Clive Stevens

“You won’t find many of them”, people quip when I tell them the title of my PhD; and my riposte, “that’s why I asked councillors”. And I was right; interviews with 17 councillors across four parties have revealed over 2,000 examples. Conceptions include: equality, proportionality, equity, fair opportunity, market fairness, fair administrative process and more. These conceptions were collected during the semi-structured interviews based on four carefully crafted vignettes (case studies). Thematic coding assisted their allocation into eight broad types (Realms) along with sub-categories like reciprocity, merit and efficiency. Sometimes the councillor denied they were talking about fairness, but they were; a simple reframing, usually changing a point of view, clarified the analysis, for example, council efficiency can be reframed as value for money and thus fairness to the taxpayer.

My PhD can be likened to an exploration. With me, the explorer, finding snippets of theory from various academic sources each describing a type of fairness and sometimes disagreeing with another. Thus equipped, I ventured into the jungle, Bristol City Council, and witnessed, watched and registered actual conceptions coming from actual politicians. I returned relatively unscathed and after analysis discovered much that agreed with theory but also much else. I now have a clear report to deliver about the eight, strange, fairness-beasts that rule their Realms and what happens when they mix.

Combinations

The findings map out the Realms more accurately and show that in certain circumstances a combination of Realms can elicit quite strong responses. For example, in one vignette, six councillors wanted to request a breach of council-house regulations to allow a tenant to sublet her flat. Reasons varied, but many were drawn to the description of her disadvantage, escaping an abusive relationship, and were impressed that despite all her problems she had not only sought work but actually landed a job. “Respect” and “this is the type of person we should be helping” were two of many responses. However, an equal number of councillors were totally unimpressed and thought she should be served notice as per the tenancy.

Another vignette, about a large donation to the Children in Care Service, offered councillors three policy options. Eight wanted to make policy changes; and every one of those changes was based on making the choices fairer.

Fair Process or Outcome?

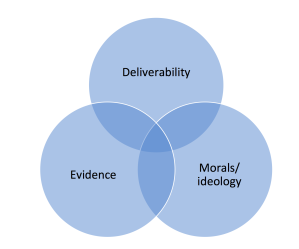

With this more reliable set of fairness definitions, the data can be analysed in many ways. For example, there is debate about whether fairness in Local Government should be about fair process or fair outcome, some arguing one way and some the other. I recall a council officer telling me that if a decision follows fair process from a fairly formulated policy, then it must be right whatever the outcome. But is that fair?

This data lets me measure the number of conceptions of fair process and the number of conceptions of fair outcome; there was little difference whether the councillors were male or female, new or experienced, and from different parties. But it did change and dramatically, if the councillor was or recently had been in a cabinet or committee chair position compared with backbench councillors. The latter group were much more interested in fairness of outcome. This is a finding from a qualitative study, so not definitive, but I’ve already had a number of conversations saying “that’s not surprising” each with suggested reasons. Perhaps a more rigorous study could be done.

Party Dogma?

Another question I’m asked is about the influence of parties. The interviews were conducted singly and confidentially; I hope I reached the councillors’ true views. One vignette asked them to come to a conclusion and vote based on their values, and then asked whether their vote might change if it were whipped. Many said they might change out of loyalty. Loyalty, like fairness, is a moral value and clearly quite powerful.

Wicked Problems

One of many potential uses is in understanding intractable “wicked” problems. These are made more wicked if there are value differences between the stakeholders. Fairness is a human value, so perhaps an understanding of fairness could assist in some small way to make headway with such problems that seem nowadays to be popping up everywhere.

What next?

I have just entered the final year; out of the jungle but not quite out of the woods, yet; there’s a lot of writing up to do, and then I’d like to use the findings and meet up with people interested in better understanding other councillors’ or parties’ values.

An ex-councillor in Bristol and author of the book on Local Government, After the Revolution, Clive followed up on politicians’ conceptions of fairness. He is now his final year of a PhD at the University of Bristol, interviews complete and writing it up. His personal blog site is: https://sageandonion.substack.com/