The last Valentines have been sent, the last Chinese New Year firecrackers ignited, the last pantomime cast dispersed – even from Bradford’s glorious Alhambra, where Robin Hood was outlawing away well into February. In short, Winterval is indubitably over, and here in Birmingham, just possibly, over for ever. Not, please note, over for good – not as far as I’m concerned, anyway. PR disaster though it became, I liked Winterval.

I liked it back in 1997, when it was launched by the then Labour City Council, for its brief two-year lifespan. It seemed an imaginative, inclusive and surely innocuous idea. And, 13 years later, it still does – notwithstanding that, towards the end of every one of those years, rent-a-quote Tory politicians, publicity-seeking church leaders, and our agenda-driven, fact-careless media have used Winterval myths to mock the alleged PCGM (Political Correctness Gone Mad) of Birmingham Council in particular and local government in general. For that’s what Winterval became: not just an innocent idea pointlessly destroyed, but a long-running urban myth.

Like most effective myths, Winterval was not totally invented. Rather, it started as an unremarkable, and largely unremarked, initiative, which subsequently gained folkloric status by continual exaggerated and distorted retelling. There never was any proposed ban by ‘barmy Brussels bureaucrats’ of straight, or any other shape of, bananas; but yes, there was a European Commission regulation categorising bananas partly by their curvature.

Similarly, Birmingham City Council never proposed renaming, demeaning, let alone abolishing or banning Christmas (as if it could). But yes, it did for two years use ‘Winterval’ – a conjunction of ‘Winter’ and ‘festival’ – as an umbrella marketing strategy to promote, collectively as well as individually, the numerous religious, secular and commercial events taking place over the three-month period from, in 1998/99, Halowe’en, Guy Fawkes Night and Diwali, through the switching-on of the Christmas lights, the Frankfurt Christmas market, Advent, nativity plays and carol concerts, Hannukah, Ramadan and Eid, Christmas, Boxing Day, and New Year’s Eve, to the January sales and the Chinese/Lunar New Year, which in 1999 fell on 16th February.

It’s how, and how extensively, this actuality was distorted into the destructive and apparently unstoppable Winterval myth – “Birmingham rebrands Christmas” – that provides one reason for revisiting it here: not because it’s exceptional, but precisely because it isn’t. Local government suffers at least as much from this alarmist myth regurgitation as the EU and the Health and Safety Executive. Both these bodies have tried everything to quash unfounded, and potentially scary, myths – from systematically documenting their falsity to producing website lists of the most bizarre – but still they’re regularly trotted out by lazy journalists or motivated malevolents.

Local government has faced the very same problems over the years – from Baa Baa Green Sheep and manhole-renaming allegations in the Loony Left 1980s to David Cameron’s imagined conker bans in school playgrounds. The one unusual feature of Winterval is that, thanks largely to the diligence of media blogger and tweeter, Kevin Arscott, we have a comprehensive chapter-and-verse account of who the myth-perpetrators were, from which much of the following summary is taken.

Before examining the myth, though, here are a few Winterval facts:

- Birmingham City Council (BCC) did not coin the term, but it was the first body to use it on a large scale. It was not devised to avoid offending, or following pressure from, Muslims or any other faith or non-faith groups, but, as noted above, as a marketing strategy, by the Council’s Head of Events, Mike Chubb.

- The first Winterval was over Christmas 1997/98. It was widely welcomed, enjoyed, judged successful, and not one critical media story was recorded.

- The first media attack on what proved the final Winterval – “a way of not talking about Christmas” and thereby offending “people of other faiths” – came in November 1998 from the then Bishop of Birmingham, Mark Santer, in his diocesan Christmas message. The Bishop was quoted in the Birmingham Sunday Mercury as accusing BCC of censoring Christianity and “replacing Christmas”, which quickly went the 1998 equivalent of viral, becoming “cancelling” in The Sun and “renaming” elsewhere across a slaveringly receptive national media, ever on the look-out for cases of town hall PCGM. By the turn of the year, despite the Council’s repeated rebuttals, it had received the Irish Times’ ‘Clown of the Year award’ as “the city council that abolished Christmas”.

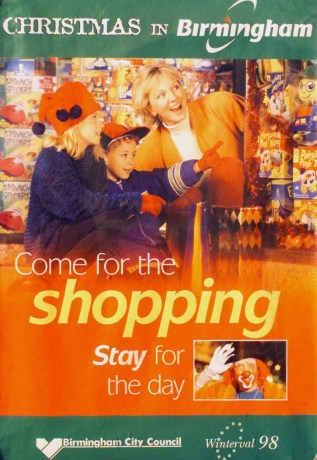

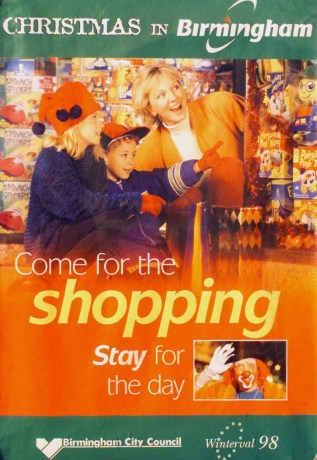

- The extent of the “replacement” or whatever can be judged from the Council’s official poster. A blatant appeal to commercialism and materialism – certainly, and no doubt irksome to the Bishop. But surely even he might have conceded that sticking CHRISTMAS in a three-word headline and your alleged replacement in the bottom right-hand corner is an odd way of ‘not talking about’ something and announcing its cancellation.

- Poster

It was, of course, not Christmas that was cancelled after 1998, but Winterval – although you’d never have guessed it. For the further into history Winterval itself receded, the greater the frequency with which the myth was recycled and embellished. The dozen or so newspaper references a year from 1998 to 2004 have increased since 2005 to over 30. In the last two seasons alone, we have had, in addition to numerous ‘professional’ journalists, Jonathan Aitken, the Archbishop of York, Pope Benedict (“Pope’s Battle to save Christmas” from the depravities of Birmingham councillors – Daily Mail, 18 September, 2010), Lord (George) Carey, the Christian Institute, Frederick Forsyth, Eric Pickles and Ann Widdecombe: scrupulous fact-checkers all.

We have also had some additional twists, to keep the ball rolling. In 2004 The Sun started a ‘Don’t Sack Santa’ campaign, to restore Santa Claus to the Bullring shopping centre from which he’d never been excluded. Then the Royal Mail was dragged in, accused of ‘banning religion’ by omitting depictions of the Bible story from its Christmas stamps – by journalists evidently unaware of its policy of annually alternating between religious and non-religious themes.

So who or what has been chiefly responsible for creating and so effectively sustaining the Winterval myth? A combination of a carelessly ignorant bishop, sloppy journalism, and undue editorial deference to the pronouncements of church leaders, or is there something more sinister? Kevin Arscott, documenter of these events, thinks there is. He traces how Bishop Santer’s initial, groundless suggestion that Winterval was introduced to avoid offending non-Christians has, particularly in recent years, become part of an ongoing campaign by sections of the media against political correctness, diversity, multi-culturalism, and the perceived Islamification of Britain. “The Winterval myth has been woven into an invented narrative that posits that Christianity and Christmas is under attack due to the intolerance of other faiths and ethnicities (in reality, Muslims), to create an inverse intolerance of other faiths and ethnicities.” (The Winterval Myth, p.4).

Which brings me back to my opening paragraph and what must seem, in the light of those that followed, the rather odd suggestion that Winterval is over. Towards the end of last year, however, just as we were approaching the normal opening of the Winterval myth season, three things happened: one in itself unnoteworthy, but the other two really rather extraordinary.

First, the Daily Mail’s polemical columnist, Melanie Phillips, in a characteristic rant on PCGM, made one of her periodic references to how “Christmas has been renamed in various places ‘Winterval’”. It was getting on for the 50th Mail article to have peddled this fiction, the single difference this time being Extraordinary Event No.1. The Mail, no doubt with the Leveson Inquiry in mind, was about to introduce a long overdue ‘Clarifications and Corrections’ policy. Which eventually – after persistent pressure from blogs like Tabloid Watch and Minority Thought, reference to the Press Complaints Commission, much resistance from the paper, and blustering libel threats from Phillips – led to Extraordinary Event No.2. It was 13 years late, will do nothing to undamage Birmingham’s reputation, and it must be doubted if the Mail was truly as “happy” as it claimed. But it did publish an actual apology, appended to a revision of Phillips’ column, “to make clear that Winterval did not rename or replace Christmas”.

So that’s it. The Winterval myth is dead. No more Winterval fiction by the Mail, Phillips and their like. And if you believe that, well, you’ll believe anything!

Chris Game

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

Catherine Staite (Director of INLOGOV)

Catherine Staite (Director of INLOGOV)