Chris Game

Google “Birmingham – Britain’s second city” and you get 110,000 results; for “Birmingham – Britain’s third city” just three – all ignorant, obviously prejudiced, or both. By contrast, “Manchester – Britain’s second city” gets 895 results, only just outscoring “Manchester – Britain’s third city” with 866. QED – unofficial as the title is, if there’s going to be a second city, it’s Birmingham. Simples!

Except it’s not – not if you live and work in Birmingham, anyway. In vox pops and even proper opinion polls, Manchester more often than not edges it – and, as you may sense from the opening paragraph, we can get ever so slightly defensive about it. Which is why, if we’re offered ‘second city’ status, we generally welcome it – if only to stick it to Manchester.

Second most unequal city, however, is altogether different; and second most unequal city in the second most unequal country in Europe sounds, to me anyway, awful. Yet statistically that’s what Birmingham is.

Latest evidence comes in Cities Outlook 2013, the annual report on the economic performance of UK cities by the urban policy think tank, Centre for Cities. Now in its sixth edition, Cities Outlook is wide-ranging and influential, having played a major part in promoting the key role of cities, and particularly city-regions, as drivers of economic growth and recovery.

For policy purposes, this city-region emphasis is understandable, but it does make the title, Cities Outlook, a bit misleading. For it’s not in fact a comparative survey of 64 UK cities and their respective local authorities, but of 64 things called PUAs – Primary Urban Areas, or the built-up areas of cities, which may cover a whole bunch of authorities.

It’s fine for studying trends over time, but less so for comparing, say, Coventry and Birmingham, because Coventry PUA is the city, with its population of 319,000, while Birmingham PUA includes Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton – and a population of 2.4 million. So you have to keep remembering: ‘Birmingham’ is actually Birmingham-plus.

Though entitled Cities Outlook 2013, the report’s data were collected back when we fondly imagined we were emerging from a mere double-dip recession, rather than slithering into a triple-dip one. The report assesses how its 64 city/PUA economies weathered the two dips, which in Birmingham’s case could be described as OK-ish. Not great; we’re in the half of cities more, rather than less, severely affected in both recession periods; but there are plenty of places that economically have had it much worse.

The trouble with OK-ish is that, while it may be mildly reassuring, hovering just below mid-table in any league doesn’t get you many headlines. So I tried looking for measures where Birmingham was near the top or bottom of a table.

In itself, of course, it’s easy. In any table measuring sheer quantity, Birmingham-plus is so large that it’s got to be right up there. Not surprisingly, we have the second highest population, second highest public and private sector employment, second largest housing stock, and second grossest CO2 emissions.

Not helpful. We need things measured in percentages or ratios – like inequality. Cities Outlook uses a proxy indicator for inequality, dividing its cities into neighbourhoods with average populations of 1,500 and counting the percentages of Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) claimants in each neighbourhood. A city’s inequality is the gap between the neighbourhood with the highest JSA claimant percentage – assumed to be the poorest or most deprived – and that with the lowest.

In November 2012, the highest Birmingham-plus neighbourhood claimant rate was 24.1% and the lowest 0.4%, giving a gap of 23.7%, second only to Glasgow’s 25.4%. Obviously, there are other possible measures – household income, for example, or even personal wealth, as in last week’s other circumstantial inequality evidence, the Birmingham Post Rich List (see below). But JSA disparities are easier and less contentious. If you accept, as most statisticians do, their broad validity, Birmingham is currently the most economically unequal city in England, and second most unequal in the UK.

Though inequality isn’t directly related to size, large cities are almost bound to be more unequal than medium-sized and smaller ones, and six of the 10 largest cities are indeed among the 10 most unequal. London, though, was only 7th, Newcastle 9th, Manchester 13th and Liverpool 23rd, all with inequality gaps of less than 20 per cent. The truth is that, just as several of the smallest cities – Hastings, Gloucester, Ipswich – are by no means the most equal, the largest don’t have to be as unequal as some of them are.

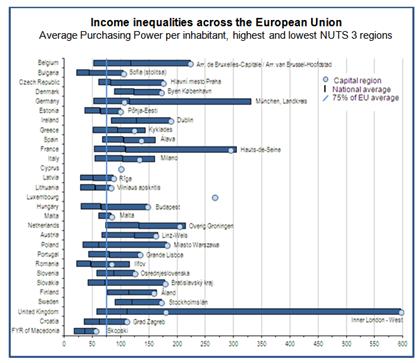

And essentially the same is true of nations. There are numerous measures of national income inequalities, and, if you’re into visual aids, one of the most vivid depictions of Britain’s extreme economic inequality is that based on the regions into which, for statistical purposes, EU nations are divided: NUTS (Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics). The NUTS 3 level comprises ‘small regions’, the UK’s 139 consisting mainly of upper-tier and unitary authorities. For each NUTS 3 region the average individual Purchasing Power is calculated and standardised (PPS), and a country’s income inequality is the difference between its highest PPS region and the lowest.

Source: Office for National Statistics

The UK national average PPS is 110.6, that in the highest region (Inner London – West) 596, and in the lowest regions (Wirral and West Wales) 57 – a tenfold inequality that is almost twice that in Germany and France, three times that in Italy and Spain, and five times that in Denmark, Finland and Sweden.

Dramatic as these ratios are, it should be emphasised that they are derived from workplace, rather than residential, data: individuals’ incomes are related to where they work, not where they live. The much more widely used measures of national income inequality are those based on the Gini coefficient or ratio, developed by the Italian sociologist, Corrado Gini. He was Mussolini’s favourite statistician, with some dubious ideas about nations having life cycles, and ‘young’ nations fulfilling their destiny by expanding at older nations’ expense, through a combination of wars and cross-breeding with younger races.

Happily, his stats were less flaky, and the Gini coefficient of national income distribution is widely used around the world, generally based in more developed countries on disposable, post-tax income. Data are collected through household surveys, and the coefficient runs from a hypothetical zero or perfect equality, where everyone has exactly the same income, to a similarly hypothetical 1, where one person has the lot.

In the latest statistics published by the 34-nation OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), the overall coefficient is 0.31, and the range extends from Slovenia (0.24) and Denmark (0.25), through the US (0.38) and Turkey (0.41) to Mexico (0.48) and Chile (0.49). Taking the EU-27 alone, highest is Portugal’s 0.35, closely followed by the UK on 0.34.

So Birmingham is the second most unequal city in the second most unequal country in the EU – which doesn’t altogether surprise me, but certainly isn’t something I’d want to celebrate. Nor the OECD, who are pretty clear what their figures represent: “High income inequalities typically imply a waste of human resources, in the form of a large share of the population out of work or trapped in low-paid and low-skilled jobs.”

Yes, I can see that, but then I’m not one of the 50 on the Birmingham Post’s West Midlands Rich List, published by pleasing coincidence in the same week as Cities Outlook. The net worth of the lucky 50 rose last year by just the 13.8% or £3.46 billion. That’s right, the single-year increase of these 50 mainly-male Midlanders alone equalled Birmingham City Council’s total budget, or roughly half of the real-terms funding loss of all English councils put together over the 2011-15 spending cycle.

Which, say our business leaders, is “very good news … [for] with wealth creation goes job creation and this is to be applauded.” You can almost hear Thatcher, can’t you: “Our job is to glory in inequality”. Remember the trickle-down theory? The rich perform a public service by getting richer still, because their prosperity would automatically trickle down to the poor. There are many still waiting for that trickle to reach them, and who must be relieved that the City Council’s ‘living wage’ policies at least sound as if they make sense.

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.