Chris Game

Well, that was fun – the Daily Mail’s high-speed impression of the Grand Old Duke of York. In Monday’s first edition we were marched to the top of the hill, to glimpse a vista of a snap May 4th General Election, a Prime Ministerial Brexit mandate, and a three-figure Conservative Commons majority stretching way into the distance. And by the lunchtime edition we’d been marched down again, accompanied by much harrumphing about unfounded rumour-mongering.

With not calling an early election being among the few subjects on which Theresa May has been utterly consistent, the surprise would have been if she had. And my sole reason for raising it here is that, whatever its macro-political effects, a synchronous General Election would have significantly increased the likely turnout in the six metro mayoral elections, and consequently enhanced the profile, legitimacy and general political clout of both the new office and its first incumbents – all currently at a premium.

In the metropolitan West Midlands, then, we’re not going to see on May 4th the probably 60-65% turnout that was the 2015 General Election figure. That would have enabled the new mayor, in his or her meetings with ministers, to claim to be representing not only nearly 2 million electors, but perhaps 1 million who had actually participated in their election. Which in turn would make it that smidgen harder for the centre to cut local funding and resist further devolution, rationalising that few vote for and therefore care about their local government.

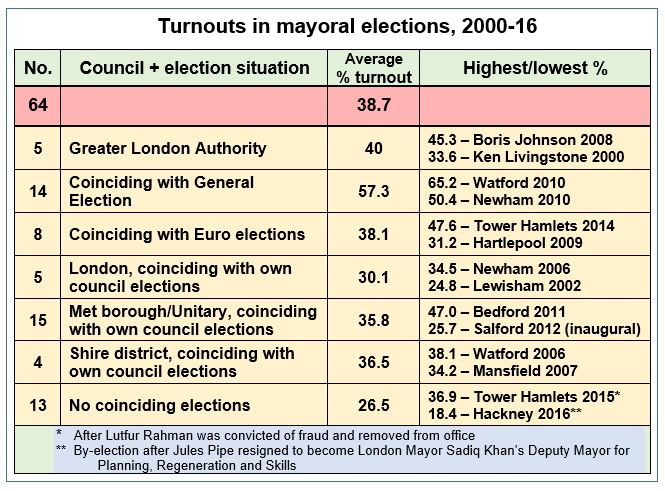

But now that’s off, what can we expect? A former student asked me recently – more or less a true story! – what the average turnout had been in all mayoral elections since Ken Livingstone’s first election as London Mayor in 2000. 38.7%, I told him, or thereabouts. He was surprised – and less by the confirmation that I was indeed one of those seriously sad people who know such things than by the figure itself. And of course he was right to be.

He fancied putting a bet (in the low-20s) on the percentage turnout on May 4th, when in the four metropolitan and unitary Combined Authorities (CAs) – West Midlands, Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, and Tees Valley – there are no other significant elections taking place. This year in the electoral cycle is shire county year, which should boost the mayoral turnout a bit in Cambridgeshire & Peterborough and West of England, but won’t help the others.

If only I’d had my table with me, I could have shown my ex-student how that overall 38.7% masked the relatively respectable turnouts when mayoral polls had coincided with other elections, and particularly a so-called ‘first-order’ national (General) election, when voters reckon considerably more is at stake.

But when ‘only’ a mayoralty has been the prize – merely the elected political leadership of one’s city, town or borough – turnouts have been almost unexceptionally feeble. And those have been in established local authorities, familiar to electors, rather than new, huge, amorphous, unelected bodies that most voters have barely heard of.

And the situation gets worse. Most voters with at least some awareness of metro mayors fondly imagine these new politicians foisted upon us will have powers to do the things that we think are most urgent and would like them to do. Tough!

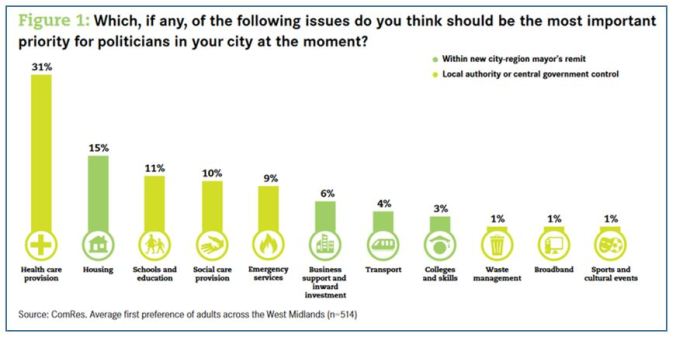

In last May’s Centre for Cities/ComRes poll – still the most comprehensive on metro mayors – of the five issues West Midlands respondents felt should be the priorities for politicians in their city, only one, housing, was something that would be among the responsibilities devolved either to a West Midlands metro mayor or even the Combined Authority.

Aspects of health and social care, education, and emergency services may possibly be devolved in the future. But on May 5th most of the mayor’s attention will go to business support and inward investment, transport, and colleges and adult skills that only about one in 20 possible voters have as their priorities.

It’s a big disjunction and on the face of it a recipe for yet further voter disillusionment. And a major dilemma for those who genuinely believe that elected mayors represent the best chance we’re likely to have of decentralising serious power to England’s localities and regions: how to ‘big-up’ the potential of metro mayors without misrepresenting and overselling them.

I have neither the answer nor much space, but I was struck this week by the Institute for Government’s latest ‘Local Leadership event’ – ‘How will new mayors work with Whitehall to improve their city-regions?’, and particularly the encapsulation of the IfG’s mayoral case by its Director of Development, Dr Jo Casebourne.

Emphasise, she suggested, these mayors’ difference from either existing or previously rejected mayors; that they’re leaders of place – of functional economic areas, not councils; able to provide visible, legitimate and accountable leadership and wield ‘soft power’, with better access to ministers and to other public sector bodies across their regions; and outward-looking and future-focused, able to attract inward investment and, working with other mayors, to secure, as in London, more devolved powers, both functional and financial, in the future.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.