Tom Collinson

If there has been one mantra by which government policy has claimed to have lived by during the COVID-19 crisis, it is that it has been led by, guided by or that it is following the science. Intended to strike a reassuring tone, the claim to evidence was routinely emphasised by the government as either the Prime Minister or a deputy was flanked by a member of SAGE. When questioned on his previous disavowal of experts by Sky News at the beginning of the crisis, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Michael Gove, noted that these were economists he had referenced in the past, it was not established medical facts; suggesting that this time was different and that this science was different.

One article by the New York-based magazine The Atlantic even went so far as to claim that ‘Britain Just Got Pulled Back from the Edge’ as ‘the institutions and positions of state were…clicking into gear.’ While it appeared to be a rosy picture at the start, with the government publishing the scientific advice online, with a gesture that it would continue to do so, this tone quickly unravelled as the Guardian reported that non-scientists seemed to be advising government; there was no list of who exactly was in the SAGE group and why there were no (publicly available) minutes of the meetings and government advice was no longer transparent. Some of this has now changed.

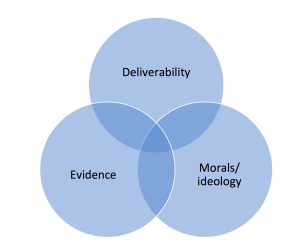

All this has provoked an interesting question of the relationship between science, evidence and data-analysis with policy-making in the UK. How does one affect the other? Is it possible for one to distinguish between various forms of evidence in the policy-making process and make a judgement on which is the most appropriate? To distinguish between mathematical modelling, so-called evidence-based policy-making (that which traditionally elevates the role of Randomised Controlled Trials) and place-and-people contextualised policy? Is it possible to have what Kant called a constitutive judgement in public-policy? (I.e. a judgement which is not based on any further assumptions, hypothetical conditions or suppositions, such as values, narratives and aesthetics). For the past decade or so, there has been a growing literature on all of these questions and the urgency of the current pandemic has enlivened them.

These questions are of increasing interest to academics, journalists and opposition parties in the Anglosphere. With regards to the United Kingdom, the establishment of an ‘Independent SAGE group’ has been indicative of some dissent from the government’s claim to scientific unity.

For local government, these issues have taken on another interesting dimension, one that examines the relationship between governance and the collection and application of evidence in policy responses. In a report on the global picture of city-governments, the OECD has distinguished between two types of evidence-led responses. The first discusses local governments as instruments or ‘implementation vehicles of national measures such as confinement’. The second acknowledges the experimentation of ‘more bottom – up, innovative responses while… building on their unique proximity to citizens.’

Building on this insight, we can begin to describe a temporal framework, which provides further detail to the OECD’s report on the times when local government have been able to articulate their own evidence-based response and when the information and decision-making lies more in the hands of central government.

While it is still unclear where we are on the timescale of the virus or the response to it – which indeed make the articles in this post preliminary – this framework can be outlined on the basis of the short, medium and long term response to the epidemic. Such an approach is based on how councils themselves are articulating a response (using similar language such as the ‘rescue’, ‘recovery’, ‘rebuild’ or, ‘hammer’, ‘dance’ and ‘reconstruction’ as distinct phases in the plans).

Categorising policy responses in this way has a lot of precedent in the field of economics. With regards to the economics of a crisis, the same typology has been outlined by Professor Andy Pike, who’s presentation to the ‘Major Economic Shocks Workshop’ at the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth addresses the types of policy responses available with regards to the local economy, businesses, supply chains and labour markets in the three different time periods. The important point here is that in the short-term responses are direct, and contingent on the problem, whereas long-term responses are open-ended and rely on change. Short-term employment issues for example are addressed through subsistence allowances, while (re)training and entrepreneurship should be leveraged in the long-term. The same applies to supply chains; the short-term goal is to secure capacity and jobs through say refinancing, while in the long-term diversification and innovation is required.

Focussing on short-term strategies during the current epidemic and lockdown, the measures taken have exhibited the direct qualities that Pike addresses. However, these have often been delivered by way of decisions and information collected in the devolved governments and Downing Street. While there have been ongoing efforts by local authorities to assess immediate likely impacts – as seen in Cardiff and the West Midlands – the role of councils has largely been to act as something of a lightning rod (or courier, depending on how you judge their efficiencies) for UK government policies. While there has been some contestation around these matters from local councils, for example in the early closure of parks, the wide picture has been one of convergence throughout the country in a number of areas of practice, including areas of communication and awareness rising, social distancing, confinement and taking targeted measures to help vulnerable groups. In many cases, this has been guided by national government regulations and the ‘dos and donts’ policy responses, financial backing of £3.2bn to be awarded to councils in England to ensure a continuation of services, as well as some financial restrictions or ring-fencing.

The reliance on central government publications and financial backing has characterised the issue of supporting businesses and economic recovery too, where councils are in the front line for conducting policies made primarily in London but also Cardiff, Edinburgh and Belfast. While there may be some differences between the England and the devolved assemblies – for example on the differences in the administration of business support in Wales and England, or the degree of discretion councils are exhibiting when it comes to business support, the general theme of subsistence pay to employees, business relief and grant funding through councils has taken the same shape throughout the country, as we can see from the following examples:

- In England, the business relief announced by the Chancellor is being paid for by councils through the Small Business Grants Fund and the Retail, Hospitality and Leisure Grant Fund, and reimbursed to local authorities should the guidance published by the MHCLG be followed.

- There is £6 billion in local authority payments of the Central Share of retained business rates that were due to be made over the next three months.

- A £500 million Hardship Fund ‘of new grant funding to support economically vulnerable people and households in their local area’ administered through existing ‘local council tax support schemes’.

- In Wales, the Welsh Government are offering a years relief on business rates to shops, leisure and hospitality businesses, and also offering small grants. Local councils are calculated to have distributed £508m to 41,000 businesses by the end of April.

- In Scotland, Local Authorities are administering Small Business Support Grants as well as Retail, Hospitality, Leisure Support Grants of up to £10,000 and £25,000 respectively.

- Similarly, in Northern Ireland a grant scheme of £25,000 for Retail, Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure has been offered, should the criteria outlined by the Northern Ireland Executive be followed.

In one of the foundational texts of modern political science, Alexis de Tocqueville describes the governance structure of the ancien regime, whereby all administrative corridors in French political life led back to the King. Intendants hired by a King to administer a province in-turn hired a sub-delegate to administer canons, where the happiness or misfortune of individuals depended entirely on ‘the whole operation of the central government’. The argument for arranging matters in this centralised manner was a financial one – to levy taxes in order to guarantee the State’s safety. But this ultimately led to the downfall of the regime itself. While I’m not comparing the UK Government to the House of Bourbon, modernity offers a number of examples where centralisation – justified because of finance and security – tends towards political and social disintegration. Further examination will do well to determine whether there is a different path forward in the long-run response to this crisis.

Tom is a postgraduate researcher with an MA in Political Thought and a BSc in Economics and Politics from the University of Exeter. His main research interests are in modern political thought, with particular expertise in the political philosophy of Hannah Arendt and Karl Jaspers, on whom he wrote his thesis, rethinking the concept of political participation and civic action in modernity. Tom is now researching the role of local and central government responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, inspecting how they complement and contrast one another. He tweets at @tzcll.