Maximilian Lempriere

At a workshop hosted in early November by INLOGOV, City-REDI and The Public Services Academy at the University of Birmingham practitioners and academics from the world of local government came together to share experiences on the current Combined Authorities and city-region devolution agenda. In the third of a series of posts Max Lempriere, a doctoral researcher studying the formation of combined authorities, reflects on the days major talking points.

Policy makers may dislike ambiguity and flexibility, but devolution to Combined Authorities brings with it a fair degree of both. There are so many questions that will only be answered as the result of experience and so many variations in configuration, governance and circumstances between Combined Authorities that no progress could be made without it. The ‘who’, ‘what’ and ‘when’ is up for negotiation on a localised basis, bringing both benefits and pitfalls. The question is, then, how can we ensure that we maximise the benefits but avoid the pitfalls?

The precise answer to that question is unknown – a pitfall in itself – but leaders in all Combined Authorities need to be willing to look, listen and learn from their own experience and that of others if they are to strike the right balance. Combined Authority leaders need to be willing and able to share and learn from best practice, whether internal or external.

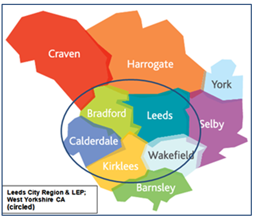

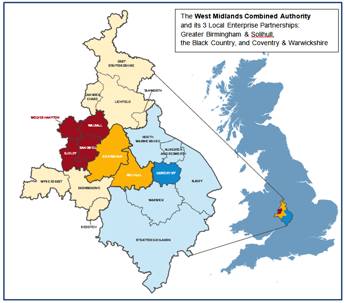

When looking to other Combined Authorities they must remain sensitive to local contexts. Compare those in the West Midlands and Greater Manchester, for example. The latter has historic, clearly defined and coterminous economic and political geographies that lend themselves well to the Combined Authority model, whereas the former has a less clearly defined economic geography and lacks congruence when it comes to political geography. Learning to co-ordinate, collaborate and muddle-through across Combined Authorities is no easy task when there are such differences between them, especially if the implications of actions aren’t immediately clear. Their innovative nature and the variety of contexts in which they are found means that any initial institutional design will only ever be ‘good-enough’.

As a result there will have to be a fair degree of ‘learning by doing’, where the formal and informal rules of the game emerge as decision makers tackle different challenges and obstacles.

However, precise institutional arrangements, devolved powers and funding responsibilities differ from one Combined Authority to another, reflecting as they do local economic and political geographies. The Mayor in Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, for example, will have more powers over housing that their counterpart in the West Midlands and Greater Manchester, in another example, is currently the only Combined Authority to have autonomy over its £6bn share of NHS spending. Understanding common ground for mutual learning will therefore be difficult because it doesn’t just require political and managerial leaders to think in terms of what works but – perhaps more importantly – what doesn’t work when translated into different contexts. The danger, as increasingly seems to be the case, is that Combined Authorities look at what the Greater Manchester Combined Authority is doing well and try emulate that.

This kind of learning doesn’t just need to occur within or between Combined Authorities themselves. Central government must be willing and able to learn from experience on the ground, whilst remaining sensitive to local contexts. Learning from past Combined Authority successes and failures should feed not just into designs for future authorities but should form the basis of continuous, on-going institutional reform – a similar process of ‘muddling through’ and respecting ‘good-enough’ design – to fine-tune existing devolution arrangements to ensure maximum public and added value. Central Government has certainly showed a willingness to look, listen and learn itself in the case of the GMCA – shown in ongoing rounds of devolution deals, the latest of which was announced in the Chancellor’s Autumn Spending Review in November 2015. The challenge is to make sure it does so with other Combined Authorities in a way that respects their successes and failures on their own merits and avoids using the GMCA as a ‘yard-stick’ against which to judge.

An effective way to encourage these kind of local and multi-level learning processes is to incorporate them into the institutional design in the first instance. Formal arrangements to encourage inter and intra-institutional feedback – whether through scrutiny arrangements, joint workshops or regular meetings of officials – can play a crucial role in facilitating feedback and fostering a culture that encourages learning, experimentation and innovation.

But how to overcome the challenges of learning across differing contexts and geographies? Part of the work that INLOGOV, City-REDI and others have been doing is directed towards understanding both the successes and the difficulties experienced by Combined Authorities with a sensitivity to local contexts. Academic insight and the application of theory to practice have potentially crucial roles in cross-border learning of this kind. Situating information-providers and independent assessors within the institutional arrangement will allow decision makers to see more clearly points of mutual comparison.

Practitioners should be willing to learn, be sensitive to what is and isn’t possible in different contexts and embrace ambiguity. Combined Authorities are flexible and incomplete. How we work towards completeness depends on our willingness to learn from mistakes, appreciate best practice and recognise that it may not always be the best idea to copy Manchester.

This series of workshops is being supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, Local Government Association and the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives (SOLACE) and is led by Catherine Staite, Director of INLOGOV and SOLACE’s Research Facilitator for Local Government.

Max Lempriere is a final year PhD researcher at the Institute for Local Government Studies at the University of Birmingham. His research interests include institutional design, local government policy making, devolution, urban planning and sustainable development.