Chris Game

You probably caught at least something of the Commons ‘cladding’ debate last Monday (1st Feb), and almost certainly some of this week’s fallout. Called by Labour on one of its designated ‘Opposition Days’, the debate sought “urgent” Government action to end the scandal of lease-holding flat owners, living in unsafe, unsaleable, uninsurable properties, being forced to pay unaffordable sums of money for the removal of flammable cladding.

And, if 43+ months after the Grenfell Tower tragedy qualifies as “urgent”, we finally got it this Wednesday, in the form of a statement from Robert Jenrick, Secretary of State for the whole thing – Housing, Communities and Local Government.

Important as that statement obviously is, neither its content nor even its questionable squareability with the PM’s most recent pledge that “no leaseholder should have to pay for the unaffordable costs of fixing safety defects that are no fault of their own” are the central concerns of this blog, which by comparison – Reader Alert! – are arcane verging on nerdy. For the record, however, Jenrick’s three key proposals are for:

- a further £3.5bn of government grant to pay for the removal and replacement of dangerous cladding systems on buildings over 18 metres tall;

- for buildings below 18 metres, a long-term “financing solution” of a government loan to the owner, repaid by leaseholders, with a payment cap of £50 per month;

- a new levy for developers, to become applicable when planning permissions are submitted for high-rise developments.

Back, though, to last Monday. Labour’s motion, introduced by Shadow Housing Secretary, Thangam Debbonaire, called for the Government to establish a new, somewhat Starmer-sounding, cladding taskforce that would make buildings with dangerous materials safe and protect leaseholders from the costs. Initial respondent for the Government was, remarkably, the Minister of State for Europe and the Americas, Chris Pincher, not due formally to assume office as Minister of State for Housing for another 12 days. The so-called – and here so appropriately – wind-up was done by Eddie Hughes, Junior Minister for Rough Sleeping and Housing.

As for the not generally publicity-shy Jenrick, he apparently “stayed away entirely”. Which inevitably reinforced the impression, conveyed by his being openly accused of “incompetence” in this matter by his own backbench ‘colleague’, that neither he nor the Government as a whole were any more bothered than they had appeared previously about even being seen to regard this scandal as a major priority.

For the record, Monday’s motion was passed by 263 votes to nil. The Ministers seemed unable to convince anyone that the Government was addressing the issues with anything like the requisite urgency. But Conservative backbenchers, increasing numbers of whom had already been seeking, without noticeable Labour support, to amend the Fire Safety Bill to avoid remediation costs being passed on to leaseholders, chose to abstain, rather than give HM Official Opposition unearned credit.

At which point I must temporarily side-line cladding, while explaining how, almost by chance, I happened upon one of the latest updates in the Institute for Government (IfG)’s occasional series of ‘Explainers’ – on Ministerial Directions (MDs) – a topic about which previously, I confess, I’d bothered myself relatively little.

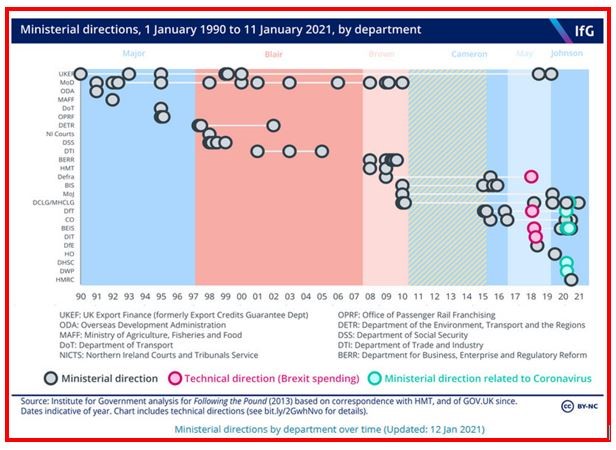

Poor show perhaps, for someone actually endeavouring to teach students about British politics. My rationalisation would have been that, while broadly aware of what MDs were/are and their obvious importance, I sensed that their usage wasn’t that frequent, and that anyway, until “the rules” were changed and GOV.UK was launched in 2011/12, most such directions would indefinitely have remained state secrets.

Unwittingly, I was actually right about the numbers – as shown in one of the IfG’s several excellent graphics: an average of under two a year while I was teaching, compared to 31 in the past three years and 19 in 2020 alone. The explosion, and indeed MDs generally, seemed worth further inquiries.

First, then, what exactly are ‘Ministerial Directions’? In this case, just what it says on the tin: formal directions from Ministers instructing their department to proceed with a spending proposal – and in so doing overriding the principled objection of the most senior civil servant: the Permanent Secretary (PS), who is also the ‘Accounting Officer’, accountable to Parliament for how the department spends its money.

And it’s not just a clash of wills, or opinions. There are specified criteria any spending proposal must meet: that it’s within both the department’s legal powers and agreed spending budget, meets “high standards of conduct”, constitutes value for money, and stands a feasible prospect of being implemented as specified within the intended timetable. If a PS has doubts about a proposal meeting any of these criteria, they must seek explicit direction from the Minister, who thereupon writes a ‘directing’ letter and takes accountability for the decision. Interestingly, that’s often how it seems to work: less a Minister’s wanting to spend overriding the horrified protests of a cautious civil servant than the civil servant seeing or at least agreeing the need to spend but constitutionally requiring the Minister’s say-so.

British politics being conducted in the ‘civilised’/secretive way it generally is, even the traditionally rare occasions on which such clashes come to a head are rarely much publicised, but there are exceptions. Remember Joanna Lumley’s ‘Garden Bridge’ over the Thames – proposed as a largely privately-funded project, but taken up with characteristic enthusiasm by the then Mayor of London and given significant pre-construction funding by the Department for Transport? At which point the Transport Secretary, Patrick McLoughlin, came back wanting more – arguing to the ‘Accounting Officer’ (the PS) and in his Ministerial Statement that there were more than mere transport benefits to be considered and that the Department’s pre-construction commitment should be increased by up to £15 million. It duly was, and of course the Garden Bridge is today the “iconic tourist attraction right in the heart of our capital city” that the Mayor and Minister predicted. Sorry, is it not?

A more specifically local governmenty Ministerial Direction was that the MHCLG should not recover from councils £36 million that, through an error in civil servants’ methodology, they had been overpaid for participating in 100% business rate retention pilots (2017/18). Nice one, Sajid Javid!

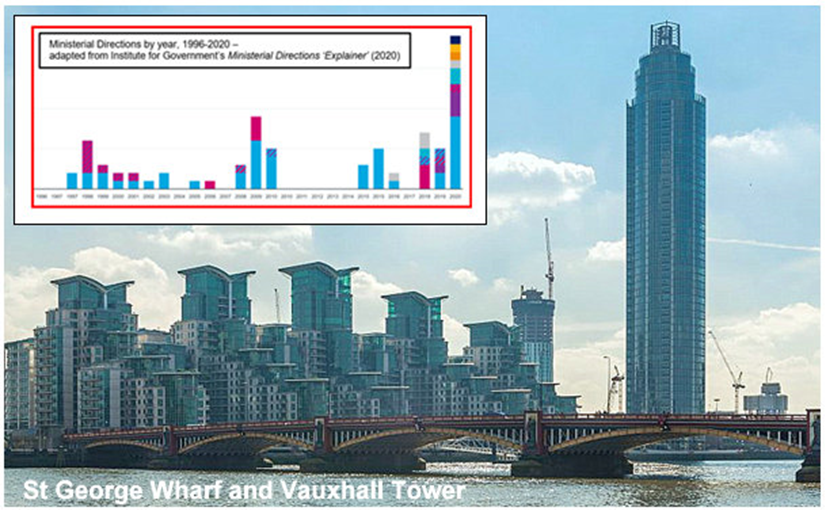

What had particularly caught my interest, though, was that noticeable rise in MDs over the past 2-3 years and the positive explosion under the Johnson Premiership, certainly since the arrival of Covid. In fact, the IfG’s graph reminded me almost immediately of the well-known view of one of the ugliest buildings in London – the Vauxhall Tower overlooking St George Wharf – and, as it happens, just two bridges down-river from the IfG.

There have already been 14 Covid-related Ministerial Directions – worth possibly a blog in their own right – but I’d gone in looking for cladding business, and there it was, in May 2019 – two months pre-Johnson. James Brokenshire, Jenrick’s predecessor as Housing and Communities Secretary, had made clear both his and PM Theresa May’s view that leaseholders should not have to pay – even assisted by the kind of loan scheme announced this week.

It’s worth reading the full exchange of letters between Secretary of State Brokenshire and the Permanent Secretary, but the following extract from Brokenshire’s will convey at least the flavour:

“I understand that, in making these choices, the taxpayer will pick up the vast majority of remedial costs. However, I have considered that against the safety implications for residents and the need for pace. I consider those two factors to be more important.”

The only thing, however, seemingly throughout this whole wretched business, to have happened at any pace was Brokenshire’s own departure, like that of Theresa May herself, to the backbenches. A pity – somehow I don’t feel he would have taken last Monday afternoon off, or that nearly 20 months later there would still have been no Government policy.

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.