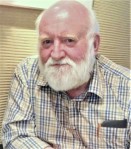

Cllr. Ketan Sheth

Public Health is important: it prolongs life. A fundamental quality of Public Health is its preventative nature; prevention is far more effective and far less expensive than cure. Public Health is important because we are constantly striving to close the inequality gap between people and encourage equal opportunities for children, all ethnicities and genders. Health is a human right and we should be ensuring no one is disadvantaged, regardless of their background, their ethnicity or where they live. Becoming the voice for people who have no voice is our collective duty. Simply put, our influence on the improvement of someone’s health is a fundamental act of kindness.

Poor housing and living environments cause or contribute to many preventable diseases, such as respiratory, nervous system and cardiovascular diseases and cancer. An unsatisfactory home environment, with air and noise pollution, lack of green spaces, lack of personal space, poor ventilation and mobility options, all pose health risks, and in part have contributed to the spread of Covid-19. The disparities in housing and public health within the BAME community have persisted for decades cannot be doubted, and is underscored by a raft of research over the past six decades as well as highlighted by the recent analysis of the impact of Covid -19. The death rate among British black Africans and British Pakistanis from coronavirus in English hospitals is more than 2.5 times that of the white population.

What are the possible reasons? A third of all working-age Black Africans are employed in key worker roles, much more than the share of the White British population. Additionally Pakistani, Indian and Black African men are respectively 90%, 150% and 310% more likely to work in healthcare than white British men. While cultural practices and genetics have been mooted as possible explanations for the disparities, higher levels of social deprivation, particularly poor housing may be part of the cause, and that some ethnic groups look more likely than others to suffer economically from the lockdown.

Homelessness has grown in BAME communities, from 18% to 36% over the last two decades – double the presence of ethnic minorities in the population. BAME households are also far more likely to live in overcrowded, inadequate or fuel poor housing. What’s more, around a quarter of BAME households live in the oldest pre-1919 built homes. And their homes less often include safety features such as fire alarms, which is striking given the recent Grenfell Tower tragedy. Over-concentration of BAME households in the

neighbourhoods in London, linked to poor housing conditions and lower economic status all ensure negative impacts on health, all of which means lower life expectancy. The roll-out of Universal Credit is having greater effects on the living standards of BAME people since a larger percentage experience poverty, receive benefits and tax credits, and live in large families.

Larger household size also means that ethnic minorities are far more vulnerable to housing displacement because of the Bedroom Tax or subject to financial penalties if they do not move to a smaller home.

These stark facts, sharply bring to our attention the health, social and economic inequalities among our minority ethnic community, all of which are critical to understanding why some ethnic minority groups are bearing the brunt of Covid-19. In this time of reflection, it is not enough to observe; we must think about what more we can do, right now, to reduce the health, housing and economic vulnerabilities that our BAME communities are much more exposed to in these fragile times. Let’s act and prolong life together, as a flourishing community.

Cllr. Ketan Sheth is a Councillor for Tokyngton, Wembley in the London Borough of Brent. Ketan has been a councillor since 2010 and was appointed as Brent Council’s Chair of the Community and Wellbeing Scrutiny Committee in May 2016. Before his current appointment in 2016, he was the Chair of Planning, of Standards, and of the Licensing Committees. Ketan is a lawyer by profession and sits on a number of public bodies, including as the Lead Governor of Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust.