General Election, opinion polls, YouGov regional poll, regional variations, 1983 General election, Margaret Thatcher, Sadiq Khan

You might think, given the record of opinion polls in the 2015 election campaign, that there’d be slightly fewer of them this time. Dream on! So far this month national voting intention polls have averaged well over one a day. Of the 28, precisely none have shown the Conservatives on less than 44% – that is, over 6% higher than they managed in the 2015 election; and just one – the ‘outlier’ of those published this past weekend – put Labour behind by less than 10%, compared to the 6.6% GB gap last time.

There is an iron law in opinion poll reporting: the more eye-catching and exceptional the finding, the louder it will be reported, and the more likely it is to prove a ‘rogue’ result. Unsurprisingly, therefore, this ‘single-figure lead’ poll prompted instant speculation about whether Corbyn’s Labour could win more votes than it did under Miliband, or even increase its return of 232 MPs, which at least temporarily displaced the McLuskey-prompted ruction about whether just 200 Labour MPs would qualify as a successful campaign.

That would in fact be Labour’s worst result since 1935, worse even than 1983, when under Michael Foot’s leadership it was reduced to 209 MPs. And, while the PM may understandably wince at personal comparisons with Margaret Thatcher, and in her party’s ‘Reddish Tory’ manifesto has certainly distanced herself ideologically, it still seems most likely that it is with that latter election that, as polling day approaches, statistical comparisons will be made – starting in the second part of this blog.

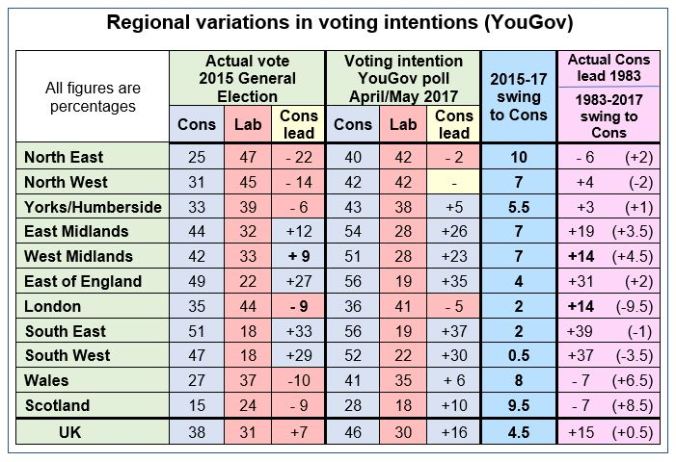

The first part looks at something arguably more interesting – the regional variations in current voting intentions, as collated by YouGov in a total GB sample of over 17,400 respondents, and compared to the actual votes in the 2015 election, summarised in the central sections of the table below.

The ‘headline voting intention’ that would have been reported in YouGov’s late April/early May polls – that is, excluding ‘don’t know’s and ‘won’t say’s and weighted by respondents’ self-described likelihood to vote – would show the Conservatives with a 16% lead over Labour, with the Lib Dems on about 10% and UKIP around 7% and sliding.

The modesty of the Lib Dems’ post-2010 recovery, the recent collapse of UKIP, and the performance of other smaller parties are obviously important and will be decisive in many individual constituencies. But my main concern here is the bigger picture: the variation in the Conservatives’ current lead across the regions, and the extent to which the figures support the claim that Theresa May is increasingly keen to make of her party being truly national in its appeal and support.

We’re used to seeing political maps of the UK, whether of national or local government, from a ‘geographic’ viewpoint: each constituency or council a blob of appropriate colour the relative size of its land area. Shown such a map of the 2015 election results, an innocent visitor would probably conclude that, in England and Wales at least, we’re already there: more or less a one-party state. Even London, where Labour took 45 of the 73 seats, has to be magnified to look more than a red smudge in an ocean of bright blue.

Now, though, following the local elections, Conservatives actually are the largest party in every English county and county unitary authority except Durham, and the regional YouGov polls tell a similar story. The swing of support between the two major parties since May 2015, coupled with the respective performances of UKIP and the Lib Dems, has put us on the brink of becoming, as well as just looking cartographically, a one-party state.

In under two years, one English region, Yorkshire/Humber, has swung from majority Labour to majority Conservative. A second, the North West, has seen a 14% lead completely disappear. And, most strikingly, Wales and Scotland, for decades dominated almost monopolistically by Labour, are both currently showing the Conservatives with a clear two-party voting lead.

In general, and with one big exception, the below-average 2015-17 swings from Labour to Conservative have been in the already strongest Tory areas – the South East, South West, and East of England. And the above-average swings have been in the traditionally strongest Labour areas, where they can make the relatively greater electoral impact: the North East, an early deliverer in the form of an unexpected mayoral victory in Tees Valley; the North West, May’s choice for her launch of the party manifesto; the Midlands, Scotland and Wales.

The massive exception to all this is obviously London, increasingly unmoored in so many respects, it seems, from the rest of the country. Current voting intentions don’t quite match the 44% to 35% split in 2015, and with which Sadiq Khan won the mayoralty last year, but they’re very close.

London’s real political exceptionalism, however, is shown when we start comparing with 1983 and the figures in the final columns of my table. In that election the regional voting figures in London and the West Midlands were close to identical: 44/45% Conservative, 30/31% Labour, 25/27% SDP-Liberal Alliance, and in both cases a (highlighted) 14% Conservative lead.

By 2015 that lead had been reduced to 9% in the West Midlands, but in London had been reversed to one of 9% for Labour. And over the past two years that divergence has accelerated, with the Conservatives 23% ahead in the West Midlands and Labour 5% ahead in London.

The last (bracketed) column in the table is intended to take advantage of the fact that nationally the Conservatives’ current lead in voting intentions is effectively the same as that achieved by Margaret Thatcher’s party in 1983, and to see how the different regions compare and contrast.

Headed massively by London there are four minus signs, but the seven pluses suggest that May’s Conservatives are indeed developing a claim to be a more genuinely nationally supported party than we’ve seen for at least several decades.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.