Chris Game

Remember the 2000 US Presidential election, the seemingly endless Florida recounts, and how we mocked an electoral system that took 35 days to produce a winner? Well, it’s now over eight times as long – 287 days and counting – since last May’s Welsh local elections. Yet, with a tad less riding on the result, one of the winning candidates in Denbighshire County Council’s Prestatyn North ward has still to take his seat. And if that doesn’t signify a busted system, utterly unfit for purpose, it’s hard to imagine what might.

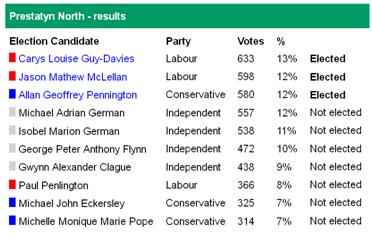

It’s a story that started as mildly amusing, passed through farcical around October, and is now just an all-round total embarrassment. It’s most easily understood by seeing the election result as announced by the Returning Officer (RO), from which you may also be able to guess the problem.

Source: Denbighshire County Council

Yes, one of the Conservative candidates and one of Labour’s have quite similar surnames, and, while many electors certainly will have split their three votes between candidates of different parties, a Labour-Conservative split result of these dimensions looks, to say the least, odd. It was. Without getting too nerdy, Pennington (Con) had been credited with a share of the votes of those who voted en bloc for all three Labour candidates, and Penlington (remember: L for Labour) with the rather smaller share of the ‘straight slate’ Conservative ballots. In electoral administration jargon, there was a screw-up.

At which point, I would say two things. First, such inept-but-innocent counting screw-ups happen more often, and with more significant consequences, than you might think. In Broxtowe (Notts) last year, the names of a Lib Dem husband and wife were transposed in copying them from the corresponding numbers list to the count summary sheet, and the wife was officially declared elected, despite polling 21 fewer votes than her now officially defeated husband.

Waltham Forest in 2010 managed a mix of Broxtowe and Prestatyn. In copying Labour’s en bloc votes, Labour’s three candidates each received 2,451 instead of 1,451 – sufficient to enable the party’s third-placed candidate to be elected, rather than the leading Lib Dem. And in a much publicised case in Birmingham’s Kingstanding ward in 2006, a BNP candidate was elected, having been gifted an extra 981 votes in a double-counting of all those ballot papers on which electors split their two votes between candidates of different parties.

With these Waltham Forest and Birmingham cases in mind, my second point is that the numbers of votes involved in these screw-ups can be not only large, but beyond the bounds of arithmetical possibility. The combined votes of all candidates – announced, it’s worth emphasising, by the ROs, after recounts rigorously scrutinised by candidates and agents of all parties – totalled respectively 1,397 and 2,367 more than would have been possible, even if every voter completing a ballot paper had used every vote available to them.

This is the bit that, to me anyway, passeth all understanding. Can candidates have so little idea of how the election’s gone that they’re not curious about why their vote is 50% higher than they might have expected? And how come none of these key actors involved in the counts could do even simple addition?

Whatever the explanation, once a candidate is declared elected, these essentially innocent administrative errors immediately become seriously costly. It might seem convenient, if an embarrassed RO were able publicly to admit that “Oops, I made a boo-boo. Can we all go back five minutes?” Sadly, election law and convention decree that this is not on. In the UK the only way to challenge a declared result is legally, and expensively, for a miffed candidate or elector to issue an election petition within three weeks of the election, pay the £465 fee, and also ‘give security’ for all relevant costs arising – up to £5,000 in a parliamentary election, £2,500 in a local. No security, no petition.

Here’s where the trouble starts and where fundamental reform is decades overdue. A robust procedure for challenging the result, whether on the grounds of innocent administrative error or deliberate fraudulent practice, is a vital part of any sound electoral system. It should have the attributes of ARTESSA, being accessible, rational, transparent, efficient, straightforward, swift and affordable. Our petition procedure today, little changed from that set out in the 1868 Parliamentary Elections Act to deal with bribery, treating, personation, undue influence and other corrupt practices, is none of these, as Prestatyn North’s hapless Paul Penlington is still discovering the hard way.

That there had been a substantial counting error was first realised apparently by the RO and Council Chief Executive. Labour, both candidate and party, were slow to protest – one suggested reason being that, without knowing the exact number of wrongly assigned votes, there was the real possibility of a correction letting in not Penlington, but the fourth-placed Mike German, a one-time Labour councillor before he defected to help form the Democratic Alliance of Wales – than whom even a usurping Conservative might be marginally preferable. Eventually, however, a petition was issued, to have the votes recounted and the result overturned.

Despite the Council having admitted from the outset its “fundamental error”, it still took until late July for the jury-less High Court to authorise a recount, and a further three months for that count to take place in, for some reason, London. Unhurried, certainly, but only now does the tale become truly incredible.

The result of a recount can only be officially announced and accepted by a special two-judge election court, which took nearly a further three months to convene – again in London. Only on January 23rd, therefore, were the correct figures finally declared – Penlington 606, Pennington 341 – and the original result overturned.

You wouldn’t, by now, expect the ruling to come into effect immediately, and of course it didn’t. The duly elected Councillor Penlington should, though, have taken his seat a week later – had former-Councillor Pennington not decided that the loss of his allowances would put his “livelihood at stake”, refused to give up his seat, and objected in writing to the court’s decision. Incidentally, legal costs, awarded against the Returning Officer, were estimated at this point to have passed £20,000, with the clock presumably still ticking.

There is so much wrong here that, even given the space, it would be hard to know where to start: the time, the cost, the arcane and detrimental procedures, the irrationality and inflexibility? Why the great rush to issue a petition, when the judicial process meanders as it pleases? Why can one elector challenge a parliamentary election, while four are required for a local election? Why can’t a Returning Officer or a political party initiate a petition? And so much more – most now thankfully documented in the Electoral Commission’s excellent report, Challenging Elections in the UK.

Prestatyn North may be just a quirky contemporary footnote, but it does illustrate one key aspect of the problem. The petition procedure was designed to deal with 19th Century corrupt practices in parliamentary elections. Its requirement today is to deal with 21st Century corrupt practices, and more frequently with innocent errors and administrative misjudgements, in local government elections – for which it is hopelessly ill-equipped.

There were 52 parliamentary petitions tried in 1868 alone, all dealing with alleged malpractice. Since 1929, however, there have been just 11, including six from Northern Ireland and three from the single constituency of Fermanagh & South Tyrone. They sometimes make headlines – the then Anthony Wedgwood Benn’s disqualification as a Peer in 1961, ex-Labour minister Phil Woolas’s disqualification in 2010 for making false statements about his Lib Dem opponent – but they’re rare.

Local government election petitions are not rare. Since 1997, at least 44 from principal councils have gone to trial, plenty more from town and parish councils, and still more have been withdrawn before trial, usually due to lack of funds. Of the 16 in the past five years, two (both subsequently withdrawn) claimed a candidate was disqualified to stand, and three alleged corrupt or illegal practices committed by or on behalf of a candidate.

The remaining 11 concerned actions by electoral officials: either administrative Prestatyn-type errors or process decisions causing the election not to have been conducted ‘substantially in accordance’ with the rules – actions, in short, wholly different from those with which petitions were designed to deal.

The Law Commission has embarked on a comprehensive review of electoral law, aimed ambitiously at collating and reforming the existing morass of primary and secondary legislation into something more coherent, and conceivably even a single modular UK Electoral Act. It’s still in its early stages, and its members may hope that when they eventually reach ‘Challenging the election result’, they’ll be almost there. The sorry saga of Prestatyn should remind them that they won’t be.

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.