Chris Game

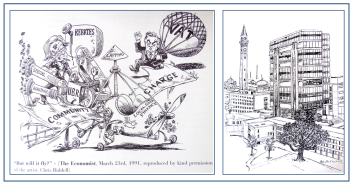

The topical, and certainly most agreeable, purpose of this blog is to applaud the appointment of illustrator, cartoonist and writer, Chris Riddell, as the ninth Children’s Laureate. The enviably talented Riddell has been The Observer’s political cartoonist for 20 years and is also a writer and multi-award-winning illustrator of children’s books. But before any of that fame and fortune, he generously provided easily the most eye-catching half-page in an INLOGOV undergraduate degree recruitment brochure. His still spiky cartoon captures those history-changing few days in March 1991 when the Major Government dumped Mrs Thatcher’s community charge/poll tax, slashed existing bills by raising VAT from 15 to 17½%, announced what would become the replacement council tax, and saved the 1992 General Election.

For younger, or possibly overseas, readers, the distraught pilot of the community charge flying machine with its flying pig emblem (and looking just a little like the late Michael Foot) is Michael (now Lord) Heseltine, then in his second stretch as Environment Secretary, and the VAT balloon man is the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Norman (now Lord) Lamont.

The accompanying sketch has no connection whatever, except that it’s the only art work – as opposed to artwork – I ever actually commissioned for a recruitment brochure, by Rose (Rosetta) Checkley, a then member of our secretarial staff. It shows the Joseph Chamberlain Clock Tower (‘Old Joe’), the unrefurbished Muirhead Tower, where INLOGOV is today, and in the foreground the JG Smith Building, where we were then.

It would be really good now to segue into a blog on, say, the kinds of things Chris Riddell will be promoting or fighting, like school libraries and public library cuts. But I can’t, so instead it’s a Python-style Now-for-Something- Completely-Different moment.

Leaders of England’s 150 largest councils should be receiving about now a letter from Kevin Davis, Conservative leader of the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames council, urging them to follow Kingston’s lead in introducing a system of councillor recall.

It’s hardly a new idea. We hear it almost whenever a councillor is revealed to have ‘forgotten’ to declare a significant pecuniary interest, confided their tasteless personal opinions to Twitter and the world, or simply failed persistently to attend council meetings.

It has slowly come to the boil in Kingston, though, after a Liberal Democrat councillor was dismissed from his party group over allegations of falsely claiming more than £3,600 in council tax benefit. He was eventually convicted, but in the long meantime he continued sitting as a councillor and claiming his £7,500 annual allowance.

Moreover, if re-elected, he could have continued doing so even after his conviction, since the offences carried a maximum tariff of less than a three-month prison sentence. Understandably, many constituents were angry that, under existing rules, there was nothing they could do. In future, though, there may be.

Kingston council will vote next month on innovative proposals to give voters the power to sack their local Councillor. Several suggested scenarios could trigger a petition calling for a by-election. They include a Councillor’s attendance at meetings over a municipal year falling below 20%, conviction of a crime resulting in any prison sentence, and moving their main residence outside the Royal Borough.

If any of these criteria are met, the council’s monitoring officer would decide whether a petition should be launched on the council website calling for the Councillor’s resignation. Ward electors would have three months to sign the petition, and, if more than a third do so, the Councillor would be expected to resign, triggering a by-election.

The ‘expected to resign’ formula obviously reflects the voluntary nature of the procedure at this stage, even if adopted. But Councillor Davis hopes it will be taken up across local government – hence the letter to council leaders – and eventually embodied in legislation.

My guess, though, is that Ministers, however fondly they may currently feel towards the electorate, are likely to be pretty suspicious. For this ‘let’s trust the voters’ business is just the kind of contagious democratic populism they felt had to be stamped on in the last parliament in relation to MPs’ recall.

Some Members – like, as it happens, Kingston’s two MPs, Zac Goldsmith and James Berry – argued for a genuinely voter-initiated recall process. Instead, we had the Coalition’s half-hearted and unconvincing concession that voters will only get even a chance to remove their MP if s/he is actually jailed or fellow MPs give their permission first.

It was a promising opportunity cynically wasted, so it’s encouraging that the recall principle is being kept in the public eye by this Kingston initiative. However, if we’re looking at local government, while being able to instigate the recall of councillors is undoubtedly important, it’s surely even more vital to have a robust procedure in place to remove, if necessary, those with serious executive power.

At present, that means particularly the metro-mayors that the Cities & Local Government Devolution Bill sets as the accountability price for a combined city regional authority to be trusted with Chancellor George Osborne’s “full suite of devolved powers” over transport, policing, economic development, health and social care.

Obviously, elected executive mayors don’t constitute the only, or even necessarily the best, model of city or county regional leadership and accountability. It reeks, particularly ironically for a devolution policy, of one-size-fits-all, and it’s almost nationally embarrassing that this and previous governments haven’t cared enough to compare and consider models deployed effectively in other European cities: leaders’ boards, elected and unelected assemblies, standing conferences of key stakeholders.

But sadly, that’s not how UK governments work, of any political colour. They use parliamentary majorities backed by a quarter of the registered electorate to enact dogma-driven rather than evidence-based policy, and this government’s devolution dogma is metro mayors, at least for city regions.

In a governmental system as centralised as Britain’s, therefore, if elected mayors are the government’s condition for ‘far-reaching devolution’, and it was in the party’s election manifesto – as metro-mayors were – you work with and try to make the best of it, which in this case should mean including in the legislation an electoral recall procedure.

That’s what Germany did in the early 1990s. After decades of different local government systems in each of the four Allied occupational zones, and following the country’s reunification, there was throughout the Länder what one commentator described as a “bushfire-like spread of the direct election of mayors”, driven by concerns about performance and democratic deficits.

Bushfires tend not to consult much before they spread, and neither did the Länder governments. They legislated and imposed. BUT, as a quid pro quo, all the newly mayoral Länder also legislated procedures whereby a sitting mayor could be removed from office through a local referendum – a direct democratic instrument to hold the mayor politically accountable. It was obviously inspired by the recall mechanism used widely in the US, though, with all mayoral municipalities having elected councils, in some Länder the actual referendum is triggered by, say, a two-thirds majority vote of councillors, rather than by a citizen petition.

In the week when Tower Hamlets voters elected a mayor to replace one they themselves played no direct part in removing, it is worth emphasising the importance of both the existence and accessibility of these recall mechanisms in easing German citizens’ early acceptance of what for most was an alien institution.

They had their teething problems – in Brandenburg, for instance, whose voters were so taken by their new democratic power that mayoral recall became for a time a new popular sport: ‘Burgermeisterkegeln’ or playing bowling with the mayors. Generally, though, the prominence given to recall proved both good politics and good government – as surely it would be here.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.