Stephen Jeffares

The FT’s Chris Giles recently wrote:

“Mark Carney Bank of England governor, has signalled that his policy of linking interest rates to the unemployment rate [Forward Guidance] will be buried less than six months after its birth…his big idea for monetary policy has bitten the dust” (FT, 24 January 2014).

This is not the first time in the last year we have heard reports of “big ideas” “biting the dust”. The same has been levelled at Cameron’s purported big idea in politics: The Big Society. How funny that sounds just a few months after thousands of policy actors were deliberately inserting Big Society terminology into their strategies, job descriptions and articles. A friend who recently attended a meeting at CLG told me that the last remnants of the Big Society team have now left their posts; organisationally, at least, the Big Society is dead.

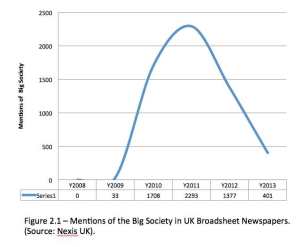

As the title suggests, and in a new book, I argue that Big Society lasted around a 1,000 days. That is rather neat, I admit. Wayne Parsons has argued that you need a sensitive measuring device to understand the death and termination of public policies, but as a starting point you can think about newspaper citations. Although a crude measure, this reveals the date when a policy idea first entered the public realm, the peak of discussion, and the point after which it is never uttered again.

It reminds me of Frazer’s description of how Saharan Tuareg tribes would up camp when somebody died, and never mention the deceased’s name ever again. Although government actors do not quite up camp, they shuffle around, renaming units and amending job titles, renewing websites and pulping documents. As for the newspapers, for a while they write of the policy’s death, of u-turns, and discuss hints of decline (as in the article above); more important is to focus on the point where they stop mentioning it – that is when the idea is dead. It is also a point in time seldom acknowledged.

So where does my 1,000 days come from? Well, counting citations in British Broadsheet newspapers (see Figure 2.1) you can see that in 2008 there were no mentions of the Big Society, a few hundred in 2009, great excitement by 2011, and just over one mention a day in 2013.

My prediction is that at some point in 2014 we will not speak of Big Society again – it will be the end.

But will we see anything on the scale of Big Society ever again? If Forward Guidance is anything to go by, it is quicker and easier than ever to discuss, endorse, but also critique and deride policy ideas. But it is also quicker and easier to coin and foster them too.

Some critics of the Big Society pointed to how many times it was relaunched, but like iPhones or Apps, we are in an age where we can release beta versions, test things out, get feedback and quickly offer updated bug fixes or new versions. We cannot measure the longevity of a policy idea by expectation alone – no, we can speculate about decline but it is not until the tribe up-sticks and moves to a new part of the desert, vowing never to mention its name again, that we can be sure that it is truly dead.

An earlier version of this blog appeared here 27 January 2014.

Stephen Jeffares is a Lecturer based in INLOGOV. His fellowship focuses on the role of ideas in the policy process and implications for methods. He is a specialist in Q methodology and other innovative methods to inform policy analysis. Stephen’s book, Interpreting Hashtag Politics: policy ideas in an era of social media, will be published by Palgrave in April 2014. Preorder or follow @srjeffares