Chris Game

When I used to teach undergraduate Politics courses, I would try to invite along at least one overseas student when I went to vote – partly for their cultural education, partly to share their impressions.

Their customary first question was: will there be queueing? It would be asked in relation to almost any unfamiliar British activity, but particularly after I happened to have recounted the time a Romanian Presidential Election clashed with Birmingham’s Frankfurt Christmas Craft Market, and police were required to shepherd literally hundreds of remarkably patient Balkan voters round the fringes of the market to the Town Hall, doubling for the occasion as a regional Romanian polling station.

My queueing answer, even for a General Election, was a confident ‘No’. Likewise, to usually the next question: taking photos.

The students would already know about voting in the UK not being compulsory. So the polling station trip’s key ‘learning point’ was identity verification, as they were fully aware that, unlike many of their countries, we don’t have national ID or citizen cards, with or without a photo.

Whereupon I would produce my so-called poll card from the City Council Returning Officer, detailing the election date, my polling station and register number, voting hours, plus “You do not have to take this card with you in order to vote”. They would be underwhelmed by the flimsy, featureless B&W card that almost begs to be junked immediately upon, if not before, being read. So I would tease them by telling them initially that it’s another ‘British tradition’.

Poll cards were first produced for the 1950 General Election, and tradition requires them still to look as if printed by a pre-Xerox mimeograph machine. Compared to our queueing obsession, separate hot and cold water taps, and constant apologising, it usually struck students as among our lesser cultural eccentricities.

But how would I prove my identity? Whereupon I would explain that, although Northern Ireland voters have since 2002 had to produce one of seven possible forms of photographic ID – including, if necessary, a free Electoral Identity Card – as a GB voter, I wouldn’t have to. Indeed, even if I proffered my poll card, the Poll Clerk would still ask my name and address – which I could easily read upside down on the electoral register as it was being marked off.

Meaning, if I wanted to cheat small-time – commit ‘personation’ by having someone illegally cast an extra vote for my preferred candidate – I could easily memorise the names of neighbours who had not yet voted, and select one least likely to in, say, the next hour or so, who could thus be safely impersonated.

Almost invariably, that voting practice summary proved among the most impactful information I imparted to my students. “How British!” was their first reaction, though generally followed by mild but real shock: at our treating so apparently casually this core act of political participation that many of them and their parents’ generation had literally fought – and then queued – for.

All of which is an anecdotal way of introducing my own ambivalence towards the Government’s commitment to extend from 2023 the Northern Ireland practice and require all UK citizens to show photo ID in all the categories of Parliamentary and local elections taking place on May 6th.

So what’s my problem? The Electoral Commission has supported it for years. The policy has been in two winning Conservative manifestos. It will be an Electoral Integrity Bill, which sounds worthy enough. It has been pilot tested – kind of. It worked in Northern Ireland, where ‘personation’ has been largely eliminated.

Besides, since we nowadays show ID for ever more everyday services, it’s irrational not requiring it for something as important as voting. I can almost hear my students agreeing – as indeed do I. My problems are with the Government’s priorities – and the false Northern Ireland analogy.

20 years ago NI had a big, pumpkin-sized electoral problem – public perception of widespread electoral malpractice, including vote-stealing, impersonation, voter intimidation, multiple register entries. GB, thankfully, doesn’t.

The Electoral Commission’s own analysis shows that of 58 million votes cast across the whole UK in 2019, 595 alleged electoral fraud cases were police-investigated – most concerning local elections and campaigning offences. Just four led to convictions, one being for impersonation.

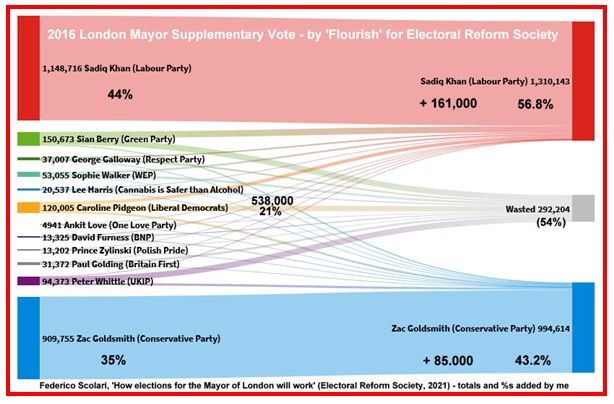

Partly, and sadly, because of widespread political apathy and alienation, GB’s voting malpractice problem is, pinching the Electoral Reform Society’s metaphor, nut-sized – yet to which the Government proposes bringing a clumsy, costly, partisan legislative sledgehammer.

Second, the effectiveness of the NI photo ID reform is almost always judged first by pre-reform turnout rates not having significantly fallen. What significantly rose, though, to today’s seriously disturbing levels, is the incompleteness of the electoral registers on which those turnout percentages are based.

According to the Electoral Commission, just 51% of NI 18-34 year olds were correctly registered in 2019, compared to 94% of over-65s; 88% of ‘outright’ homeowners, but 38% of private renters. Obviously, if you’re not registered, you’re not part of the turnout base. In short, NI today is not an exemplary electoral model for the rest of the UK.

GB’s genuinely big electoral problem, again based on those most recent Electoral Commission data, is that over 9 million, or 17%, of eligible GB voters were either not or incorrectly registered at their current address – particularly, if unsurprisingly, the young, persons of colour, renters, low-income, disabled, and simply those with no fixed address. Many/most of whom – how to put this – would on balance probably not be natural Conservative supporters.

There is an obvious solution: Automatic Voter Registration (AVR) – the direct enrolment of citizens on to the electoral register by public officials; no citizen initiative required. But that’s for another blog.

Meanwhile, if anything should be made compulsory, let’s make it not photo ID, but poll cards: “You SHOULD take this card with you when you go to vote”.

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.