Chris Game

Devo Max – it sounds like a 99% efficient toilet cleaner, or a dodgy West Country car dealer, but either way I visualise its initials in upper case. And that’s its problem. It’s undoubtedly the ‘must use’ expression of the month. It’s not complicated, like ‘full fiscal autonomy’ or the Barnett formula, so anyone feels able to drop it authoritatively into even casual conversation. And everyone has their own idea of what it is.

For party leaders, desperate to save the Union in the final hours of the Scottish referendum campaign, it was perfect Looking-Glass, Humpty Dumpty-speak: it means just what we choose it to mean. Sign up now, check it out on Friday the 19th.

For YesScotland campaigners it was a verbal Blob, impossible to pin down and attack – and especially frustrating, as they were the ones who had no need to check it out. They knew its precise meaning because they’d invented it, and knew that it wasn’t at all what most wavering voters imagined they were being offered.

It actually originated in a 2009 Scottish Government options paper, Fiscal Autonomy in Scotland. Five distinctive options were spelt out, ranging from the SNP Government’s preferred full fiscal autonomy (FFA) in an independent Scotland to a minimally changed current fiscal framework, which gave Scotland considerable discretion over spending but little over tax revenue raising, borrowing, or broader monetary policy.

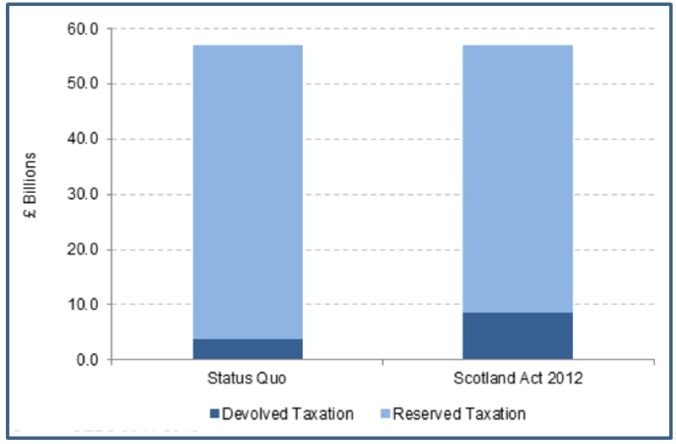

‘Devolution max’ was the SNP’s fall-back option, clearly defined as FFA within the UK. The Scottish Government would be responsible not only for most of the public spending in Scotland, but for raising, collecting and administering virtually all revenues – instead of the estimated 15% it would control even after the 2016 implementation of the 2012 Scotland Act, the famously “biggest transfer of fiscal powers in 300 years.”

The precision of its definition, as well as its content, makes Devo max entirely different from the third option of merely ‘enhanced devolution’, which really does sound vague, manipulable Humpty Dumpty-speak, and hardly surprisingly is unacceptable to the SNP.

Devo max, though, is not just definable. It can, its advocates would claim, be viewed and studied in practice, for it broadly resembles the system in the northern Spanish autonomous communities of Navarre and the Basque Country. Part of their autonomy is that the devolved governments are responsible for raising and collecting all direct taxes, including corporation tax, although, to conform with EU legislation and retain a harmonised social security system, indirect and payroll taxes remain centralised. The two regions have used their powers to lower certain taxes below the rates elsewhere in Spain, thereby creating a relatively more competitive tax regime, which is, of course, also an SNP aspiration.

The problem, as critically noted by the 2009 Calman Commission on Scottish Devolution (ch.3), is that Scotland – constitutionally, economically, as well as meteorologically – isn’t Spain. A tax-based FFA might be operable in Spain, and at least conceivable in an independent Scotland. However, attempted within the UK, it would clash with the Treasury’s expenditure-based economic model and its pooling and redistribution of taxes to fund common standards of public services and welfare benefits.

Tax experts will argue that the devolution of some additional taxes – personal income tax, land and sales taxes, alcohol and tobacco duties – is perfectly feasible and even desirable. In other cases, though, for combinations of practical, legal and political reasons, it is less feasible, and heading this list in the UK are usually the highly desirable corporation tax and the highly disputed oil and gas revenues.

In the UK, then, full fiscal autonomy short of independence is unattainable, and, even if attainable, would be effectively incompatible with the redistributive policies of our existing welfare state, and also with the controversial population-based Barnett allocation formula that all three major party leaders committed themselves to retain in their extraordinary orchestrated ‘Vow’ on the front page of the Daily Record.

So, whatever additional powers Scotland eventually gets, they won’t amount to Devo max. It might, therefore, be a good idea if we stopped trying to appropriate the label rather meaninglessly for English local government (with perhaps one exception), and looked instead to the persuasive and realistic cases already being made by those with first-hand experience of running local authorities.

By all means, use Scotland as a benchmark – as in the challenge issued by Graham Allen MP, Chair of the Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee: “I don’t see any reason why English councils are not capable of taking on the powers that go to Scotland.” And London as another. The legislation is different, but the key recommendations of last year’s neatly titled report of Tony Travers’ London Finance Commission, Raising the Capital, are both applicable to other major authorities and possibly more straightforwardly implementable – particularly the proposed control over all property taxes: council tax, business rates, stamp duty land tax, capital gains property development tax, and the like.

It’s been good this past week to see the County Councils Network, with its pre-election Plan for Government, 2015-20 and the Key Cities Group of 23 mid-sized cities with its Charter for Devolution, both determined not to have their distinctive voices and proposals drowned out by the noise of the big cities.

There’s no doubt, though, that it’s in and around the big or the eight Core Cities where the main devolutionary action is, and particularly those who’ve been able create Combined Authorities. These are legal structures set by the Secretary of State following a request from two or more English authorities and a governance review. They may take on transport, economic development and potentially other functions, and they have a power of general competence.

They were a third-term New Labour idea, and the enabling legislation – the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act – was a full five years ago now. Greater Manchester CA, bringing together 10 authorities, was first in the field in 2011 and for some time out on its own, but since April we have had four more – West Yorkshire (5), Sheffield (4), Liverpool (6), and the North-East (7). There are reports too that councils in Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Buckinghamshire, as well as the Welsh Local Government Association, are all at least considering combined authorities as an alternative to a possible future of enforced mergers.

If anything, though, Greater Manchester is stretching its early lead, with its reluctant agreement to a directly elected mayor in exchange for the “complete place-based settlement” proposed on its behalf by the independent think tank, Res Publica – “an incremental process leading to the full and final devolution of the entire allocation of public spending”. Even this, for the reasons given above, wouldn’t technically amount to Devo max, but since they already seem to have appropriated it in the cause of alliteration – Devo Max – Devo Manc: Place-based public services, it’s the one exception I’m prepared to concede.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.