Chris Game

I’m not unrealistic. I didn’t expect the Queen in the few hundred words written for her Queen’s Speech to chatter on that much about local government and councils – and she didn’t. I did think, though, they might get some attention in the 150-page Background Briefing Notes. But, no. In the literally brief note on English Devolution (pp.109-10), ‘councils’ per se aren’t mentioned. The search did, however, make me realise how crowded it’s going to be out there, as “each part of the country” gets “to decide its own destiny”.

The Government “remains committed” to the Northern Powerhouse, Midlands Engine, Western Gateway, and, I think, the Oxford-Cambridge Arc. The 38 Local Enterprise Partnerships certainly aren’t going anywhere soon. Indeed, they may well be hoping to get their hands on the UK Shared Prosperity Fund that will replace EU Structural and Investment Funds. And quite possibly too on the PM’s own £3.6 billion Towns Fund, with, for starters, 100 Town Deal Boards, chaired “where appropriate” by someone from the private sector.

Then there are the UK Government agencies that Johnson wants to relocate out of London, with their existing civil servants or any who aren’t “super-talented weirdo” enough to pass the Dominic Cummings test.

The one democratic element of this increasingly crowded world that does receive more than a passing mention in the Briefing Notes are Mayoral Combined Authorities (CAs) and City Region Mayors, with talk of increasing the number of mayors and doing more devo deals. There weren’t many stats in this section, but one did catch my eye: “37 per cent of residents in England, including almost 50 per cent in the North, are now served by city region mayors with powers and money to prioritise local issues.”

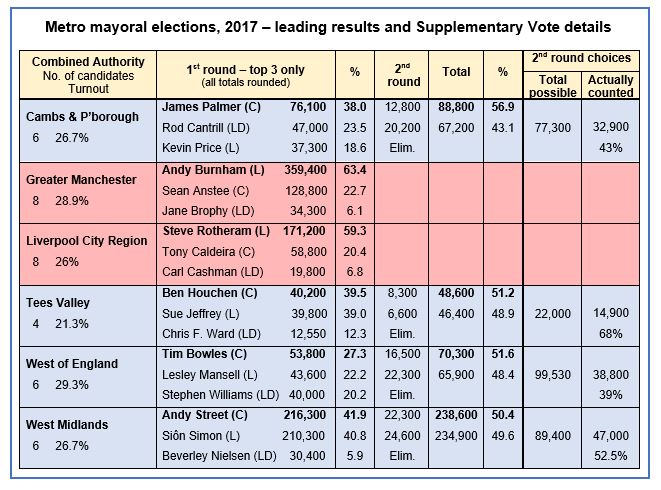

With CA mayoral elections coming up in early May, I did a few quick sums. The current party split among the nine elected mayors, including London, is 5-4 to Labour. The population split, though, is close to 3-1, with Mayor Andy Street’s West Midlands contributing over half the Conservative total. And Street’s victory over Labour’s Siôn Simon in May 2017 was knife-edge: by 0.7% of the 523,000 votes cast.

I sense you’re ahead of me. If, in the coming May elections, West Midlands voters were to return a Labour mayor, leaving Conservative mayors governing, say, barely one in eight of that 37% of residents, would a Conservative PM still be as enthusiastic about devolution to mayoral CAs? We know for near-certain that Theresa May wouldn’t have been, but Johnson, as on most things, is less predictable.

Anyway, it seemed worth asking: what would happen in the May mayoral elections, which include London this time, if everyone voted just as they did in December’s General Election? Happily, Centre for Cities’ Simon Jeffrey got there first, so the stats are his, the interpretation mine.

First, though, a quick reminder of the broader context of those 2017 mayoral elections, and what’s happened since. When Andy Street launched his bid for the West Midlands mayoralty, and even when he was officially selected as Conservative candidate, there looked like being only five of these new CA mayors.

Moreover, all five – Greater Manchester, Liverpool and Sheffield City Regions, Tees Valley, and West Midlands – might easily, given their borough councils’ political make-ups, have produced Labour ‘metro mayors’. Whereupon, it seems likely that, to say the least, Prime Ministerial enthusiasm for serious devolution to metro mayoral CAs would have waned somewhat.

However, things changed. Sheffield’s election, following a dispute over the inclusion of Derbyshire local authorities, was postponed until 2018, and two far less metropolitan (and more Conservative-inclined) CAs were established – West of England (Bristol) and Cambridgeshire & Peterborough – just in time for the 2017 elections.

With Tees Valley also going Conservative, Prime Minister May saw an initially possible 0-5 redwash turn into a remarkable 4-2 triumph – as reported on this blog. The political merits and possibilities of devolution, particularly to the West Midlands – bearing in mind that Labour overwhelmingly controlled Birmingham Council and formed the largest party group in five of the other six boroughs – suddenly seemed much more obvious.

Since then, though, the pendulum has swung. A reconfigured Sheffield CA and new North of Tyne CA have both elected Labour mayors, evening up the CA party balance at 4-4, but giving a score among the now ‘Big 5’ metros (populations over 1.3 million) of 4-1 to Labour, including Greater London Mayor, Sadiq Khan.

Jeffrey’s sums show that Mayor Khan would be re-elected easily, likewise Labour’s Steve Rotheram in Liverpool. In Greater Manchester, Labour’s Andy Burnham would be re-elected, but with a considerably reduced majority. And the collapsing ‘red wall’ would have more than doubled Conservative Mayor Ben Houchen’s majority in Tees Valley.

And so to the West Midlands, which also saw plenty of “Red wall turning blue”, “No such thing any more as a Labour safe seat” headlines. It felt as if the Conservative vote had to be ahead, and it was … but by under 3,000 out of 1.18 million, or 0.2%!

Yes, even replicating the Conservatives’ most decisive electoral win for a generation, it could be that tight. And, if it were Labour’s eventual candidate who edged it, that would see Labour metro mayors as the elected heads of government in London and all four largest city region CAs, representing nearly a third of the English population. ‘Everything still to play for’ seems an understatement.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.