Jörgen Tholstrup

What’s the mission of health care?

I’ve been working as a physician and gastroenterologist both in Denmark and Sweden for more than 30 years. Over time, I’ve become more and more puzzled about our healthcare system and how otherwise responsible human beings can tolerate the way that common behaviourial rules are suspended when you access healthcare.

In my role I am supposed to order people named ”patients” to behave the way that I or the ”science” believe is the right way to behave. At the same time, most medical practitioners know that their patients will not in fact behave the way recommended. Most studies on “compliance” with recommended treatment show that only 40-50% of patients actually follow therapy recommendations (WHO, 2003). This behaviour is most often a result of their conscious choice and does not arise from stupidity or ignorance. This mismatch is remarkable and the result is devastating to health as more than 50% of patients will be untreated for treatable or preventable diseases.

So, how did we get into this paradoxical situation?

To understand the modern healthcare system and its rules of behaviour, it is necessary to look back in time and try to understand how and why the system has developed. The healthcare system reflects society and is the result of the outlook and the values of citizens. From the beginning of the 16th century, the institutionalisation of health care started in monasteries. Naturally, the rules of behaviour (i.e. obedience and silence) were in accordance to monastic rules. The history of silence, and how we as humans can use the expectation of silence as a tool through which to rule over others, is fascinating. The monasteries aimed at helping people in need – but to get help you were expected to conform to the rules of the organisation.

In the early industrial period, and continuing into the post-world-war era, there was a widespread Western European political vision of the perfect society, in which blessed citizens would live happy and productive lives and where the state would look after all citizens. As a result of industrialization and urbanization, individuals who were not productive or who were a danger to public health (e.g. those suffering from tuberculosis or other infectious diseases or psychiatric conditions) were isolated in hospitals or sanatoria, which was a generally accepted approach. In Sweden this idealized state was named ”Folkhemmet” (”the people’s home”) but the fundamental ideas and dreams were quite uniform throughout Western Europe. Moreover, there was a belief that the State would help vulnerable groups by creating special enclaves designed to meet their specific needs.

The organisational models of the healthcare systems evolved by inspiration from the most advanced industrial model of the between-the-wars era, namely the car industry in Detroit. Therefore, healthcare was organized in departments and special units in order to focus upon production outputs instead of supporting people. The idea that the employees of the healthcare system should and could dictate how “patients” should behave is probably a consequence of the roles and rules arising from history, reinforced by the influence of an industry handling production outputs and seeking very hard to standardize. The term “patient” is revealing, as a problematic and stigmatizing construction. It is not connected to “patience” (although often you do need to be patient to put up with the wait for healthcare). It actually comes from the Greek word ”pathos” – ”to suffer” – which marks the people concerned as different from “us”, making a repressive approach more possible.

This first post-war era ended when politicians such as the UK’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher recognized that this vision of an ”idealised” society went beyond the bounds of possibility and that, even if it could be achieved, this would only be at the price of an intolerable repressiveness towards individuals. What politicians like Thatcher realized (I believe) is that society actually is a conglomeration of individuals. This led inevitably to marketing the ideas of individualisation and personalisation.

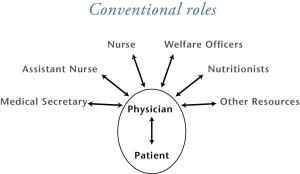

However, this led to many health care workers getting stuck in an antiquated system with an extremely conservative structure. The reason why it has been so hard to change is difficult to understand. However, I think that one of the key reasons is that it is a very hierarchical system and that people at the top of the system are comfortable with it, so they do not have much motivation to change. Furthermore, it is becoming increasingly obvious that modern public management systems are focusing on processes instead of results, which preserves the current system.

How can we change healthcare towards a more human system?

We have to accept that the behavioural rules underlying the traditional system are unacceptable and out of line with citizens’ expectations in the 20th century. So we need to redesign the system. To do this we will have to change the way we think about healthcare. In particular, we need to develop an alternative approach, harnessing the skills and capabilities of human beings instead of continuing to use repressive approaches. We have to incorporate principles of co-design and co-production into how we think and interact – with staff, clients and their families, friends and networks.

We have to accept that the behavioural rules underlying the traditional system are unacceptable and out of line with citizens’ expectations in the 20th century. So we need to redesign the system. To do this we will have to change the way we think about healthcare. In particular, we need to develop an alternative approach, harnessing the skills and capabilities of human beings instead of continuing to use repressive approaches. We have to incorporate principles of co-design and co-production into how we think and interact – with staff, clients and their families, friends and networks.

This is how I started to transform my ward at in the Highland Hospital in Eksjö hospital in 2001 as described in the Governance International case study.

One important driver of co-productive forms of behavior in healthcare may be greater transparency. Since we have moved to giving patients a much greater understanding of their own conditions, and how to interpret all of the information which we have on how their condition is progressing, we have had great improvements in our results. New ways of reinforcing this are now becoming available. For example, in the US and Sweden the rules are now changing so that patients have internet access to their own health record in order to help patients make proper choices. In the future, patients may even have the opportunity to add their own notes to health records which will open new possibilities.

Fundamentally this is a political issue, the basic question is how to let individuals take control of their own lives in a way that is in accordance with the 20th century.

Jörgen Tholstrup is the Chief Medical Officer at the Highland District County Hospital in Eksjö, Sweden. Until December 2013 he was the head of the gastroenterology unit in that hospital.