ordinary’ backbenchers such as Labour MP Stella Creasy, who four months later, like others before her, had had her request for full locum cover for her second child rejected, on the almost too-good-to-be-true grounds that it was “misconceived” – the request, apparently, not the actual child. Either way, she was, as they say, contemplating legal action.

If our national Parliament acts in this rushed, last-minute, blatantly discriminatory fashion, it would perhaps be surprising if local government’s record were strikingly better – and the evidence shows it isn’t.

The good news: statistically overall there appears little explicit Parliament-style discrimination between senior cabinet-level councillors and ‘ordinary’ councillors. Bad news: three-quarters of councils seem to have no councillor maternity/paternity policies at all. Broadly encouraging news: just two years ago, that three-quarters was 93%.

The statistics come from an admirably comprehensive study based on responses from over 90% of English councils to Freedom of Information requests from the Fawcett Society, the campaigning charity for gender equality and women’s rights.

There seemed no obvious reason why West Midlands councils should be statistically exceptional, and they aren’t. Just two – Birmingham and Wolverhampton – have formal policies in place for maternity, paternity, adoption and kinship care for all councillors. Coventry claimed ‘informal’ policies, Walsall didn’t respond, leaving Dudley, Sandwell and Solihull with apparently no policy at all.

Nationally, roughly a quarter of English councils reported having maternity or paternity policies in place for their ‘ordinary’ and/or senior councillors, perhaps the most positive feature of which figures being that just two years ago they were 7% and 8% respectively.

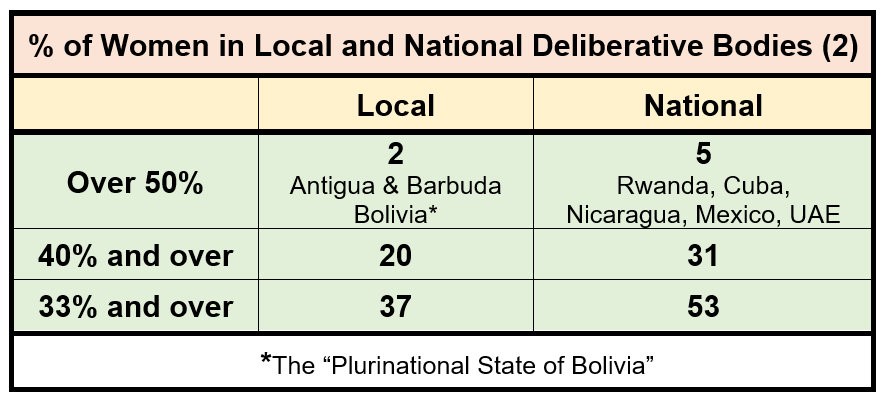

Some way to go, evidently. And the same – relatedly, the Fawcett Society would suggest – goes for women’s representation on councils generally. Across England as a whole, it found just 35% of all councillors are women – less than a 1% increase since the 2019 elections.

Which means, “at that rate of change, we won’t see gender parity in local councils until 2077 – over 50 years away”. Hence, it would argue, the importance of maternity and paternity policies, in addition obviously to their intrinsic merits.

However, such projections depend on your baseline. And, as a seriously boring, nerdy person, I happen to know that exactly 50 years ago, in 1971, the proportion of English women councillors was just 12% [J.Z. Giele & A.C. Smock (eds.), Women: Roles and Status in Eight Countries (1977), p.17]. From which starting point today’s 35% reaches 50% by – wow! – 2055.

Either way, it’s effectively a working lifetime’s wait – and more possibly for some, like the North Yorkshire district with just 3 women councillors out of 30 and an Anglo-Saxon name whose modern-day meaning is ‘lack of courage’: Craven. The Fawcett study found 10 councils in all with under 20% of women members, the others in ascending order being West Berkshire, Swale, Ashfield, Hambleton, Cherwell, Castle Point, Huntingdonshire, Essex County, and Wycombe.

To finish, though, on at least a relatively high note, these 10 are outnumbered by the 14 councils with over 50% women members, a selection striking too for its obvious diversity. This time in descending order: Brighton & Hove (56%), Cambridge, Islington, Nottingham, East Cambridgeshire, Havant, Manchester, Norwich, South Oxfordshire, Gateshead, Kingston upon Thames, South Kesteven, South Tyneside, and Liverpool.

Which, returning home as it were, begs the question: if councils as diverse as these can achieve 50%+, why is it Birmingham can manage barely one in three? Cllr Jones, your work is far from done!

An earlier version of this blog was published in the Birmingham Post on 23rd September

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.