Chris Game

Next week is the last week of Hilary Term, or revision week at the end of Spring Term, as it’s known here at the UoB and most other universities who feel no great affinity to the probably inappropriately named 4th Century St Hilarius of Poitiers. Over the many years in which I lectured undergraduates, I used rather to like it: end of the course/module in sight, legitimate chance to share and spread gossip about approaching local elections, lecture attendances boosted by students desperate for exam hints. Plus, nowadays, plenty of discussion-prompting visual aids – one of which is the pretext for this blog.

SIGOMA is not – disappointingly perhaps – an African hip-hop band, but less catchily the Special Interest Group of Municipal Authorities (outside London) within the Local Government Association. Yes, even the brackets are part of the full name – which has to convey that its 45-council membership comprises most major urban authorities in the North, some in the Midlands, plus the ‘South Coast regions’ of Plymouth and Portsmouth. The 45, claim SIGOMA, share similar characteristics and can therefore advantageously speak with a collective voice – moreover, with one that, particularly following the Coalition’s changes to the local government funding system, needs to be distinctive from that of the LGA with its responsibility for somehow representing the interests of all its 400+ member authorities.

These funding changes, argues SIGOMA, are so divisive, and their impacts so damaging to areas with characteristics like those of its members, that they threaten to set region against region in the manner of – well, Game of Thrones. As even non-followers of the popular TV series may be aware, the US fantasy drama chronicles the violent dynastic struggles for control of the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros. SIGOMA’s spoof YouTube video is Game of Cuts – Winter is Coming for Councils – and, at under 2½ minutes to Game of Thrones’ soon-to-be-five seasons, it’s inevitably (even) less subtle.

The Sean Bean character, Lord ‘Ned’ Starp, Warden of the North (possibly Steve Houghton, Leader of Barnsley MBC, SIGOMA’s administrative base?) and his mate from the Coastal Ports, protest that “our people are already on their knees … the sick have no one to care for them, and our children nowhere to read …”, while the spokesperson for “the hamlets of Bucks and Berks” remonstrates that they too are suffering, with “not enough funding to keep our tables supplied with swan and game”. But sadistic Queen Cersei of the South and her incest-conceived son, King Joffrey, are unmoved: “All the regions have had to make their sacrifices. The money has been spread evenly and you will cope, for the sake of the Seven Kingdoms”.

Doubtless, Local Government Minister Kris Hopkins’ family arrangements are altogether more conventional, but his presentation of the 2015-16 finance settlement last December suggests similarly briefed scriptwriters:

“The local government settlement is fair to all parts of the country – north and south, rural and urban, city and shire – therefore every council should be able to deliver sensible savings while protecting frontline services for local taxpayers … Those facing the highest demand for services continue to receive substantially more funding. For example, Middlesbrough has a spending power per household of £2,441 which is £871 more than the £1,570 per household in Windsor and Maidenhead.”

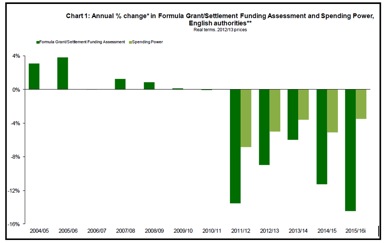

As noted in my recent blog assessing that settlement this has been the standard – and increasingly disingenuous – government line for the past five years. That blog, though, was largely about ministers’ ploy – what one might call the ‘spending power sleight of hand’ – to mislead the media and public from the outset about the true severity of their cuts to the funding of the local government sector as a whole. SIGOMA’s current campaign – Protecting Vital Services – is about the discriminatory distribution of the cuts within the sector, and particularly the impact of the funding changes since 2013-14, which cumulatively have switched the determination of government funding from assessed needs formulae to councils’ tax-raising capacity.

The big change was the introduction of the Business Rates Reduction Scheme (BRRS). It was cautiously welcomed by local government for its devolutionary principle, but SIGOMA-profile authorities were immediately concerned that, as BRRS funding increased and Revenue Support Grant (RSG) correspondingly decreased, the big gainers would inevitably be already prosperous authorities with higher rate-raising capacities, and the gap between them and the less well-off with the highest demand for services would continue to grow.

The New Homes Bonus Scheme (NHB) story was not dissimilar. It was launched in 2011-12 to incentivise local authorities to grant planning permissions for new homes and bring empty properties back into use. For each additional home they would receive for six years an annual bonus payment equal to the council tax generated – from the government’s own funding. Again, it was cautiously welcomed, although it was obvious that authorities with higher banded housing would be the bigger beneficiaries. But no sooner was it established than the government funding bit switched to a top-slicing of RSG, and again poorer authorities have been absolute, rather than just relative, losers.

The Council Tax Freeze Grant was slightly different, in being from the beginning a disadvantageous bribe to councils to cut their spending, but its relevance in this context is that it too is top-sliced from RSG. Put just these three policies together over the three most recent finance settlements, and RSG – the principal source of central government funding of non-schools revenue expenditure and traditionally the mechanism for recognizing councils’ differing resource needs – has shrunk as a proportion of local government funding by over 5% a year.

SIGOMA calculates that over just these three years authorities with higher grant dependency and greater formula share in RSG have lost proportionately twice as much (around 20%) as those with more buoyant rates bases and greater protection within RSG (around 10%).

Incidentally, further confirmations of deprived areas suffering most harshly from the government’s cuts have been produced over the past few weeks alone in an Institute for Fiscal Studies Briefing Note, by the Association of North East Councils, and, most tellingly, in evidence from the DCLG itself in the Public Accounts Committee’s report on the Financial Sustainability of Local Authorities (paras 8ff.).

Game of Cuts doesn’t go into the intricacies of RSG that SIGOMA’s Protecting Vital Services study does, confining itself to the billboard-style message that “Since 2010 local government in England has lost more than 40% of its core funding. Urban authorities, largely in the North and the Midlands, have lost the most money as a result of these cuts.” You don’t get SIGOMA’s proposed ‘fair and sustainable’ three-block future funding model either, but both productions, in their very contrasting ways, are worth a look – even if you don’t have a bunch of students to entertain.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

With apologies for the length of this blog, that’s what this particular local-central argument is fundamentally about – a little more than just the niceties of statistical presentation.

With apologies for the length of this blog, that’s what this particular local-central argument is fundamentally about – a little more than just the niceties of statistical presentation.