Howard Elcock

Do we know what local government is for? Is it just a device for providing services to people at the behest of the central government, or does it provide local citizens with a means of making policy choices about what they want their councils to do? In the 19th century John Stuart Mill and Charles Toulmin Smith debated this issue, with Mill taking a centralist view that local government is an agent acting for the centre and a training ground for would-be Parliamentarians, while Toulmin Smith argued that local authorities are and must be elected bodies chosen by local people to make local choices on their behalf(Chandler, 2007), a view echoed by Professor John Stewart (1986).

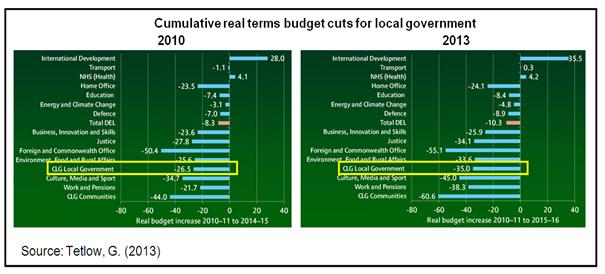

Today local authorities are much too dependent on central government to be able to make major local choices. In 1976 the Layfield Committee said that if central government provided more than 40 per cent of local authority funding, this would make local councils excessively dependent on the centre. Today that proportion is between 70 and 80 per cent as a result of rate capping, the bitter legacy of the Poll Tax and incremental funding decisions to support local services with central grants. Beyond all this, local authorities are dependent on Westminster and Whitehall for their very existence, as has been demonstrated by repeated and largely enforced reorganisations imposed on local government by Parliament since 1972.

The role of local government can be discussed in terms of its five purposes. The first is to represent the different political balances in different parts of the country. In England this has become an acute issue as a result of the recent Scottish independence referendum because devolution for England is being discussed partly in terms of proposals such as “English votes for English laws” and the creation of an English Parliament that treat the country as a unit and ignore the major differences in the economic interests and political balance between the North and the South-East, which ought to be reflected in any proposals for constitutionals change. Enhancing the autonomy of local authorities would be one way of achieving this.

Secondly, councillors are the only elected representatives apart from Members of Parliament who can hold public servants to account on behalf of their electors. Thirdly, local authorities can adopt varied methods of providing local services which may provide models for other public authorities to copy. Fourthly, local authorities provide responsive and accessible services that can be sensitive to local needs and wishes – something the central government with its responsibility for 60 million citizens cannot hope to achieve. Lastly, local control of certain activities has long been regarded as a defence against tyranny. For example, the local control of police forces ensures that the central government cannot enforce its policies on the control of public order without persuading local police forces to comply with its demands. Again, the dispersed ownership of computer systems may provide a protection against an all-knowing and all controlling central state.

However, all these purposes are in danger of being diluted or even lost as a result of excessive central control. The diminished powers of local authorities mean that they are not able fully to represent the views and interests of their local citizens. Secondly, their ability to hold public servants to account has been weakened by the creation of increasing numbers of non-departmental public bodies (“Quangos”) with no local and tenuous national accountability to elected representatives, as well as by the enforced privatisation of local services including care homes. Thirdly, local initiatives are stifled both by financial restrictions and excessive regulation, especially through target setting by Whitehall departments. Fourthly local government has been made less local by the creation of smaller numbers of increasingly large units of local government, especially unitary authorities that cannot easily identify and respond to the concerns of local communities within their wide areas. Lastly, central control over public services has been increased by financial constraint, reorganisation and over-regulation, thus increasing central control even over services such as policing where local control is an important bulwark of democracy and accountability, which has not been significantly reversed by the 2011 Localism Act (Jones and Stewart, 2012).

It will take bold Ministers and a collective commitment by the central government to reverse these trends, particularly because the Treasury will be staunchly resistant to an effective programme of renewed devolution of powers and functions to local authorities. Such a programme would have to include an end to council tax capping, the introduction of new sources of local revenue such as a local income tax together with the reduction of central government grants towards the 40 per cent limit recommended by the Layfield Committee. This must be accompanied by renewed creation of truly local democracy by strengthening the powers of parish and town councils and securing their creation where they do not now exist. The dead hand of central regulation and target setting must also be relaxed. Lastly, the rights, duties and powers of local government must be guaranteed under a written Constitutional settlement. I fear that this is too big an agenda for any of our political parties to cope with.

References

Chandler, JA, (2007) Understanding local government, Manchester, Manchester University Press

Jones, G and JD Stewart (2012): “Local government: the past, the present and the future”. Public Policy m& Administration, volume 27, no. 4, pp. 346-367

Layfield Committee (1976): Local Government Finance, Cmnd 6453, London, HMSO

Stewart, JD,(1986): The New Management of Local Government, London, G Allen & Unwin

Howard Elcock is Professor (emeritus) at Northumbria University. He is author of Administrative Justice (1969), Portrait of a Decision: the Council of Four and the Treaty of Versailles (1972), Local Government (three editions 1984–1994) and Political Leadership (2001). His current research includes political leadership and elected mayors; local democracy; and the ethics of government.