Anthony Mason gives an initial assessment of the white paper on housing and planning in England

First impressions are not always very reliable. When Sajid Javid replaced Greg Clark as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government following the post-vote governmental putsch last year (sorry, change of Prime Minister following the referendum), local government figures were very wary. Clark had, and still has, a reputation for understanding local government and can connect the local to the national in discussions around the cabinet table in a way that few of his colleagues are able to. Javid, however, was an unknown quantity – said to feel that the DCLG role was a demotion and giving every indication that he was unexcited by the move.

Yet, for those of us specifically interested in housing policy, Clark – alongside his spiky and confrontational housing minister, Brandon Lewis, presided over some rotten housing policies, as I suggested in this place last year. Indeed, the Housing and Planning Act 2016 will, I suspect, go down in legislative history as the Dangerous Dogs Act of housing policy in England. Gratifyingly, a number of the craziest measures enabled by that Act have proved so difficult to implement that the “new” government has simply shunted them into a siding and (we hope) left them there to rot.

And now comes the first comprehensive white paper on housing policy in England for almost a generation. Bearing the less than poetic title-as-ambition of Fixing our broken housing market. Javid and his refreshingly rounded housing minister Gavin Barwell, set out in 104 pages and many supporting papers their ambitions to do just that. To their great credit, Javid and Barwell have spent many weeks on careful consultation with local government, sector interests, and Number 10 before getting this far; delaying the publication of the white paper somewhat while doing so. They have even persuaded the PM to pen a lengthy introduction to the paper – presumably in the hope of corralling rural Conservative NIMBYs into line.

The white paper sets out many proposals and poses 38 carefully framed policy questions for response (by 2nd May 2017, if you’d like to contribute). But in quick summary, it:

- Acknowledges that England needs around 250,000 new homes each year going forward. This was expressed as “between 225,000 and 275,000 homes” – and is up from the oft-quoted 200,000 previously accepted (but never consistently realised)

- Proposes that each local authority will have to draw up and regularly review an “honest assessment” of local housing need – methodology to follow.

- Says that developers could be forced to build within two years of planning consent, or see that consent lapse. At the moment, permission usually lapses after three years. The paper also proposes new compulsory purchase powers for councils where sites lie undeveloped – details to follow.

- Suggests an expanded and more flexible affordable homes programme, for housing associations and local authorities, with £7.1bn of (already announced) funding. It drops the “old” government’s fixation with starter homes in favour of a more balanced approach.

- Encourages building rates at higher density – including of higher buildings – to make best use of land (and to avoid having to give a view on releasing green belt).

- Dodges the question of future housing association and council rent levels after George Osborne’s compulsory rent reductions “We will provide clarity over future rent levels. In return, we expect them to build significantly more affordable homes over the current parliament.” Is what ministers promise.

- Says that smaller building firms will be given assistance to expand, including support for off-site construction (where components are fabricated off-site and factory-assembled). It also encourages “build to let” where private companies build large-volume rental flats for tenants.

- Continues a focus on leaseholds, proposing what it calls “an end to leasehold abuse” where home buyers are locked into leases with spiralling ground rents.

Most of us acknowledge the general need for new homes while protesting loudly if those homes are to be built near to us – and for years, housing policy in England has tried not to upset voters and yet deliver new homes. And the white paper has had to throw titbits in all directions to keep sector interests at bay. Local authorities are both excoriated for planning failures and mildly encouraged to build new homes. Those who worship at the altar of home ownership will be pleased that there is a threat to close a loophole that has allowed councils building homes through wholly-owned companies to avoid the right to buy. Those who see renting as the most realistic way forward will be pleased that much of the white paper acknowledges this reality and makes gentle proposals for longer tenancies. Big developers are both criticised for not building out sites as well as encouraged by some anti-planner language.

But ministers have failed to resolve some longstanding conundrums – and a couple of new ones – in their paper:

- Successive governments have tried to combine bottom-up and top-down policies on housing which appear to conflict in their efforts to encourage and coerce. For example, communities and parishes have been given more control over developments and yet principal councils are still required to provide new homes. Housing associations should develop more and yet have no control over the rents they can charge for these new homes.

- Government has long had an intellectual tendency to support developers over planners – even though planning consents have been running ahead of homes built for some time. This white paper at last begins to recognise that not all is well, with our developers while avoiding the obvious response: councils’ potential contribution to building at scale.

- There is a cherished belief that brownfield sites can provide the majority of our new homes, but these sites no longer match need. Not surprisingly, they are disproportionately in cities, but not all housing need is city-based. The white paper avoids the question of building on the green belt, even though, in our own city, we’ve faced a highly charged debate about this topic.

- A further concern is around labour and skills. We’ve long worried that not enough UK youngsters express any desire to work in the building industry. This is now compounded by fears of the actual or apparent impact of Brexit on the non-UK workforce.

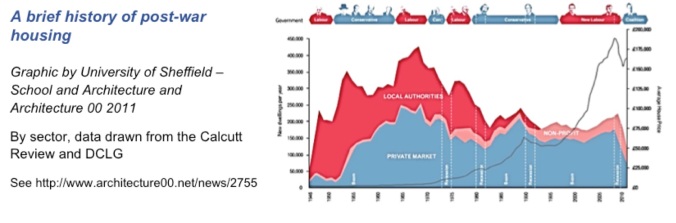

The fundamental question that the paper avoids is whether any combination of our present arrangements for building can ever deliver the amount of housing we need; as the answer to that question may be too hot to handle. It’s old evidence now, but the Calcutt review of the housebuilding industry commissioned a decade ago set out a straightforward graphic showing who has built what in the UK in the years since the Second World War (see figure one on page 10).

This evidence was summarised in a beautifully simple graphic (above) by the University of Sheffield School of Architecture. It evidences that the three decade long gap in our housing provision is simply because we’ve stopped building council houses. The answer to the fundamental question would seem to be to let councils (and housing associations) build again at some scale in order to supplement the relatively fixed-but-declining contribution of private developers.

This evidence was summarised in a beautifully simple graphic (above) by the University of Sheffield School of Architecture. It evidences that the three decade long gap in our housing provision is simply because we’ve stopped building council houses. The answer to the fundamental question would seem to be to let councils (and housing associations) build again at some scale in order to supplement the relatively fixed-but-declining contribution of private developers.

The title to this post is a common misquotation of the Hippocratic Oath. It suggests that a first duty for medics is not to do harm “Primum non nocere” – and the new white paper seems to pass that test, at least. If a second duty is “then to do good” – then I’m not yet convinced that the paper will achieve that in any significant way.

Anthony Mason is an Associate at INLOGOV and works mostly on local government systems and organisation and on improving public sector partnerships. His early career was in local government followed by more than 20 years in PwC’s public sector consultancy team.