Calum Webb (University of Sheffield) and Paul Bywaters (Huddersfield University)

Children’s and Young Peoples’ Services, encapsulating children’s centres, safeguarding and social work, family support, services associated with looked after children, often totals nearly £10 billion of spending annually. Despite this, limited attention is paid to how these funds are spent, and much less is known about how such spending has changed over time. Has spending increased or decreased under austerity? Have budgets for front-line services for some of the most vulnerable and voiceless members of society – children at risk of abuse and neglect – been protected, as is often claimed, or axed, in the face of the rising strain placed on local government finances? Where cuts have been made to cope with reduced budgets, where have they fallen? Have cuts to children’s services been greater in more deprived local authorities, as previous research by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has indicated, further disadvantaging children from poorer communities and with greater needs?

The contradictory findings from government departments does not inspire confidence in their ability to answer any of these questions convincingly. A 2016 report from the National Audit Office concluded that expenditure on children’s services had risen by approximately 12 per cent between 2012 and 2015. This report, however, only looks at a sum of between £1.6 billion and £1.8 billion, and we had no luck replicating this figure – not with any combination of categories or adjustments for inflation.

A more recent report published by the Department for Education came to fundamentally different conclusions, namely that total expenditure had fallen by 9 per cent between 2010 and 2016, and that between 2012 and 2015, the same period covered by the NAO report, spending had reduced from £9.2 billion to £8.9 billion, a 3 per cent reduction.

The problem is partly down to the quality of the data – the inconsistency of categories between years prevents any meaningful long term comparisons of very specific spending areas. A few of the broader spending categories are fairly stable over time, namely spending on looked after children and spending on safeguarding, and the remainder of categories can loosely be considered ‘preventative’ or ‘early intervention’ services. These are the Sure Start centres or family support services that are intended to address the difficulties children in need may face before these problems develop to the point that they require more drastic interventions.

The second major problem with the official reports is the tendency to only focus on changes in the total national levels of expenditure, rather than focusing on what has been happening on a local authority level. All it takes is a few of the larger local authorities, the ‘big spenders’, to see an increase to dwarf many negative trends in smaller local authorities. This approach therefore doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality for children across England.

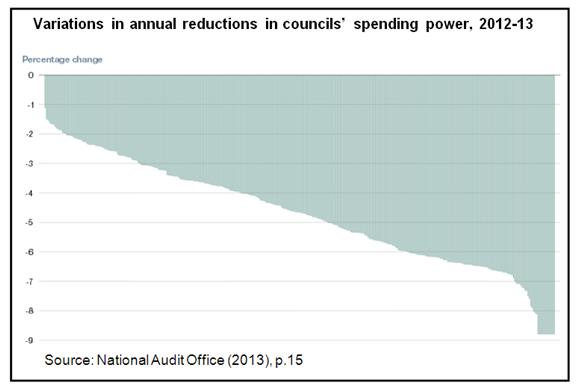

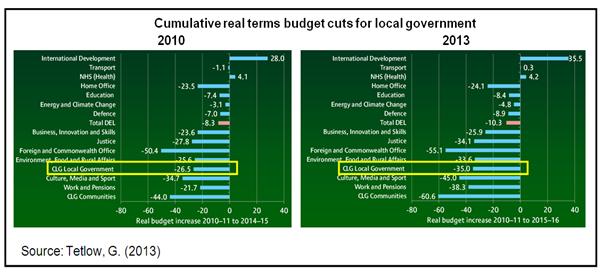

When we looked at expenditure after taking these things into account we found very clear patterns. The most deprived 20 per cent of local authorities had seen reductions in spending of 25 per cent, whereas the least deprived 20 per cent have had cuts of 4 or 5 per cent. When we split local authorities into three equally sized groups of 50 (the City of London and Isles of Scilly LAs are excluded as outliers), based on their deprivation scores, we found significant differences in the expenditure trends: rapid rundowns of expenditure per child in the 50 most deprived local authorities, less extreme cuts for the 50 ‘middle’ deprived local authorities, and far less severe cuts for the 50 least deprived local authorities. This is in part due to the indiscriminate way in which austerity measures have been introduced, without attention to the fact that more deprived local authorities typically have higher spending per child to meet greater levels of more complex needs. This means a hypothetical 10 per cent cut in Middlesbrough is going to result in a much bigger loss of £-per-child than a 10 per cent cut in Wokingham.

What’s more is that the share of spending across the different services has changed substantially, mirroring patterns in social work practice more broadly. The share of spending has shifted away from the aforementioned preventative and support services in favour of maintaining the share of safeguarding spending and increasing the share of looked after children spending. On average, local authorities spent around 46 per cent of their children’s services budget on more prevention focused services in 2010-11. By 2014-15 this had fallen to only 33.5 per cent. This has been fairly universal across all local authorities, but slightly more extreme in the most deprived third, and is best seen visually.

We don’t know completely what impact this will have on the lives of children, but we do know that since 2010 there has been evidence of an increase in demand for children’s social services; with average Looked After Children rates increasing from 57.5 children per 10,000 in 2010-11 to 62 children per 10,000 in 2014-15, and the number of children in the population rising by approximately 750,000 since 2010. Furthermore, this population increase has been largely concentrated in the most deprived local authorities (12%) compared to the least deprived local authorities (4%), meaning stable intervention rates – such as rates of children in care – actually represent a substantial increase in workload for practitioners. This is just one part of a complex picture of disadvantage that children living in poverty face. What we do know is that there needs to be a clear commitment to improving the quality and detail of the data that is collected about expenditure and deprivation because, as Ofsted’s Annual Report has acknowledged, there is a link between this and the quality of the services children receive across the country.

The research presented here was funded by the Nuffield Foundation and is part of the Child Welfare Inequalities Project and will be published in Local Government Studies in February 2018. Evidence from the project is being presented to an APPG for Children on the 7th February 2018.

Calum Webb is an ESRC White Rose postgraduate research student at the University of Sheffield’s Department of Sociological Studies. He has recently contributed to the ESRC funded research project ‘Developing a Policy Learning Tool for Anti-Poverty Policy Design and Assessment’ and the Nuffield Foundation funded ‘Child Welfare Inequalities Project’. His PhD research investigates approaches to the longitudinal measurement of multidimensional poverty. Calum tweets using @cjrwebb

Calum Webb is an ESRC White Rose postgraduate research student at the University of Sheffield’s Department of Sociological Studies. He has recently contributed to the ESRC funded research project ‘Developing a Policy Learning Tool for Anti-Poverty Policy Design and Assessment’ and the Nuffield Foundation funded ‘Child Welfare Inequalities Project’. His PhD research investigates approaches to the longitudinal measurement of multidimensional poverty. Calum tweets using @cjrwebb

Paul Bywaters is Professor of Social Work at Huddersfield University working in the Centre for Applied Childhood, Youth and Family Research. He has led a series of research projects funded by the Nuffield Foundation and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation which have examined inequalities in the incidence of and responses to child abuse and neglect between and within the four UK countries. For more information can be found here. Paul tweets using @PaulBywaters

Paul Bywaters is Professor of Social Work at Huddersfield University working in the Centre for Applied Childhood, Youth and Family Research. He has led a series of research projects funded by the Nuffield Foundation and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation which have examined inequalities in the incidence of and responses to child abuse and neglect between and within the four UK countries. For more information can be found here. Paul tweets using @PaulBywaters