Chris Game

If you’re an academic – either a genuine intellectual, theorising one, or a more lecturing, popularising one like what I was – there’s a good chance that the week before Easter is Conference Week.

It’s easy to mock, and knock, academic conferences. Too many delegates reading, rather than ‘presenting’, their papers; no time for proper interrogation, discussion and debate; mediocre university campus food. And for overseas conferences, add in climate threatening CO₂ emissions.

However, I like them – conferences, that is. Indeed, this recent Easter week I racked up a full half-century of attending, at least intermittently, PSA (Political Studies Association) conferences.

Like most such events nowadays, this one was ‘hybrid’ – with panels attended partly in person, partly digitally via Zoom. Which makes genuine discussion additionally problematic, and emphasises the importance of the written papers addressing subjects that ideally are appealing, topical and even newsworthy.

Happily, in the Local Politics Specialist Group this is almost the norm. And this year one paper especially – in addition, obviously, to that of the INLOGOV’s Director, Jason Lowther (from ‘Birminham’, according to p.25 of the evidently un-proof-checked programme!) – struck me as both sufficiently important and timely to bring it to the attention of a couple of slightly wider audiences⃰.

Timely because we’re fast approaching the May 5th local council elections, and, if these councils’ controlling parties choose to draw voters’ attention to it, many could boast something they might well not have been able to even four years ago when these same seats were last collectively contested.

Specifically, over four in every five should be able to claim that they are genuinely and actively involved in the business of delivering social housing. And if that doesn’t grab you, or you’re thinking: “well, isn’t that one of the main things councils are supposed to do?” – or maybe, as a Birmingham resident, you’ve heard of the 4,000+ homes built by the Birmingham Municipal Housing Trust, the City Council’s housebuilding arm, and assume that it’s fairly typical, rather than really exceptional – then I politely suggest you’ve rather lost the plot in recent years.

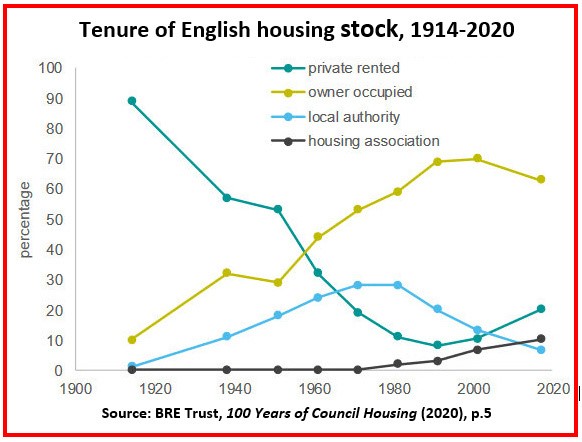

When I used to lecture to particularly overseas students about housing in England or the UK, I would use a couple of very basic graphs, similar to those illustrated here. The first showed the changing relative importance of our main housing tenures since 1919 – private rented, owner occupied, local authority, and housing association.

At the end of the First World War, the ‘big picture’ was straightforward: roughly 90% of housing stock was privately rented, 10% owner occupied. Councils were empowered to build ‘corporation housing’, but few did. But the War changed everything. PM Lloyd George promised not just houses, but “Homes Fit for Heroes’, and the 1919 Addison (Housing, Town Planning, &c.) Act facilitated it. Council housing committees sprung up, generous subsidies were provided, and council estates mushroomed.

By 1939 over 10% of the population lived in council homes, and the numbers increased steadily post-war, with the Labour Government’s Town and Country Planning and New Towns Acts. At their 1950s peak, under Conservative Governments, councils were building nearly 200,000 houses a year – one completion every three minutes, if you were wondering.

By the 1970s over a third of England’s housing stock was ‘council’. Private renting had plummeted to below 20%, with owner occupation over 50% and rising, and housing associations just beginning to take off.

The 1980s Thatcher Governments’ priorities, though, were very different: a “property-owning democracy”, with successive ‘Right to Buy’ policies – requiring, rather than allowing, councils to sell off their housing stock, if tenants, particularly of larger, better-quality properties, wished to purchase.

Coupled with Treasury restrictions on councils borrowing money for capital expenditure, there began the long-term shift from council housing to housing associations or ALMOs (Arm’s-Length Management Organisations): from 7% of all social housing in 1980 to over 60% today, including virtually all new social housing.

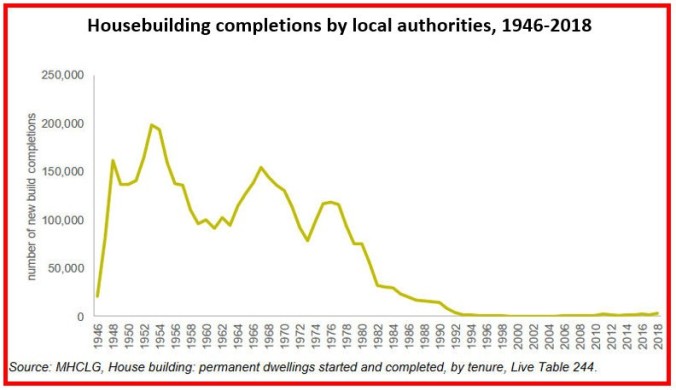

On my second graph, of ‘Housebuilding Completions’ – albeit scaled for dramatic effect – the local authority line by the mid-1990s was barely distinguishable from the horizontal x-axis. Council house building on any significant scale virtually stopped, new homes countable in the hundreds, rather than hundreds of thousands – until, if you peer extremely closely, you can just see the space between line and axis opening up in 2018.

Sales meanwhile averaged well over 100,000 a year, re-boosted by increased discounts from the Coalition Government following the 2007/8 financial crisis. That same Coalition – or its Treasury – also imposed tightly restrictive ‘caps’ on councils’ ability to borrow against their own Housing Revenue Accounts in order to build affordable homes.

True, the 2011 Localism Act and other changes gradually empowered councils to work both like and with private sector companies. But it was really only when, several years later, Theresa May announced to her October 2018 Party Conference that she would ‘ditch the cap’ that councils’ widespread re-engagement with housing provision seriously took off.

There were and still are significant hurdles: tenants’ right to buy, planning constraints, the need for more grant funding. But the climate has indisputably changed, and at least some of the circulating local election manifestos will surely contain the evidence.

The reason I’m confident of this is that one of the York conference sessions I attended was presented by Bartlett School of Planning’s Professor Janice Morphet, who, with her colleague Dr Ben Clifford, recently completed the third of their series of biennial surveys of councils’ engagement in the provision of affordable housing.

I was aware of this work, but frankly had no real idea of its scope, depth, rigour or even of the sheer quantity of data the surveys produced and made available, in both the respective main reports and the separate desk survey reports. Seriously impressive – and obviously impossible to do any kind of justice to here.

Hence the focus on what has been one of the surveys’ particularly key and consistent findings, summarised here in a couple of quotes: first from Morphet herself, then from the recent third survey’s Executive Summary:

“The third wave of research shows how local authorities are directly engaging in housing provision [and] that this has moved from a marginal to a mainstream issue.”

“From the desk survey, we found that in comparison with 2017 and 2019, the number of councils with [housing and/or property] companies … has increased from 58% in 2017, 78% in 2019 to 83% in 2021 … From the direct survey, we have found that 80% of local authorities now self-report that they are directly engaged in the provision of housing, a notable increase from the 69% … in our 2019 survey … and the 65% from the 2017 survey.”

Who said academic conferences are an indulgent waste of time?

________________________

⃰ A slightly abbreviated version of this blog – “Candidates will be homing in on a growing council priority” – appeared in the Birmingham Post on April 28th – https://www.pressreader.com/uk/birmingham-post/20220428/281951726382871

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.