Chris Game

It seemed obvious from the outset that Gerry Adams’ arrest in connection with the 1972 murder of Jean McConville was a momentous event with potentially massive implications: long-term, short-term, north and south of the border. So I was slightly surprised the following morning to hear a Sinn Fein spokesperson, protesting about the timing of the arrest, highlight its impact specifically on the Northern Ireland local elections. Still, with the subject having been raised, I couldn’t help recalling the gerrymandering – or even Gerrymandering – controversies that were the chief reason why these elections on 22nd May for 11 new, larger and somewhat strengthened councils hadn’t taken place, as planned, in 2011.

The postponement was regrettable, given that the process of replacing the 1973 structure of 26 emasculated district councils had already been going on for years. The NI Executive had started a comprehensive review of NI public administration in 2002, shortly before its longest period of suspension. In 2005 Secretary of State Peter Hain announced a scheme for seven politically balanced ‘super-councils’ – three nationalist-controlled, three unionist, with Belfast and its politically mixed electorate swinging between the two – which did succeed in uniting most of the parties, except Sinn Fein, but unfortunately only in opposition to the whole idea.

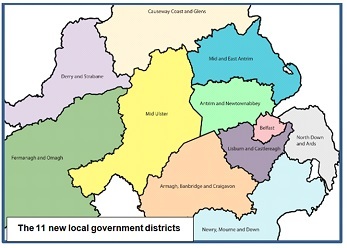

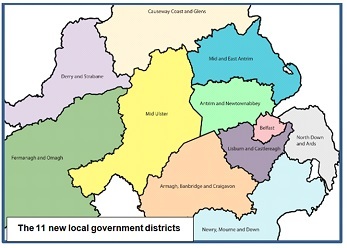

In 2008 the restored Executive split the difference between Sinn Fein and the unionists’ generally preferred 15-council structure by opting for 11, with a significant transfer of powers from central to local government, and the additional virtue of recognizable, if convoluted, place names, instead of vapid compass points: Armagh, Banbridge & Craigavon rather than ‘South’, and so on. The first elections would take place in May 2011 – or should have done, had it not been for the arguments over boundaries.

Traditional NI political wisdom has it that, if you want more than about, say, seven areas with roughly equal populations, no matter what number you choose, slightly more than half will have a unionist majority, and virtually all the remainder a nationalist majority. Changing demography is challenging this axiom, as may well be demonstrated in the compositions of the new councils. But, if the last elections to the old councils in 2011 had been contested on the new district boundaries, the best guesstimates are that the DUP would have been the largest party on six councils – those in the north and east, with the exceptions of Belfast and Newry, Mourne & Down – and Sinn Fein the largest party on the other five.

In one sense, these things have mattered less than might be supposed, partly because of councils’ limited powers, but also because a majority of them have long operated under similar responsibility- or power-sharing principles as the NI Assembly in, for example, their proportional allocation and rotation of committee places and chairmanships. No amount of responsibility-sharing, though, was able in 2012-13 to defuse the incendiary issue of flying the Union flag on town halls. Nor, as the details of the new districts emerged in 2008-09, did it prevent heated disputes about the proposed boundaries – particularly in, though certainly not confined to, Belfast, with its sheer size, centrality, and changing religious and political make-up.

Over the years the city’s electorate has shrunk and, like NI as a whole, has become steadily more nationalist. As a result, the once strongly Protestant council has become politically more balanced – the current make-up being 24 nationalists (Sinn Fein + SDLP), 21 unionists (Democratic, Ulster and Progressive), and 6 Alliance – although the unreformed ward structure means that it took roughly 1,700 votes to elect each nationalist member, against 1,500 for each unionist.

Almost any proposed configuration of larger reformed councils, therefore, would have been likely to produce a more nationalist Belfast. Predictably enough, though, when it appeared actually to do, so too did the headline accusations of gerrymandering, particularly over the extension of the city’s southern boundaries.

In fairness to the relevant sub-editors, at least they were using the provocative term in more or less its correct sense – manipulating electoral boundaries for partisan advantage – even though, as the map shows, no new improbably shaped districts, resembling salamanders or any other tetrapods, were involved. In fact, the map is possibly slightly misleading, for the main added areas – parts of Lisburn in the west and of Castlereagh in the east – are mostly quite densely populated and represent an increased population of over 50,000 or nearly one-fifth, bringing the city’s total to 334,000. There was undoubtedly an argument, on the basis of the existing built-up area, for pushing the boundaries significantly further in both directions and possibly also in the north – but not one with anything like enough political traction to gain it serious consideration.

With the religious affiliation of all the city’s wards and electoral areas being available down to decimal places – from 94%+ Protestant along the Shankhill and Crumlin Roads to 97%+ Catholic in the Upper and Lower Falls, perhaps the easiest way of describing the significance of the city’s actual expansion is in the same terms. The three wards that revert from Lisburn to Belfast – Poleglass, Twinbrook and Dunmurry – are between 80 and 95% Catholic and are also larger than the two transferred wards from Castlereagh – Gilnahirk and Tullycarnet – which are 81 to 86% Protestant. These two wards are situated due south of the Stormont Parliament (see the red star on the second map) and are part of the Belfast East Parliamentary constituency – as, a little further east along Upper Newtownards Road, are Dundonald and the Ballybeen housing estate. The 8,500 Ballybeen residents, however, who constitute three wards on their own, all overwhelmingly Protestant, are not being transferred.

The gerrymandering accusations, though, that contributed most to the three-year postponement of the introduction of the new councils were made across the other side of the city, in respect of the village of Dunmurry and the multi-hatted Edwin Poots: DUP Member of the NI Assembly, Minister (in 2009) for the Environment and responsible therefore for local government, and a longstanding member of Lisburn City Council.

In a nutshell, Councillor Poots claimed the administration of which Minister Poots was a member was ‘Gerrymandering’ to the advantage of Sinn Fein in Belfast. He proposed that said Minister Poots use his authority to make what Councillor Poots claimed would be a “modest adjustment” to the recommendations of the independent Local Government Boundary Commissioner and allow Dunmurry residents to remain within what would become a comfortably unionist Lisburn & Castlereagh – a proposal that, not surprisingly, some commentators also saw as gerrymandering.

Dunmurry was not the only boundary dispute, and boundaries were not the only matters of contention. But it was key sticking point. For, until Poots and his unionist colleagues eventually backed down, there could be no final settlement of district boundaries, and no progression to the determination of ward boundaries or, unique to NI because of the requirements of proportional representation, to the grouping of wards into District Electoral Areas. In the end it seemed to come as no great surprise when in June 2010 it was announced that the 2011 local elections would be to the existing authorities – which is perhaps itself unsurprising in a state whose very existence, many would say, is a product of gerrymandering.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.