Chris Game

A couple of years ago I wrote a blog about choropleth maps and the accuracy, or otherwise, of the UK’s locally compiled electoral registers, in which I indulgently referred to the University of Essex, and particularly its Department of Government’s late Professor Anthony King, thanks chiefly to whom, as a 1960s postgrad student, I first became interested in such abstruse matters.

For me those UoE years were transformative, as no doubt they were for countless successors, including two prominent MPs – former Commons Speaker, John Bercow, and current Home Secretary, Priti Patel – whom The Times somehow mixed up in Professor King’s obituary. Recounting King’s tale of the now well-known ex-student whose thesis had been “so bad I virtually had to rewrite it” … the student was incorrectly identified as Bercow … rather than Patel. Grovelling apologies ensued, and not inconsiderable mirth.

It’s a pleasing story, but I’d have struggled to justify raising it, were we not currently witnessing a further example of Patel’s either inability or refusal to grasp the workings of surely King’s specialist Mastermind subject: electoral systems. The Home Secretary, in reviewing the role of our 41 Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs), wants to replace from 2024 what she calls the “transferable system”, by which they – plus the Mayor of London and nine Combined Authority Mayors – are elected, with the ‘First-Past-The-Post’ (FPTP) system we use for MPs.

Patel offers several reasons. It is “in line with the government’s (2019) manifesto position in favour of FPTP”, creates “stronger and clearer local accountability”, and “reflects that transferable voting systems (her plural, my emphasis) were rejected by the British people in the 2011 nationwide referendum”. Plus presumably, though unmentioned, she reckons on balance it would benefit the Conservative Party.

None of her assertions are straightforwardly true; only, strictly speaking, the bit about voters rejecting the 2011 referendum question – by a certainly decisive 68%. But that referendum was about one particular system, the Alternative Vote (AV) – supported ironically by neither party in the Conservative-Lib Dem Coalition and rejected understandably by voters as a contribution to producing the more fairly elected and representative House of Commons that at least many hoped the long awaited referendum would be about. Nothing to do with electing powerful, high profile and individually accountable public officials.

Moreover, if referendums are important, in the 1998 one creating the Greater London Authority, London electors voted by 72% for a Mayor elected by the then novel, but much debated, Supplementary Vote system she wants to abolish for us all with no voter consultation at all.

Her ‘transferable voting systems’ is anyway a potentially misleading term that I doubt Professor King would have used. ‘Preferential’ better describes the several systems allowing voters to express their ordered preferences for a list of candidates.

Best known is probably the highly ‘voter-friendly’ Single Transferable Vote (STV), used in multi-member constituencies, as in Scottish and Northern Irish local elections, where there are two objectives. First, to elect perhaps more representative ‘slates’ of local councillors than our FPTP system produces, and ultimately to elect more community-representative councils (or parliaments) by greatly reducing the numbers of ‘wasted’ votes cast for losing candidates.

Voters rank-order as many candidates as they like. A ’quota’ is set, based on the numbers of seats to be filled and votes cast. Then, once a candidate reaches that quota, proportions of their ‘surplus’ votes are transferred to voters’ second and subsequent choices until all vacancies are filled.

By contrast, PCCs and Mayors, as even the Home Secretary will have noticed, are elected individually. So the relevant ‘preferential system’ here is the Supplementary Vote (SV), using ballot papers with two columns of voting boxes, enabling voters to X both their favouritest candidate and their second favourite.

If no candidate gets over half the first-column vote – as in 36 of the 40 contests in the 2016 PCC elections, all five London and roughly two-thirds of all mayoral elections to date – just the top two candidates continue to a run-off, and will probably have campaigned with that eventuality in mind.

If either your first- or second-choice candidate gets through, they get your run-off vote. The important consequence is that the winner – here, every elected and accountable PCC – can claim the legitimacy and authority of having secured a majority electoral mandate.

Under Patel’s preferred FPTP system, 229 of our serving MPs could be accused of having slunk into office on minority vote mandates of regularly under 40%. Personally, I’d feel slightly diffident, even as a Conservative MP, knowing both I and my party’s Government were elected on way short of majority votes. But for a PCC, daily exercising wide-ranging policing powers, it would be potentially undermining.

In our ‘local’ 2016 West Midlands election, the incumbent Labour PCC David Jamieson, seeking re-election, managed ‘only’ 49.88% of first-preference votes – fifth highest out of 40 English and Welsh contests, incidentally. But in the necessary second-round run-off against the Conservative, Les Jones, that was raised to a significantly weightier 63.4%.

The difference, and demonstrable majority electoral mandate, would be handy for an MP – but of genuine weight and almost daily importance for Police and Crime Commissioners, more than half of whom received under 40% of first-round votes.

Or, indeed, for elected mayors. I can’t but think West Midlands Conservative Mayor Andy Street feels considerably more comfortable being able to claim a 50.4% run-off victory over Labour’s Siôn Simon in 2017, as opposed to the 41.9% that would have given him a FPTP victory.

Time now, with a final paragraph already typed, for a very belated declaration of interest – personal and academic interest, that is – in an electoral system effectively invented, developed and, I’d argue, deployed effectively during my university teaching lifetime. I knew, at least distantly, both possible claimants to the SV’s invention, and, while I’m well aware of its limitations, I do believe it was and, after 20 years’ usage, is the best system realistically available for the election of mayors and PCCs.

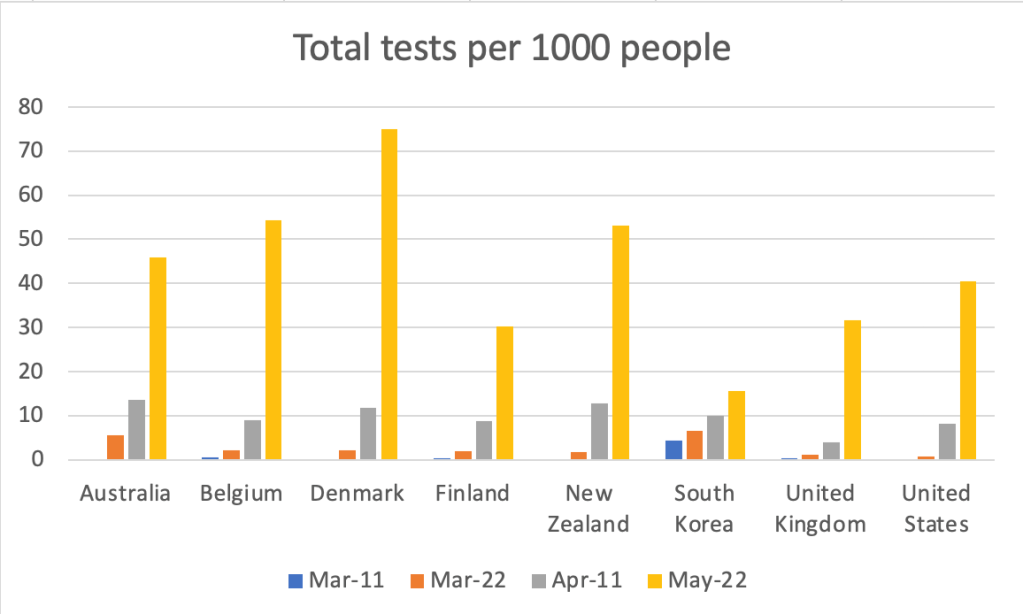

If you’re interested in more, try the excellent evaluative paper written at about the halfway point in that history – and so before the invention of PCCs – by Colin Rallings and colleagues. Pluses include a neat summary list of SV plus points (p.4), and some colourful and interesting bar charts.

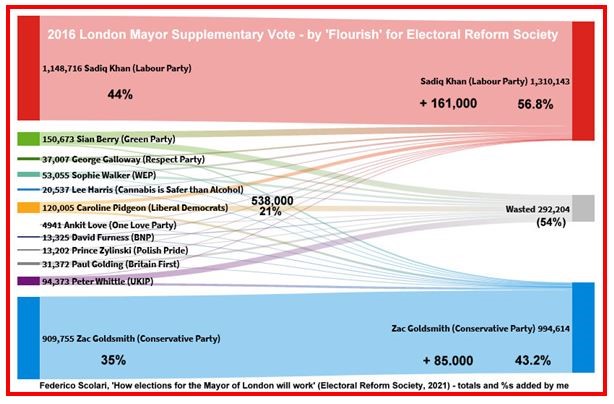

But nothing to rival the Electoral Reform Society’s recent effort: a creation of interactive beauty (the real thing, not my reproduction, obviously!), produced especially for this year’s elections, and showing for instance, as you’d possibly hypothesise, that first-choice Britain First and One Love Party voters split their second-choice votes proportionately really rather differently.

To conclude: my hope is that at least Patel’s intervention will prompt a few interesting campaign questions – I was going to type ‘hustings’, but I’m not sure we’re allowed those this time – for Conservative PCC and mayoral candidates. The 20 successful Conservative PCC candidates in 2016 averaged 36% of turnouts averaging under 25%, or under 10% of the registered electorates. Do they, I wonder, think election on their minority first-round votes alone – 11% of registered electors in Andy Street’s case – would give them the “stronger and clearer local accountability” Patel suggests it would?

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.