Chris Game

Yes, there were other news stories last weekend – Grangemouth, St Jude, Plodgate, Merkel’s mobile, Lady Gaga’s new album. Still, a more than 50% turnout in something local governmenty surely merited some kind of headline.

Last autumn, remember, the national turnout in the police commissioner elections was under 15%. Yet on Thursday, in the Cheshire village of Tattenhall, they voted in droves – not for a mayor, councillor, or commissioner, but to express overwhelming backing for their neighbourhood development plan.

From the damp squib of elected mayors to the micro-meddling of Communities Secretary Eric Pickles, the Coalition’s localism agenda has hardly been an unqualified triumph. With neighbourhood planning, though, it does seem to have hit on something capable of imbuing in at least some of us “a zeal for participation”, as Nancy Holman put it in her recent, more conceptual, discussion of the topic.

Introduced in the 2011 Localism Act, neighbourhood planning is about giving people more influence over planning decisions affecting their daily lives: choosing where new homes, shops and offices should be built (or not built), what these buildings should look like, and what infrastructure is needed.

The Act allows parish and town councils or other representative community groups (as in the Upper Eden and Exeter cases described below) to formulate Neighbourhood Development Plans (NDPs), that will shape development in their area – provided they ‘have regard to’ national policies and conform with local planning strategy.

Proposed NDPs must pass an independent standards check, usually by a planning inspector, and are then put to a referendum, organised and paid for by the local planning authority. If the Plan receives majority approval, the planning authority must adopt it, and it becomes part of the legal framework with which future planning decisions must comply.

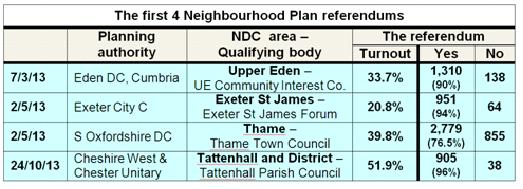

Last Thursday, in the fourth of these referendums, nearly 52% of residents turned out and 96% of them supported the Tattenhall and District NDP – which means it now has legal status? Well, not quite yet.

The NDP is a professionally prepared 30-page document replete with a vision, objectives, a strategy, implementation plan, maps, appendices, and six clear policies on various aspects of community life. But not all policies are equal, and here Policy 1 on Housing Growth is clearly more equal than the others that flow from it.

There are currently 1,090 homes in Tattenhall parish and the Plan proposes allowing up to 30 new homes in the built-up village in the period to 2030, plus some smaller scale development elsewhere in the parish. Three national housebuilders, however – Wainhomes, Barratt Homes, and Taylor Wimpey – have applied to build a total of 305 homes in what the Plan regards and rejects as “large-scale inappropriate development along existing village boundaries”.

The builders contest some aspects of the Plan and also the independent examiner’s impartiality, and the first two firms have lodged a judicial review challenge, which, until the High Court has deliberated, will prevent the Plan being formally adopted and joining what Planning Minister Nick Boles has called the quiet planning revolution.

He used the phrase back in March to describe the similarly positive outcome of the first referendum in, appropriately enough, Eden – though not the Garden thereof, but Eden Valley to the east of the Cumbrian Lake District.

The Upper Eden NDP is quite different from Tattenhall’s, not least because the area is extremely sparsely populated and about 17 times Tattenhall’s size. Again, the main focus is housing, but the proposed development rate here is 40 homes a year, and 545 over the plan period to 2025 – a higher total than the 479 in the district council plan, with all 66 extra homes allocated to rural areas that the parish councils involved in preparing the NDP felt had previously been overlooked.

Other policies include increasing affordable rural housing by permitting more conversions, incentivising developers to provide more housing for older people, and improving broadband provision. This being the first NDP referendum, there was a lot riding on it, not least for Ministers, and Upper Eden delivered. In a 34% turnout – nearly double that for Cumbria’s police commissioner vote – 90% backed the Plan.

The St James area of Exeter, site of the next plan that went to referendum, is completely different again: 6,000 residents sandwiched between the city centre and university campus in a community that has been losing its traditional and diverse character through the intrusion of traffic and car parks, neglect of green space, but particularly the conversion of family homes into houses in multiple occupation (HMOs) – student occupation.

The NDP was prepared by the Exeter St James Forum, a group of local people, including students, brought together initially by residents’ associations. Key policies included restricting the spread of HMOs and bringing more social balance to the area, encouraging small businesses, a tree planting campaign, and identifying certain residential streets for ‘home zone’ treatment with reduced and slowed traffic.

In a May 2nd vote in a student-dominated ward, turnout was an unsurprisingly disappointing 21%, but the endorsement of the Plan a positively Putinesque 94%.

The last of the four NDP referendums to have taken place so far was held on the same day, in the South Oxfordshire town of Thame, and we have another quite different scenario. For Thame’s NDP was a direct response to the core strategy in South Oxfordshire’s local plan, which proposed to allocate 600 homes on one large site on the outskirts of the town, rather than, as many residents seemingly preferred, on developable sites within the town itself.

The district council, to its credit, backed Thame Town Council’s bid for government funding to produce its own NDP, on the understanding that it could cover only non-strategic issues and not, for instance, the numbers of proposed homes. Advised by professional urban designers, the town council consulted with residents, identified more than enough potential sites, and eventually agreed on a ‘Walkable Thame’ option, the condition of which is that new homes should be within walking distance of Thame town centre.

In the May referendum it was approved by a more than 3 to 1 majority on a nearly 40% turnout. As the local media justifiably boasted, Thame residents had become the first in England to pick their own housing sites through a neighbourhood plan.

Three more referendums are currently lined up, but this is a trickle with the potential to become a flood. There are now well over 600 recognised Neighbourhood Planning Areas, and Ministers claim that over half of English local authorities are working with groups on community planning, many of whom are receiving government grant funding to help them prepare draft plans.

It’s far too early to draw any serious conclusions – as to whether neighbourhood planning will constitute a quiet revolution or anything else. But one almost instant criticism of NDPs, raised also by Nancy Holman in her references to NIMBYism, was that they would appeal most to parish and town councils in relatively less deprived rural areas in the already over-heated south-east.

It may well prove to be true, but the four very disparate Plans to have come almost arbitrarily to referendum so far offer little support.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.