Chris Game

One thing I’d expect most of this blog’s readers broadly to agree on is that UK ‘local’ government should really be given what grammarians call doubt quotes. It ceased long ago to be meaningfully local, decades before the next generation of county-based levelling-up deals.

So, I thought, where better to start this International Women’s Day (IWD) overview of women’s elected presence in local and central governance than at the other extreme: Barbuda, the alphabetically secondary part of Antigua and Barbuda, the Caribbean country comprising these two Leeward Islands plus several enticingly named even smaller ones: Great Bird, Prickly Pear, etc.

Constitutionally almost just like us, A & B is a unitary, parliamentary, representative democratic monarchy: a two-House Parliament, with only the lower House directly elected, but Labour faring rather better than they have done here lately. Here’s the thing, though. The two main islands are wildly unbalanced – Antigua with over 97% of the nearly 100,000 population, Barbuda barely 2%. Yet Barbuda is the one, for 45 years now, with the local democratic smarts: its directly elected Barbuda Council.

The island of Antigua is run by – yes, you guessed – ‘The Ministry’; in this case MESYGA, the Ministry of Education, Sports, Youth and Gender Affairs. Barbuda has not only its elected 11-member Council, but, as you’ll see from its Barbudaful website, a majority of women members and a woman Chair.

Such councils anywhere are rare, which is why – I could sense you wondering – Barbuda’s is deservedly up front on IWD, or in UoB’s case the start of International Women’s Month. And the remainder of this blog will draw on some of the other amassment of data in surely THE most fitting sourcebook for the day. Entitled, with needless modesty, a ‘Working Paper’, it’s UN Women’s Working Women’s Representation in Local Government: A Global Analysis, authored chiefly by Ionica Berevoescu and Julie Ballington, published December 2021 – and it’s a treasure trove.

The overview of new local-level data that ideally should constitute the core of this blog is inevitably pretty summary, but needs to be made even more so by at least a brief reference to the subject’s overall political context and importance. Women’s rights to equal political participation at all levels of government have for the past quarter-century been variously asserted, affirmed, and endorsed in proclamations of international goals, most importantly in the 2030 UN Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – Target 5.5 being to “ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life” (emphasis added).

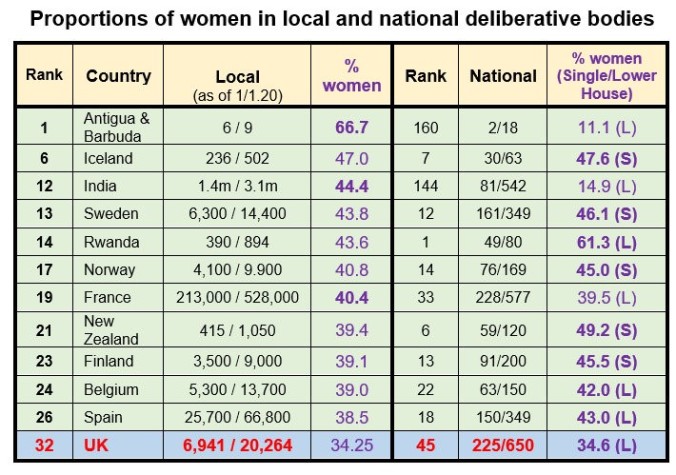

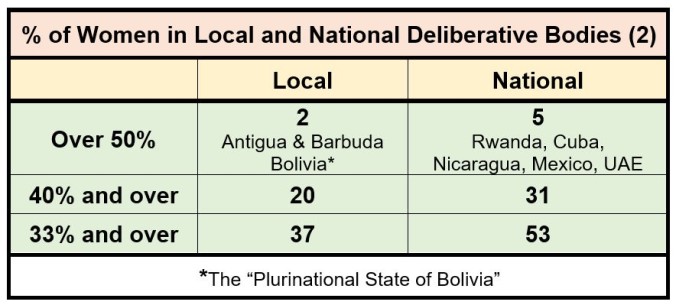

It’s that new indicator – extended to women’s representation in the world’s local governments, or at least 133 of them in early 2020 – that this blog was going to be primarily about. It got kind of overtaken, though, by the even bigger question: Are women worldwide, as has long been the case in Britain, better represented in local than in national governments?

Given the nature of local governments’ usually major service responsibilities and expenditures, my personal feeling was that it would be rather regrettable if they weren’t – the more so if I was wrong on the UK figures, and, instead of simply getting closer by the year, they could be shown statistically finally to have crossed over.

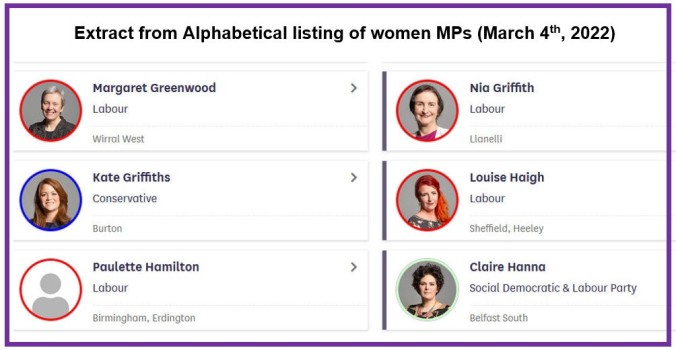

SPOILER ALERT! However, since, and probably even before, last Thursday’s Birmingham Erdington parliamentary by-election – in which Labour’s Paulette Hamilton became the seventh woman victor in this Parliament’s eight by-elections and the fifth to replace a male predecessor, bringing the total of women MPs to a record, and statistically significant, 225 – I WAS wrong.

Here’s how. Thanks to the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s annual tabulations, we’ve been able to track that part of the international picture for decades. In the 1990s the top women-friendly countries were notably Euro-dominated, though with no help from us. In !997, for instance, the only five Lower Houses internationally to have more than 30% women memberships were Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands. New Zealand, the Seychelles, Argentina and Mozambique were trying, but the UK was down in an embarrassing 50th place and unable to manage even double figures. Ahead, admittedly, of France and Greece, but that was about it.

Ten years on, thanks considerably to the arrival of variously legislated or voluntary gender quotas, the overall picture had improved, and Rwanda had crashed the 50% barrier, with 45 (56%) women in its 80-seat Chamber of Deputies. Cuba and Argentina were over 40% … and the UK, though still just ahead of France, was down to 60th, struggling now to reach 20%.

Today – or, more precisely, in last month’s IPU Parline rankings – the global picture has become more variegated still. The top 15, with around 45% or more women, currently comprise five countries from each of Europe (Iceland, Andorra, Sweden, Finland, Norway) and Latin America (Cuba, Nicaragua, Mexico, Bolivia, Argentina), two African (Rwanda, of course, and South Africa) and one each from Asia (United Arab Republic), Australasia (New Zealand), and the Caribbean (Grenada).

And the UK? Up to a hardly glorious 45th alongside Dominica – with just over the one in three, which at least is better than the House of Lords’ 28.6%.

So … the big question was: Is our local government today – still, as always hitherto – more gender representative than our national elected legislature?

As you may sense, I wasn’t bringing absolute researcher detachment to this exercise. It was posed in the hope/expectation that it would prove to be what Latin scholars call a ‘nonne’ or affirmative question, expecting the answer ‘Yes.’ Of course there’d be a higher proportion of women councillors than women MPs – wouldn’t there?

I knew the 2019 General Election stats: 220 women MPs, including, obviously for the first time, majorities of both Labour and Lib Dem Members. Congrats, obviously, to them, but, with the Conservatives’ massive majority comprising under a quarter of women, local government would still have at least a narrow percentage lead – wouldn’t it?

But then began, as noted above, the striking trend of victorious women by-election candidates replacing former male MPs, and when Paulette Hamilton did her thing last Thursday, I was getting seriously nervous. 225/650 is 34.6%; rounded up becomes 35% – an all-time record, which is obviously a ‘good thing’, but worryingly close to what I reckoned the local government figure to be.

To cut a potentially tedious story short: if, as we relatively rarely do, we compare the whole of UK local government – as opposed to that of England, or sometimes England and Wales – it currently makes the decisive difference. For the first time, authoritative, genuinely compiled and comparable statistics showed there to be proportionately more women MPs than women councillors.

I shall now retire gracefully from this particular field of research and address something perhaps more rewarding – like whether being a plurinational, rather than merely multinational, state somehow boosts women’s electoral prospects.

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.