Dr Philip Whiteman

In English local government, the issuance of a section 114 notice is often perceived as a dire financial omen, signalling a council’s descent into insolvency. While financial stability is undoubtedly a cornerstone of effective governance, it is crucial to recognize that section 114 notices reveal more than just a precarious financial situation. They serve as a beacon, illuminating underlying issues that extend beyond the confines of spreadsheets and budget projections. Either way, the government’s Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DeLUHC) tends to respond with intervention and the imposition of commissioners to direct the authorities concerned.

The poor financial position of many authorities may be the direct result of years of underfunding by central government and we can expect many more councils to serve section 114 notices, but it would be improvident to assume there are no further underlying causes.

Nottingham City Council’s recent declaration of a section 114 is a clear indication that some authorities are simply folding due to a broken funding formula, but this is not the sole cause of failure in all cases. When looking at other authorities, alternative underlying causes are present. Further examples include:

- The BBC Panorama programme highlighted how Thurrock Council was rendered bankrupt following a series failed investments in a solar farm, highlighting disastrous procurement practices, lack of accountability, poor governance, and inappropriate delegations to officers.

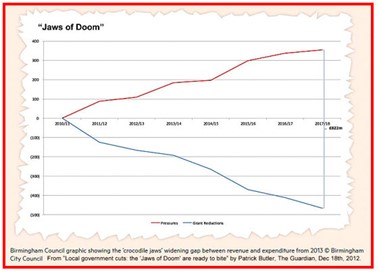

- Birmingham City Council’s problems did not emerge overnight and were a culmination of challenges created by a historic equal pay-claim and botched procurement a new IT system, Oracle. Underpinning this was poor financial planning, governance, accountability, and a failing internal culture.

- Woking Borough Council racked up a deficit of £1.2bn following the building and acquisition of major property portfolio. Against these investments, the authority had acquired loans from the Public Works Loan Board and other local authorities, accumulating debts that it could not service.

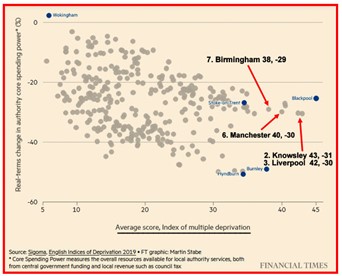

- Liverpool City Council’s woes are not confined to finances. Government commissioners were appointed to Liverpool City Council in June 2021 following a damning Best Value inspection by Max Caller CBE on matters pertaining to poor leadership, unacceptable performance, poor resource management and a failure to engage with citizens.

Government appointed commissioners tasked with overseeing councils in financial distress must adopt a holistic approach, venturing beyond the immediate financial crisis to uncover the root causes of the council’s predicament. This requires a comprehensive examination of the council’s structural framework, external environment, performance management and internal governance practices.

Structural Challenges: A Precarious Foundation

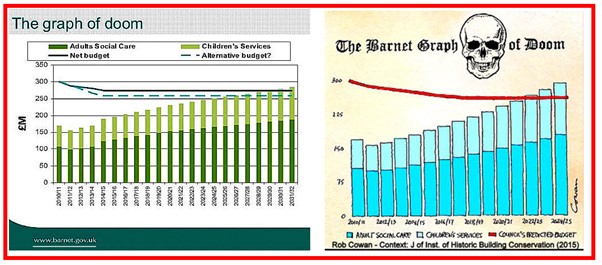

English local governments face a unique set of structural challenges that can hinder financial stability. The relentless rise in service demands, coupled with a funding system that often fails to keep pace, places immense pressure on council budgets. This mismatch between resources and responsibilities can lead to a cycle of overspending and financial strain.

Commissioners must delve into the council’s structural framework, assessing whether the current allocation of resources aligns with the council’s responsibilities. They must also evaluate the effectiveness of the council’s revenue-generating strategies, ensuring they are maximizing their income potential without overburdening residents.

External Factors: Navigating Turbulent Waters

Local governments are not immune to the vicissitudes of the external environment. Economic downturns, shifts in government policies, and natural disasters can all have a profound impact on a council’s finances. Commissioners must assess the council’s vulnerability to these external factors, evaluating its risk management strategies and identifying potential contingencies.

Internal Governance: Cultivating a Culture of Accountability

While structural challenges and external factors can undoubtedly contribute to financial distress, internal governance failures often play a pivotal role. Poor financial planning, inadequate risk assessment, and a lack of transparency and accountability can erode a council’s financial stability.

Commissioners must scrutinize the council’s internal governance practices, ensuring that financial decision-making is sound, risks are appropriately assessed, and accountability is firmly established. They must also foster a culture of transparency, empowering residents to hold their council accountable for its financial stewardship.

A Holistic Approach: Beyond the Financial Storm

In the aftermath of a section 114 notice, commissioners must resist the temptation to focus solely on immediate financial stabilization measures. Instead, they must adopt a holistic approach, addressing the underlying structural, external, and governance issues that contributed to the council’s financial crisis.

By adopting a comprehensive view, commissioners can guide councils towards long-term financial stability, enabling them to deliver essential services to their communities without succumbing to the pressures of insolvency. Only by addressing the root causes of financial distress can we ensure that section 114 notices no longer serve as mere harbingers of financial doom, but rather as catalysts for positive transformation.

Speculating on further interventions

Speculation is precisely that. Estimates vary widely in terms of how many further councils are anticipated declare section 114 notices, but a clear signal of further failures exists:

- In July 2023, ITV News cited a leaked DeLUHC document which estimated at least 26 bankruptcies over the next two years.

- The Institute of Government has estimated that 10% of councils are at risk over the next two years.

- The Special Interest Group of Municipal Authorities (SIGOMA), a representative body for 47 municipal authorities, published a survey in June 2023 which showed that five of their members were at risk.

- A Local Government Association Survey conducted in November 2023 revealed that almost one in five local authority leaders and chief executives believe that their authority may have to declare a section 114 notice.

Whilst estimates vary, there is evidence that further authorities will become vulnerable to government intervention via the imposition of DELUHP appointed commissioners. This raises a final question; can the predicted number of authorities realistically be serviced?