Jason Lowther & Chris Game

‘Code Red’, for anyone even approaching the generation of this blog’s more senescent author, has to cue the memorable final Tom Cruise/Jack Nicholson courtroom scene in Aaron Sorkin’s film, A Few Good Men. Indeed, said author has actually adapted and used it previously in these very columns:

Lieut. Kaffee (Cruise): “Did you order the Code Red?” Col. Jessup (Nicholson): “YOU’RE GODDAMNED RIGHT I DID!!!”

In the film, ‘Code Red’ is a term used for any extra-judicial punishment or action taken against US marines for the purposes of humiliation or worse. Its function is, essentially, to deal with issues that can’t be solved using the normal legal framework.

In substantial contrast, the UK Government’s Code Red, though hardly a regular feature of our media’s political reporting, is at the very core of our modern-day governmental system. It is a (arguably the) key instrument of the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA), the Government’s centre of expertise for infrastructure and major projects, reporting to the Cabinet Office and HM Treasury.

Formed in 2016, the IPA’s intended function is to increase government efficiency and save public money by monitoring and ‘scoring’ the viability of its literally hundreds of infrastructure and major projects … and does so with an effectiveness that has some Ministers in the present Government viewing it as more of a PI(the)A.

This already substantial introduction does have a local government-relevant point – promise! And it is no blog’s function to deliver lecturettes, which in this instance are both available and well illustrated, from the Institute for Government and the IPA itself in its very recent 2022 Annual Report.

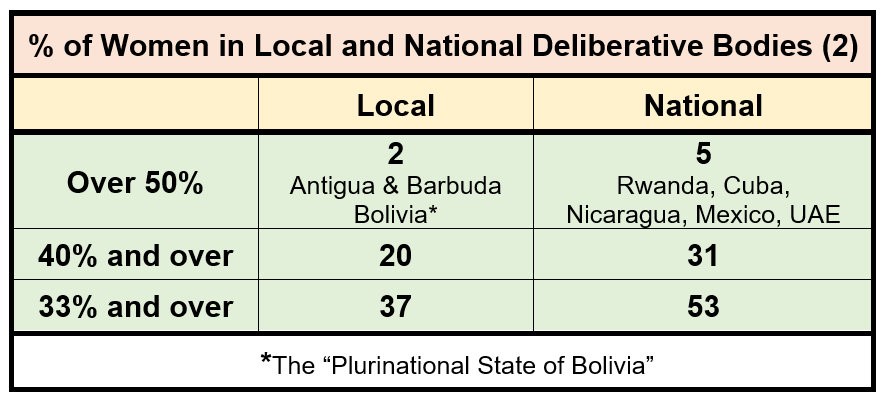

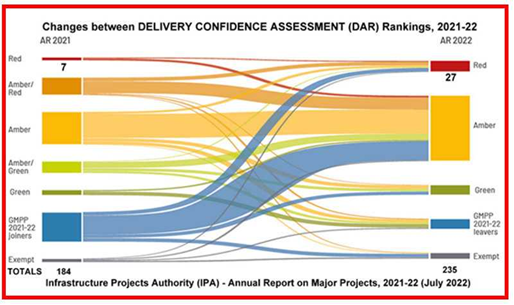

What follow, therefore, are a few shortish paragraphs outlining the IPA’s work, and two graphics from that 2022 Report worth, if not the proverbial thousand words, certainly a good many. We then focus on the issue of voter ID in England, reporting the government’s own assessment on the risks involved, and conclude that Government has still not yet shown how voter ID will operate in England without adversely affecting certain minority and disadvantaged groups.

The focus of the IPA’s work is the Government Major Projects Portfolio (GMPP), comprising this year 235 projects with a total Whole Life Cost of £678bn and estimated “monetised benefits” of £726bn, delivered by 18 departments and their arm’s-length bodies.

The projects are divided functionally into four categories, biggest-spending being Infrastructure & Construction (70 projects: £339 bill. whole life cost; £356 bill. “monetised benefits”) – high investment projects, including improving the UK’s energy, environment, transport, telecoms, sewage and water systems, and constructing new public buildings. Dominated financially, and in the IPA’s ‘unfeasible’ delivery confidence rankings, by the Dept for Transport’s HS2 (£72 – 98 billion) and Crossrail (£19 billion+) projects.

Transformation and service delivery covers projects changing ways of working to improve the relationship between government and the UK people, and harnessing new technology. Example: Vaccines Task Force.

Military Capability ispretty self-explanatory. Example: the Future Combat Air System – clever, mid-2030s stuff like uncrewed aircraft and advanced data systems.

ICT projects enable the “transition from old legacy systems to new digital solutions” to equip government departments for the future. Example: Emergency Services Mobile Communications.

Now to the interesting bit: the actual ‘confidence rankings’, or in the above cases of HS2 and Crossrail ‘no confidence rankings’. The official term is Delivery Confidence Assessments (DCAs): judgements of the likelihood of a project delivering its objectives to time and cost.

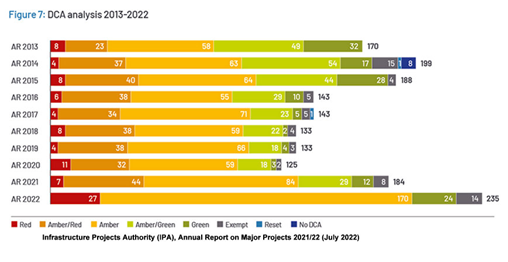

In essence, it’s a basic traffic light system. Green represents high likelihood of successful delivery of the project on time, budget and quality; amber: successful delivery feasible, but significant issues already exist, requiring management attention; and ‘Code Red’: unachievable, not a cat in hell’s chance; major issues everywhere, with project definition, schedule, budget, benefits – all at this stage apparently irresolvable.

Given the variables involved, it sounds more than a touch crude, and two additional ratings were added: amber/green – successful delivery probable, if given constant attention; and amber/red – successful delivery doubtful, major risks apparent in numerous key areas, urgent action needed.

Usefully added, it seemed, as unqualified amber regularly took between 40% and 50% of ratings (see Fig.7 below). But no, looked at another way, the “average project rating worsened from Amber/Green in 2013 to Amber in 2020” (p.16). It obviously couldn’t possibly be the quality of the proposed projects, so it had to be the assessment system, which accordingly for the 2022 assessments was changed.

But oops! The number of red assessments nearly quadrupled, almost equalling the previous four years’ red totals between them – but that’s OK, because the average project rating, we are assured, “has improved over the past two years”, though it’s not entirely transparent in the second flow chart.

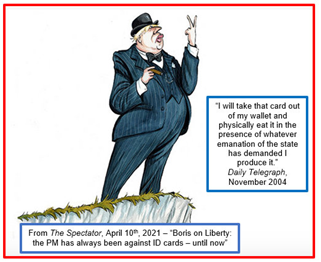

Which brings us back to Code Reds. Unlock Democracy, the democratic reform campaign group – and also the Daily Mirror – reported last week that “the Government’s own rating system has given the Elections Bill implementation a code red, which is defined as successful delivery of the project appear[ing] to be unachievable.” Followed by the Association of Electoral Administrators announcing that it “no longer believes it is possible to successfully introduce Voter ID in May 2023.”

The Government’s “Electoral Integrity Programme (EIP)” has been red rated in the IPA’s annual report (see page 58). The report summarises the Programme as ‘implementing changes arising from the Elections Bill. The Elections Bill makes provision about the administration and conduct of elections, including provision to strengthen the integrity of the electoral process. Reforms will cover: overseas electors; voting and candidacy rights of EU citizens; the designation of a strategy and policy statement for the Electoral Commission; the membership of the Speaker’s Committee; the Electoral Commission’s functions in relation to criminal proceedings; financial information to be provided by a political party on applying for registration; preventing a person being registered as a political party and being a recognised non-party campaigner at the same time; regulation of expenditure for political purposes; disqualification of offenders for holding elective offices; information to be included in electronic campaigning material’.

DLUHC’s commentary on this result noted the deteriorating assessment and added: ‘The IPA Gate 0 Review of February 2022 concluded that the programme Delivery Confidence Assessment is rated Red and that the programme needs to address key risks related to the suitability of the structure, approach and governance given its complexity and delivery focus, suitability of its minimum viable and digital products, and its lack of contingency to deliver against immovable deadlines’.

Reassuringly, the department felt that ‘the programme is addressing these points’. Meanwhile, the estimated ‘whole life costs’ of the programme jumped from just under £120m to over £145m.

Unlock Democracy’s Tom Brake has reportedly written to Levelling Up SoS Greg Clark saying ‘It would be highly risky to attempt the first roll out of photo voter ID for the largest election in the UK, without having tested it on lower turnout elections beforehand’. This echoes Jason Lowther’s comment on this blog almost a year ago that ‘The Government has not yet shown how voter ID will operate in England without adversely affecting certain minority and disadvantaged groups. Until issues such as costs and access are fully addressed, it needs to proceed with caution’.

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.