Chris Game

‘Five Days in May’: the time it took in 1940 for Churchill to manoeuvre the War Cabinet into a five-year World War, in 2010 to form Britain’s first post-war peacetime coalition – and in 2014 for Tower Hamlets LBC to announce its local election results. OK, I’ve exaggerated – it was actually 119 hours after the polls closed, so only 4.96 days, but still not good, even discounting the malpractice allegations.

However, as in all competitive contests nowadays, there are positives to be quarried. First, as a mayoral authority, Tower Hamlets’ key result, announced a mere 28 hours after the polls closed, was the re-election of Mayor Lutfur Rahman. And here’s the second positive: in TH that key result is effectively the outcome. Once you know the mayor and his party (Tower Hamlets First), you know the politics of the administration – just as with a majority party in a non-mayoral council.

My first moan, therefore, in the grumbly part of this blog, is less about TH’s dilatoriness than about that of too many of the 30-odd councils whose results were reported in the media as NOC – No Overall Control, and where, from the parties’ seat totals, we couldn’t deduce or guess the eventual outcome.

The BBC’s Vote 2014 table is an example of what happens nationally. It’s authoritative up to a point, listing the parties’ seat numbers and net gains or losses. But then, right at the bottom, after all the parties, the Independents, and even the council-less, member-less Socialists, we have No Overall Control 32 (8 net gains). And, of course, it’s still there, six weeks later and possibly in perpetuity – the media’s limited interest in local elections having completely evaporated after the horse race bit.

However it’s used, NOC is an unsatisfactory term – conjuring up, for the highly-strung, alarming images of packs of out-of-control, newly elected councillors roaming the streets wreaking who knows what havoc, for apparently the next four years. It’s more seriously misleading too, as noted recently by Democratic Audit (DA), the blog run by the LSE’s Public Policy Group. NOC gives no hint that a perfectly conventional governing administration will be formed, probably within days, but signifies only that no single party has a majority of council seats.

Moreover, in excluding from the lists of councils gained and lost those in which a party has the largest, but minority, share of councillors, it distorts the parties’ true performances – this year at the expense of the Conservatives and Lib Dems. Their councils ‘won’ would increase respectively by a third (41 to 58) and a half (6 to 9), if their NOC councils were added, compared to Labour’s barely 10% increase (82 to 91).

But Democratic Audit’s greater concerns are with the bigger democratic picture, with the lazy NOC label as but one of a whole catalogue of ways in which all of us – and particularly the civically disengaged young people politicians claim to be so concerned about – are kept lamentably under-informed about all aspects of local elections.

This is the crucial point, and it stems, like so much else, from the huge difference in the public and media attention paid to national and local government. Given the pre-election scaremongering in 2010 about the dire consequences of a hung parliament – from a run on the pound to more or less the end of western civilisation – there was immense pressure on the leading players to come up with something that could be sold to us as at least short- and optimistically medium-term ‘Control’. So we were informed of this outcome, the Coalition Agreement, almost literally within an hour of its settlement.

In local government, all too often, we’re never officially told of the outcome – not even the residents and electors of the NOC councils themselves – as was highlighted this year not just by DA, but also by Local Government Chronicle editor, Nick Golding. During its local elections coverage, LGC monitored councils’ and local newspaper websites – with not just disparate and depressing, but often downright ‘incomprehensible’, findings. It was disappointing, suggested Golding, if “perhaps unsurprising … that some newspapers buried their coverage or failed to work out how individual results could change the political complexion of an authority”.

“What was incomprehensible was the failure of many authorities to highlight their polls. Many council homepages made no reference to the elections and hid elections news in obscure corners; many seemed incapable of promptly posting the results for each ward or revealing how their chamber’s political make-up was changing as a result. Others seemed to think it was the job of someone else to tweet results.”

Of all the defining characteristics of local authorities, the one that most differentiates them from the other local bodies with whom they increasingly work, and that gives them their unique legitimacy, authority and accountability, is surely their direct election. As Golding exhorts:

“Local elections are therefore a big deal. Councils should do everything in their power both to generate excitement about the poll and ensure people know their representatives’ identity. Such tasks are not gimmicks – they are essential components of serving as place leaders. If councils cannot show an interest in their own elections, it is hard to see why their residents should.”

‘Everything in their power’! Yes, indeed, but let’s at least start by eliminating the ‘incomprehensible’. What Golding and I find truly incomprehensible is why scores of councils should CHOOSE NOT to announce – on the home page of their websites and at the earliest opportunity – the overall result of their local elections; PLUS how, within a single click, voters and residents can find their own ward results – vote totals and percentages, turnouts, and whether gained or retained – and the equivalent for the whole council.

Ultimately, though, even more important than results are outcomes. If one party has an overall majority of seats and will in all probability form a one-party administration, this too should be indicated – with, if felt necessary, the date of Annual Meeting at which this will be formally confirmed. And, for the NOC councils considered here, there should be some brief explanation of the implications of no one party having a majority, and again an indication of when the prevailing inconclusiveness will be resolved.

Right, grumbling mainly over; time, overdue, for a change of mode – from moan to puff. As ever with local government, some authorities already do these things exemplarily – one example cited in the INLOGOV Briefing Paper for which this blog is a promotional puff, being West Lancashire BC, whose only two parties exited the elections with 27 seats each and facing a three-week hiatus until the council’s AGM. Prominently on the council’s website, within days, was a model holding statement of the “next step for the Borough’s political management structure”, explaining that the incumbent Conservative Mayor would have the casting vote at the Annual Meeting, and that therefore the new Mayor would probably be another Conservative, who in turn would have a casting vote in the determination of the Council Leader of a likely Conservative minority administration.

It was informative without appearing, given West Lancashire’s political culture, to compromise officers’ political neutrality; also predictively absolutely spot-on. It was, though, at the ‘helpful’ end of a really rather a long scale – at the other end of which were the councils who took several days even to post their election results, and those who still treat councillors’ party identifications as if they are Official Secrets, refusing to divulge even those of executive members until you go to their individual contact details.

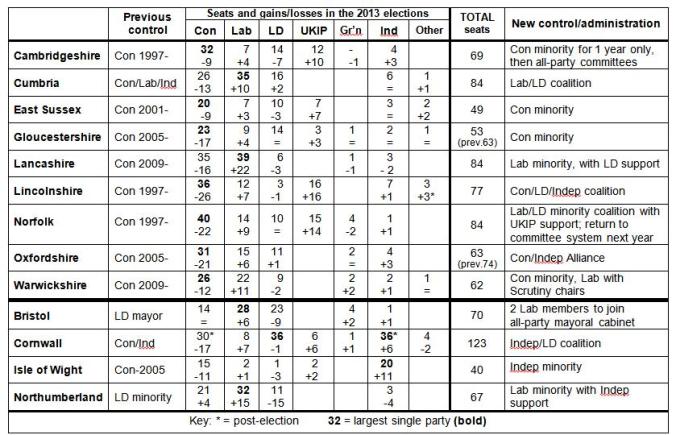

Anyway, the thing is that such councils do exist and, to adapt the much parodied advert, I’ve crawled through their various hoops so that you don’t have to – if indeed it ever occurred to you to do so. Structured around the accompanying table, it provides in one place a record of the eventual outcomes of the elections in this year’s 30 NOC or hung councils (32 if you add two mayoral authorities), and of how, particularly in some of the more noteworthy cases, these outcomes emerged.

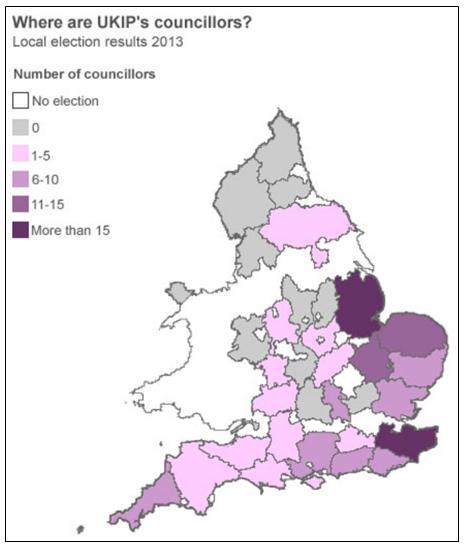

Let me conclude, then, with one summary and one taster paragraph. Single-party minorities are undoubtedly the current NOC administration of choice, outnumbering 20 (13 Conservative, 6 Labour, 1 Lib Dem) to 10 two- or multi-party coalitions, the cause of the latter possibly having suffered from events at (the Palace of) Westminster. The coalitions, though, are striking for their almost Cleopatran infinite variety. The Lib Dems are involved in 8: 4 with Labour, 3 with Conservatives, and in Weymouth & Portland’s all-party administration with both. The Conservatives are involved in 6, Labour in 5, Independents, themselves of impressive variety, in 7, Greens in 1, and, depending on whom in Basildon you believe, UKIP in 1.

If there’s a positive by-product of having to ferret out from councils’ websites information that should be readily accessible, it must be the serendipity factor: you do occasionally come across quirky or gossipy stuff you didn’t previously know. Like, in alphabetical order, the new administration committed to getting on first-name terms with officers and staff (Brentwood); the political group whose acquisition of just one additional councillor necessitated a name change (Colchester); the city with probably the least love lost between its MP and council leader – of the same party (Peterborough); the council where UKIP took power from Labour and then gave it back again (Thurrock); the council whose first and only UKIP member is one Francis Drake (Weymouth & Portland); and finally, the council (some of) whose members seem least inhibited about confirming the public’s worst suspicions of politicians’ motives (Worcester).

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.