Chris Game

Shortly before the dissolution of Parliament, Communities & Local Government Secretary Eric Pickles issued an apparently self-penned eulogy of his ministerial record, entitled on the Government’s own website, in characteristic, cod Churchillian, style: Local Government: Delivering for England. It makes an interesting document, as would be hoped of one requiring two separate links.

First, I want to emphasise that it’s a genuinely useful exercise. It’s already easier than probably ever before to find out what the government thinks its policy is, at any particular time, both generally and by department and topic. Currently it has 224 of them. The DCLG has 24, including four each on local government and housing, and a rather extraordinary 215 “contain ‘local self-government’”. There’s at least a Masters dissertation, surely: which nine Coalition policies failed to tick the ‘local self-government’ box?

Pickles’ eulogy, though, is quite different: a consummate politician’s listing of 60+ bullet-pointed triumphs and achievements, the like of which I at least can’t recall having for any previous administration. The gov.uk version even gives us a proxy measure of the difference – in the dozens of instances of ‘[political content removed]’. And there’s another dissertation: the insight provided by the redacted and unredacted versions into civil service interpretation of ‘political content’ in the run-up to a General Election.

None of this, however, provides more than the opening key to the main subject of this blog. Somewhere between Pickles’ 50th and 60th bullet points – shortly before “supporting the Royal Wedding, Diamond Jubilee and VE Day by cutting Whitehall and municipal red tape on holding street parties, and introducing new laws to cut ‘elf and safety’ red tape on community events” – was “localising Council Tax Support (CTS), so councils are rewarded for getting people off the dole and welfare dependency and back into work, £1 billion has been cut from previous Council Tax Benefit (CTB) funding, and councils themselves bear the responsibility of increasing the living costs of some of their poorest residents.”

OK, I’d better come clean. The ‘elf and safety’ bit is totally genuine – straight from the Pickles jar, as it were – but I’m afraid the last couple of clauses, after ‘back into work’, are mine, though, I would claim, entirely accurate and in a way slightly admiring.

For the CTB changes were Pickles’ self-styled muscular localism at its most politically skilful – a devolution of an important responsibility, impossible for councils to refuse, yet accompanied by conditions and constraints that meant any flak would go to them and any credit to the Conservative part of the Coalition.

The publication in the middle of the election campaign of the New Policy Institute’s third annual CTS monitoring report provides a timely opportunity to review one of the Coalition’s key and most controversial social policies, whose approaching launch was covered at the time in these columns.

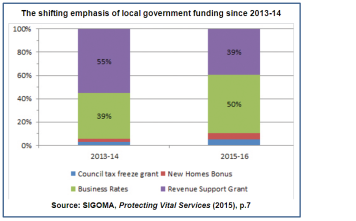

The essence of the 2012 Welfare Reform Act was to replace, from April 2013, the means-tested Council Tax Benefit, paid for by the Department for Work and Pensions but administered to nearly 6 million recipients by local authorities, by Council Tax Support schemes individually determined and operated by the authorities themselves, and funded through business rates retention. It sounded like a laudable transfer of responsibilities from Whitehall to town hall – until you came to the attached strings.

First, with the professed aim of strengthening councils’ incentives to get people back into work, the amount the Government would pay local authorities for their new schemes would be 10% less than for CTB – creating for my own authority of Birmingham, for example, a funding gap of nearly £11 million.

Second, it ruled that pensioners receiving CTB must, and other particularly vulnerable groups should, be protected against any reduction in support – meaning in Birmingham that 54,000 pensioners were protected, while 83,000 working-age recipients were left shouldering potentially the whole savings burden.

It was only here, then, that the localism bit actually kicked in, with councils having the discretion, within a very tight deadline, to devise their own schemes to achieve these savings – and collect the taxes from their tens of thousands of new and aggrieved taxpayers.

In practice, this discretion amounted to three unenviable choices: spreading the cut in funding equally across virtually all CTB recipients apart from pensioners; giving the rebate to certain groups only; or continuing with the full rebate, and filling the gap either through raising council tax or finding savings elsewhere, on top of the savings already being demanded by the Government.

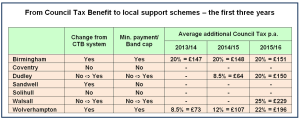

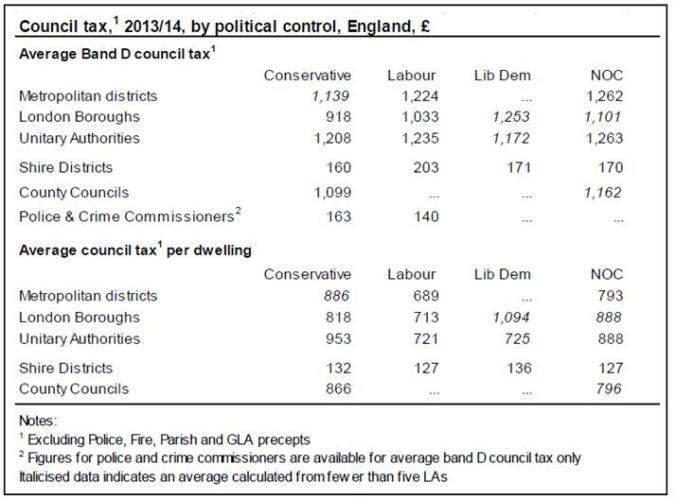

It would have been odd for a policy wholly designed to produce local difference not to do so, and there was and continues to be significant variation, in the metropolitan West Midlands as across the country. The practices adopted by the seven West Midlands metropolitan boroughs, though not statistically reflective of the national picture, can usefully illustrate it.

At that first time of asking in 2013, nearly 18% of the 326 English councils decided to continue with the same CTB-level rebate and somehow find the money, including four of the West Midlands seven.

70% of councils nationally and in the West Mids Birmingham and Wolverhampton – the two with the largest affected caseloads – introduced ‘minimum payment’ schemes, requiring everyone to pay at least some council tax, regardless of income. In Birmingham, therefore, it meant that almost all working-age people paid at least 20% of their council tax, representing an average annual payment of £147 or just under an extra £3 per week.

The remaining authorities, including Sandwell in our table, rejected ‘minimum payment’ but introduced other changes. Sandwell’s adjustments over the three years have included changing the income taper – the amount by which support is withdrawn as income increases; lowering the maximum savings limit over which one is no longer eligible for benefit; and reducing the second adult rebate – the benefit homeowners not on a low income receive if they share their home with someone (non-partner) on low income.

The main trends identified by the New Policy Institute over the now three years of CTS’ operation are the drop by nearly a third in the number of authorities still retaining all features of CTB, and the increase in percentage minimum payments – both seen in the West Midlands table. Nationally, 2.3 million low income families will pay on average £167 more in council tax in 2015/16 than they did under CTB, and 11% of those 2.3 million have also been affected by the ‘Bedroom Tax’ or ‘removal of the spare room subsidy’.

As for local councils, as is usually the case, they’ve generally coped – possibly too effectively for their own good. Some council tax collection rates have fallen fractionally, but nowhere (to my knowledge) as drastically as some predicted at the time. New council schemes to reduce worklessness are springing up all the time, but it’s difficult to identify which, if any, of these is incentivised by the CTB changes.

Something, though, is quantifiable. Roughly £1 billion has been transferred from central government’s welfare bill to the shoulders of local government – and is being borne variously by increased bills for council tax support claimants, reductions in the claimant count, increased council tax bills for all, and reductions in other council budgets. But then that’s muscular localism for you.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

An earlier version of the blog was published by The Chamberlain Files.