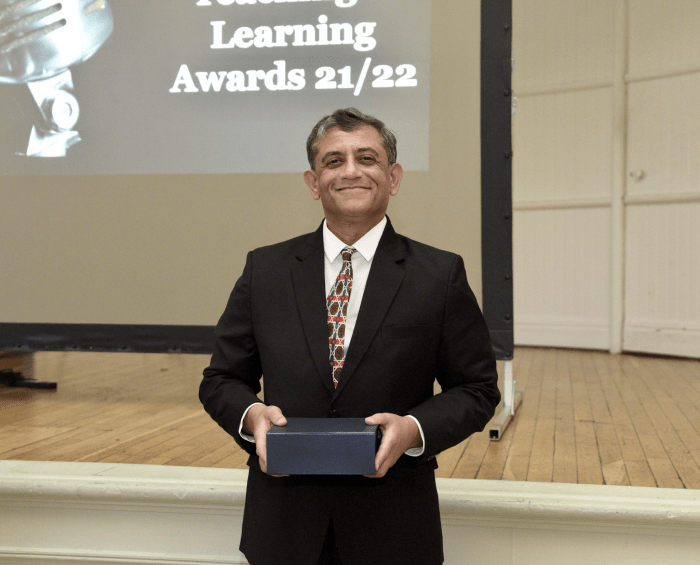

In this blog post, Shailen Popat reflects on how his PhD data collection in primary schools informed his teaching which was recognised by the University of Birmingham.

Shailen Popat

On 6th July 2022, I was honoured to be the recipient of the University of Birmingham Teacher of the Year Award. I am fortunate to have colleagues that are committed to continuous improvement in teaching, and it is heart-warming that they felt that my contribution met the following standard:

‘This award celebrates the achievements of an outstanding colleague who has made a significant and lasting contribution to the provision of education at the University of Birmingham. The award winner will have a passion and drive for education that is recognised and respected by their peers and students. The judges will be looking for evidence of teaching and or supporting learning, and leadership informed by engagement with research, impact on student learning, a commitment to reflection, collaboration and continuing professional development, and extensive influence that makes a notable difference to the provision of teaching and learning at the University of Birmingham.’

Reflecting on the descriptors above such as passion, research-led teaching and impact on students, I realised that many of the innovations that I introduced are sourced from my research in Primary Schools in England. I can recall observing a maths lesson in a rural primary school and it was intriguing for me to see how the teacher organised the students without using ability streaming but sat them in groups according to the speed with which they were grasping a concept where they worked collaboratively and with teacher input. When I was at school we used to be streamed in top, middle, and bottom sets and once you were streamed in this way you only access all of the curriculum if you are in the top set. School teachers are now required to adopt a growth mindset which believes that students of all abilities can achieve learning outcomes through hard work, and this is the culture that we are establishing in INLOGOV courses. We set all students the same demanding seminar tasks each week regardless of prior experience and language proficiency and use peer-led study groups so that students can help each other to understand concepts and practise skills.

One primary school that I visited had implemented a purple learning programme which involved children becoming aware of the importance of coming-out of their comfort zones as learning gains occur when we are challenged. I was impressed how young children were being taught to analyse what their peers were saying and either ‘support’, ‘challenge’ or ‘extend’. In our MSc, we have learnt from that and promoted critical thinking as part of social interactions. This type of learning challenges many students who may have been taught in a school culture of memorising for exams. Research tells us that friction between the students’ learning conceptions, orientations, and strategies, and the demands of the new learning environment creates sufficient challenge to be able to realise their potential. Other research has focused on the study skills employed by students and the potential of training study skills in order to improve student performance. From this perspective, students who master study skills will be able to regulate their learning because they possess the skills to learn in an effective manner and so I designed tasks that would encourage the development of applying concepts such as New Public Management to real-world cases and then requiring students to use those same skills to apply the concept of bureaucracy to another case study.

Chunking is the word that some researchers use to describe the process of breaking large bodies of information into smaller, discrete concepts and skills that can be repeated, refined, and eventually reassembled back into the context of the topic or case study. To be effective in the process of chunking, the teacher must identify the critical elements of the summative assignment that are challenging for the students, and then create a repetition exercise that focuses on the smallest pattern that addresses the identified problem(s). By focusing on the specific problem(s), the educator will be able to give immediate feedback on the specific elements that are problems, and the students will have the opportunity to immediately experience the solution as they produce work in seminars. The repetition should also involve variation in task and contexts as the brain’s natural tendency is to learn from new experiences and then to slowly lessen the response. Reframing techniques are particularly effective because they create a sense of novelty and avoid the sense of boredom that can lead to meaningless repetition.

Shailen Popat works as and Assistant Professor (Education) in Public Policy & Management and is Director of the MSc in Public Management at INLOGOV together with being a part-time DPhil Researcher at the University of Oxford Department of Education.