Chris Game

An unambiguously positive title, I trust you’ll agree – not least because I plan to stick a gentle boot in later on. We must start, though, with full credit where it’s due. This weekend, the Green Party of England and Wales celebrates its 40th anniversary – a remarkable achievement indeed for a party that, in its own folklore anyway, owes its origins to a guy in Coventry picking up a Playboy magazine.

The Coventrarian was Tony Whittaker, a solicitor and onetime Conservative councillor, and the story goes that his eye was caught and his political inspiration sparked not by Playmate of the Month, but by an interview with the American biologist, ecologist, and population alarmist, Paul Ehrlich. Now it so happens that 40 years ago I, like Professor Ehrlich, was working for Stanford University, California, and I remember distinctly that his Playboy interview had appeared some three years earlier, in 1970, shortly after the publication of his controversial book, The Population Bomb. I conclude, therefore, that either Whittaker was a serious Playboy collector and addict, or the Ehrlich interview played a somewhat less singular role in Green Party history than is sometimes suggested.

Whatever. What is indisputable is that Whittaker and some likeminded associates were alarmed by Ehrlich’s doom warnings of population growth threatening the Earth’s delicately balanced environment and ultimately human survival. Despairing of Britain’s existing political parties even seriously acknowledging the problem, they resolved, at a meeting on 23rd February 1973, to form a new one. Its initial name was simply People, but by the time of the two 1974 General Elections it had morphed into the People Movement – albeit a modest-sized one. Suffice to report that in February its six candidates’ combined 4,576 votes constituted statistically 0.0% of the total, and in October it was rather less successful.

Time for a more meaningful name, and in 1975 the Ecology Party was founded and almost straightaway won its first council seat, in Rother, East Sussex. It also acquired a high-profile spokesperson in (now Sir) Jonathon Porritt, and under his chairmanship election performance improved dramatically, membership rose to over 5,000, and it could lay genuine claim to be “the fourth party in UK politics, ahead of the National Front and Socialist Unity”.

By now, though, ‘Greenness’, previously associated largely with the Greenpeace environmental movement, was becoming more party politicised. Actual Green parties were emerging across Europe – Die Grünen in Germany, Les Verts in France – and in 1985, partly to avoid being outflanked, the Ecology Party underwent another name-change to the Green Party, initially UK-wide but since 1990 just of England and Wales, there being separate parties in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

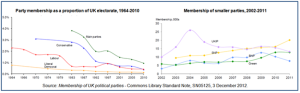

By most measures of party vitality, the Greens’ record over the past quarter-century would be judged one of steady, if frustratingly gradual, progress. As shown in the graphs below (http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN05125), in an era in which membership of most major parties in most western democracies has been declining, Green Party membership has grown more or less uninterruptedly from 5,000 in 1998 to a 2011 count of 12,800. Its parliamentary vote has increased at each election since 1997, and 2010 saw party leader, Caroline Lucas, returned as the first Green MP.

Despite never again reaching its spectacular 15% vote share in the 1989 European Parliament elections, the party has had 2 MEPs since 1999 and has increased its vote at each five-yearly election since 1994. Three Greens were elected to the first London Assembly in 2000, and the party’s gradually increasing representation on principal councils is currently approaching 150. This includes running the unitary Brighton and Hove Council as a single-party minority administration, and Lancaster City Council as part of a Labour/Green coalition. And, at least as important as it must sometimes be irritating, it has received the double-edged compliment of seeing Green ideas and policies permeate, or blatantly appropriated by, the so-called mainstream parties.

There can be no serious doubting, then, that anniversary congratulations are well in order. There is, however, a ‘however’. I note that the Greens, perhaps with their celebrations in mind, are again claiming to be the fourth party in UK politics – and, reluctant as I am to rain on the parade, I respectfully beg to differ. That reluctance is increased by the fact that a close INLOGOV colleague, Professor John Raine, somehow manages to double as an industrious Green councillor, and so it is with particular apologies to John that I suggest that the Greens’ bid for fourth party status, notwithstanding all that gradual progress, is probably less persuasive today than when it was originally made back in the 1980s.

It may be the party itself senses the holes in its case, for it talks of having “up to a million supporters in this country, and tens of millions across Europe” – John Vidal, The Guardian, 18 February 2013 – . Supporters are good, especially in large numbers, but they’re slippery customers – not reliably countable and cashable, like subscribing members, voters, or elected representatives. If your case rests on alleged supporters, it’s shaky.

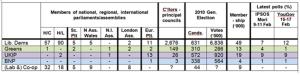

A Green bid for fourth-party status based on the data in the accompanying table would rest to an extent on Caroline Lucas in the Commons, its sister-party members in the Scottish Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly, and its record in successive Euro-elections, but above all on its local government representation – hugely exceeding that of UKIP, who have no more than three members on any single council.

No minor party does well out of first-past-the-post parliamentary elections, but, leaving Ms Lucas aside, UKIP in recent elections has fielded considerably more candidates and gained far more votes. In fact, in 2010 the BNP too fielded more candidates and won more votes. UKIP’s Euro record is also much the superior, its membership has consistently been and is today significantly higher, and, certainly at present, it’s closer in the opinion polls to challenging the Lib Dems than it is to being headed by the Greens.

I reckon therefore that, unless you give extra weighting to councillor representation – a pleasing idea, I grant you – UKIP’s case is overall the more persuasive, though definitely not as compelling as its website would have us believe, as, on the back of a few striking by-election results and opinion polls, it promotes itself as “the UK’s third political party – and the only one now offering a radical alternative”.

One final thought. In preparing the above table it occurred to me that, depending on the criteria you use, there is arguably another candidate for the UK’s fourth largest party, and one almost certain to increase its visibility over the next few years: the Co-operative Party. We tend not to think of it as a party in its own right, but, apart from the minor snag of not fielding its own candidates in UK elections, it has all the other attributes of the legally separate party that it is: a leadership structure, membership subscriptions, local branches, an annual conference, and a distinguished history dating back to the First World War.

It is the political arm of the co-operative movement and since 1927 a sister party to Labour – the two parties working jointly to promote, among various shared aims, co-operative working and other forms of mutual organisation. This joint-working includes an electoral alliance, under which the parties put forward and partially fund the election expenses of ‘Labour and Co-operative Party’ candidates – 44 in the 2010 General Election, of whom 28 were elected, including Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, Ed Balls.

As the table shows, there are also Labour and Co-operative Peers, members of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, and, says the party, “hundreds of councillors”, although the latter are difficult to count, as in multi-member wards the party must endorse all candidates before they are permitted to use the designation on ballot papers. Whatever the number, they are definitely increasing – including in the Greens’ proverbial backyard of Brighton and Hove, where Labour councillors became the first to change their name officially to the Labour and Co-operative Group. Others have followed suit, and, as Labour nationally and locally starts seriously embracing ideas of mutualism and co-operation, the sister party must be sensing something of a new dawn. So make the most of your 40th anniversary, Greens – only four years to the centenary of the Co-op Party.

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.