Jason Lowther

With dozens of English councils and hundreds of councillors facing delays to this year’s May elections, opponents claim the move could undermine public trust in democracy. History shows deferral of elections in similar circumstances is rare but not exceptional. There are however far bigger threats to the UK’s democracy.

Media reports today are suggesting that more than a third of eligible English councils have requested to delay their planned May 2026 local elections, potentially requiring around 600 councillors to serve an additional year. These councils state that the Government’s ongoing local government restructure makes it difficult to run the polls effectively at the planned dates, and central government claims holding elections for councils that are soon to be abolished would waste time and money.

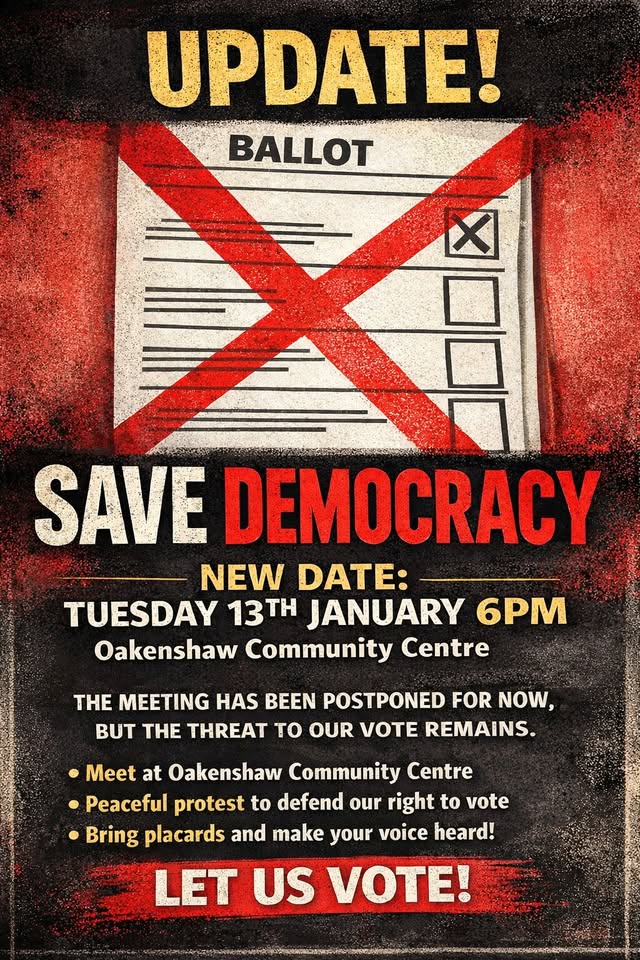

But the delays have sparked criticism, and even led to unrest at this week’s Redditch council meeting. Opponents argue the move weakens democratic accountability. Reform UK leader Nigel Farage denounced the proposal as “monstrous”, claiming that “denying elections is the behaviour of a banana republic” and threatening a judicial review. Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs have also criticised the move. The Electoral Commission’s chief executive said: “As a matter of principle, we do not think that capacity constraints are a legitimate reason for delaying long planned elections. Extending existing mandates risks affecting the legitimacy of local decision making and damaging public confidence.”

Delays to local elections in England have occurred previously. During the Second World War, all local elections were suspended between 1939 and 1944, making this the most extensive postponement in modern history. In peacetime, delays have largely been tied to local government reorganisation, most notably in the 1990s, when Parliament approved major structural reforms that abolished counties such as Avon, Cleveland, and Humberside and created 46 new unitary authorities. These reforms led to altered or cancelled election dates to align with the establishment of new councils and avoid electing councillors to authorities that were about to be dissolved. In 2025, nine councils had their elections delayed by one year to support transitions to new unitary structures.

But even though there are clear precedents for the current electoral postponements, there are other longer-term, more significant and worrying trends which risk seriously undermining our democracy. Academic commentary shows growing concern among constitutional scholars that the UK’s democratic safeguards have weakened in recent years.

Scholars at the UCL Constitution Unit warned in 2022 that the UK faced a real risk of “democratic backsliding,” defined as a gradual erosion of checks and balances, growing executive dominance, attacks on civil liberties and the weakening of political norms that traditionally safeguarded constitutional stability. Their analysis emphasised that democratic decline can occur incrementally through the actions of elected leaders, especially in systems like the UK’s where constitutional rules are flexible and can be rapidly altered.

Further alarm was raised by Professor Alison Young at the University of Cambridge, who described the UK as standing on a “constitutional cliff‑edge.” In her 2023 book, she argued that a series of constitutional changes and executive‑centric reforms have strengthened government power while weakening the political and legal checks that previously constrained it. Young warned that without reforms to reinforce accountability, transparency, and oversight, the UK risks drifting towards “unchecked power,” eroding the democratic norms that underpin good governance.

Last year, Dr Sean Kippin of the University of Stirling argued that recent Conservative governments engaged in “democratic backsliding” by deploying what he calls an “illiberal playbook,” using both lawful and legally dubious tools to weaken institutional checks, restrict protest rights, and compromise the independence of the Electoral Commission. His research concludes that “between 2016 and 2024, the Conservatives used power to diminish, weaken, and compromise Britain’s already imperfect democracy”.

There have been some positive moves by the ‘new’ Labour government to improve the functioning of our democratic system, such as the widening of voter ID criteria and promises to lower the voting age to16. However, overall there hasn’t yet been commitment to fundamental reforms to address the issues identified in the above reports, such as the impact of donations on political impartiality, and there have been some worrying developments, for example around civil liberties and the right to protest.

A year’s deferral of elections to a disappearing council doesn’t fundamentally undermine our democracy, but failing to address the longer term and serious issues of democratic backsliding could prepare the way for those who will.

Dr Jason Lowther is director of INLOGOV (the Institute of Local Government Studies) at the University of Birmingham.

References

Kippin, S., 2025. Democratic backsliding and public administration: the experience of the UK. Policy Studies, pp.1-20.

Russell, M., Renwick, A. and James, L., 2022. What is democratic backsliding, and is the UK at risk. The Constitutional Unit Briefing.

Young, A.L., 2023. Unchecked power?: How recent constitutional reforms are threatening UK democracy. Policy Press.

Picture credit: https://www.facebook.com/events/898249983102646/