Nicholas Hicks and Jon Bright

In this blog, we discuss a major success in health policy that’s been largely forgotten.

What happened?

During the 2000s, a government strategy to tackle health inequalities in England led to a reduction in geographical differences in life expectancy. Furthermore, this success reversed a trend that had been increasing. It was achieved by reducing death rates caused by coronary heart disease.

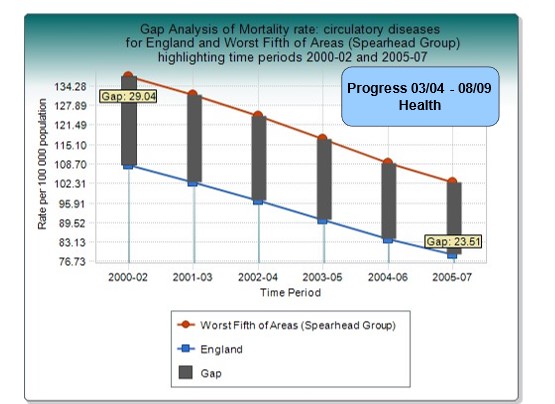

The chart below shows an overall reduction in coronary heart disease mortality and a reduction of nearly 20% (19.07%) in the gap between the national average and the poorest areas. [Barr et al 2017]

This is the only period in the last 50 years when inequalities in death rates between rich and poor have narrowed. It was a considerable achievement and an historic result.

What was the impact in terms of lives extended?

This policy meant that many millions of people lived longer and healthier lives. Much of the benefit was probably due to reductions in smoking and managing risks such as high blood pressure and cholesterol. In 2000, 38% of the adult population smoked and smoking was twice as common amongst those on low incomes. Today, only about 13% of the adult population smoke, the lowest since records began.

But this achievement was not down to health policy alone. Importantly, it was also due to coordinated action across Government to tackle inequalities more generally. This is because many of the factors that affect health lie outside the health sector.

What were the policy drivers?

This work started in 2000 with the NHS Plan (that committed Government to publishing inequality targets), and the Department of Health’s National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease, and continued over several years.

These policies led to a national commitment to reduce inequalities. In the wake of the NHS Plan, the Government set Inequalities targets and incorporated them into national Public Service Agreements (PSAs). These Agreements required central government Departments to do better in those parts of the country where outcomes were poorest. This applied not only to health but also to low income, family functioning, education, employment, and crime. These wider issues are major influences on people’s health and targeted action on these made it more likely that health-specific interventions would succeed.

PSAs defined the goals of the 2002 and 2004 Comprehensive Spending Review. Departmental budgets were only agreed once each Department produced credible plans showing how they would contribute to the inequality targets.

What did all this mean in practice for people living in poorer regions?

Health-specific interventions included smoking cessation clinics; improving the distribution of GPs – many disadvantaged areas had no GP service; more resources for disadvantaged areas; national guidance on best practice; and improved access to mental health services. Action to tackle the wider causes of poor health included improving housing (the Decent Homes Standard); increasing household income (the Minimum Wage, Tax Credits); investment in education and skills; reducing the number of young people not in education, employment and training; teenage pregnancy prevention; and investment in early years (Sure Start and family support).

This approach is consistent with Prof Michael Marmot’s conclusions in his 2010 report, ‘Fair Society, Healthy Lives‘ .

What did evaluators find?

Evaluators found that regional inequalities decreased for all-cause mortality and that the strategy was broadly successful in meeting its ambitious targets. Writing in 2017, Barr et al they concluded that ‘future approaches should learn from this experience”. They noted that current policies were probably reversing this achievement of the previous decade. See also Holroyd et al’s systematic review.

In our main paper REASONS TO BE HOPEFUL we discuss the evaluations in more detail.

What lessons should we draw?

There are five main lessons to draw from this evidence:

- When Government takes a coordinated approach to a problem – and sticks with it over time – the results can be impressive, even with problems thought to be intractable.

- Health is a good proxy for Levelling Up. Narrowing the health gap between regions is a good proxy for ‘levelling up’ more widely. Health inequalities are in large part due to poverty, poor education, and poor housing. Regional inequalities in educational attainment and crime also narrowed.

- Leadership and persistence are essential. A ‘whole of government’ approach requires good cross departmental working, full engagement with local government, and leadership from the Prime Minister.

- Tackling the nation’s problems needs longer term policy making so successful approaches don’t fizzle out whenever there’s a change of Government. As we’ve seen, benefits achieved up to 2010 may have been lost by 2017. Maintaining progress requires cross-party, long-term collaboration.

- This approach worked by influencing mainstream budgets via better targeting and evidence-based interventions, rather than relying only special ring-fenced funding

Today, the big health challenges today are obesity, diabetes and related conditions. Again, poorer populations are much more affected. Will today’s politicians rise to the occasion?

Dr Nicholas Hicks BM BCh FRCP FRCGP FFPH is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow, Nuffield Department of Primary Health Care Sciences at the University of Oxford and a Senior Strategy Advisor, Department of Health and Social Care. He is also an Associate Fellow, Green Templeton College, University of Oxford. He was seconded to the Department of Health Strategy Unit and helped draft the inequalities chapter of the NHS Plan in July 2000 ([email protected]).

Jon Bright is a former civil servant who worked in the Cabinet Office and Department of Communities and Local Government between 1998 and 2014.

References

- Meadows D. Leverage points: places to intervene in a system.

- NHS Plan. A plan for investment; a plan for reform. Department of Health (2000): 106-7

- Health inequalities – national targets on infant mortality and life expectancy – technical briefing . Department of Health March 2002

- Spending Review 2002: Public Service Agreements, HM Treasury 2002 para 1.12

- Holdroyd I, Vodden A, Srinivasan A, Kuhn I, Bambra C, Ford JA. Systematic review of the effectiveness of the health inequalities strategy in England between 1999 and 2010. BMJ Open. 2022 Sep 9;12(9):e063137. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063137. PMID: 36134765; PMCID: PMC9472114.