Catherine Durose

EHRC research exploring the under-representation of women and other groups protected under the Equality Act (2010) has been used to support a call for the Coalition to act to address the issue of women’s representation in Parliament. Women from the Political Studies Association’s Women and Politics group challenge the government to accept the logic of sex quotas and introduce legislation for elected institutions in Great Britain.

In the call for legislative quotas, researchers from the PSA women and politics group argue that if local parties are worried about having local candidates they can recruit and support local women to stand for selection. Supporting more candidates locally can have the benefits of reducing the costs (and barriers) of candidature and election and can potentially ‘open up’ politics to a wider range of people, as well as reinforcing the constituency link in national politics. As the Councillor’s Commission suggested, one way to do this is to encourage more civic and issue-based activists into politics. Such activists bring not only important skills but also an authenticity currently seen to be lacking in politics.

The Call

Claire Annesley, Rosie Campbell, Sarah Childs, Catherine Durose, Elizabeth Evans, Francesca Gains, Meryl Kenny, Fiona Mackay, Rainbow Murray, Liz Richardson and other members of the UK Political Studies Association (PSA) Women and Politics group.

This last week has seen the issue of women’s representation in Parliament hit the headlines, once again: Samantha Cameron apparently lamented the lack of women in politics to her husband; mid-week, job-shares for MPs were put forward as a new way to increase the number of women in the UK Parliament and there have been calls for quotas for the National Assembly for Wales. Over the weekend the Liberal Democrats launched two inquiries into the alleged sexual harassment of prospective women candidates and this Monday the 2013 Sex and Power Report was published, documenting the ‘shocking’ absence of women from all areas of public life. The findings of Sex and Power may be ‘shocking’ but they did not come as a shock to feminists. Enough is enough, it’s time that the Coalition Government stepped up and implemented the recommendations of the 2008-10 Speaker’s Conference on Parliamentary Representation. It should follow the evidence commissioned by Parliament, accept the logic of sex quotas, and introduce legislation, for Westminster and other elected institutions in Great Britain.

Party leaders have said it before, and no doubt they’ll say it again: In the words of David Cameron:

“Companies, political parties and other organisations need to actively go out and encourage women to join in, to sign up, to take the course, to become part of the endeavour”.

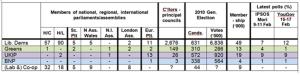

The problem is that exhorting women to participate in politics will never address the ‘scandalous’, as Cameron also put it, under-representation of women at Westminster. Men are nearly 80 % of the House of Commons. Women are not even half-way to equal presence. Labour does the best with a third of the Parliamentary Labour Party female. The Tories at 16 percent, come second, and they did more than double their number at the last election. The Lib Dems trail in last, at just 12 percent, with fewer women candidates and fewer women MPs in 2010 than in 2005.

The situation is depressingly familiar at other levels of government in the UK. Despite Nordic levels of women’s representation when the Scottish Parliament and the National Assembly for Wales were first created, the overall trends are of stalling or falling with campaigners calling for legislative quotas in devolved and local government and for the Speaker’s Conference to be replicated.

Fewer women than men currently want to be politicians – we need to address the reasons why and make sure that there is greater diversity overall in Parliament – but the most pressing problem is not with women but with the political parties and their willingness to select and support the qualified women who would like to stand in seats where they have a good chance of winning. Cameron himself acknowledged this last week:

“Just opening up and saying ‘you’re welcome to try if you want to’ doesn’t get over the fact that there have been all sorts of barriers in the way”

These multiple barriers were examined extensively in evidence given to the specially convened Speakers Conference which looked at how to improve the diversity of representation at Westminster. Only some of its recommendations have since been introduced. One key recommendation was that candidate selection data be routinely published so the public can see who was being selected by the parties. Unfortunately the Coalition has opted for a voluntary approach to the publication of this data. In its absence, political parties will likely get away with shifting the blame onto women when what is at issue is their failure to recruit women.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission’s evidence to the Speaker’s Conference was just one of many to identify the barrier of party demand: a perceived gap between the rhetoric for equality of representation by national party elites and the reality of decision making at the critical point of candidate selection on the ground. EHRC research shows local parties frequently opt to pick candidates who fit an archetypal stereo-type of a white, male professional. The Conservatives, Labour and Lib Dems choose to address this particular barrier in different ways – with only the Labour party addressing it by using a party quota, All Women Shortlists. Yet, the Speaker’s Conference recommendations were clear that in the absence of significant improvements in 2010, Parliament should consider legislative quotas. There was no such significant increase. And looking forward, there is, if anything, talk of declining numbers of Conservative and Liberal Democrat women in 2015.

The global evidence on quotas is clear: well designed and properly implemented quotas are the most effective way to address the under-representation of women. Shouldn’t the Government follow the evidence? Other measures can and do make some difference. It is why we support the call for MP job-shares; the training for women candidates that all parties provide; and diversity training for party selectorates, amongst other measures. And it’s why we welcomed the Conservative Party’s A list at the 2010 general election, even if it could not guarantee the selection of greater numbers of women. But the gains across the board have just been too slight and are taking too long.

The Coalition could – if it really wanted to – act on this issue now. Introducing legislative quotas – making all political parties implement quotas – would give the two party leaders ‘political cover’. Both leaders’ positions on quotas are on the record: they gave commitments to the Speaker’s Conference in person. Clegg said he wasn’t ‘theologically opposed’ and Cameron said he would use some AWS before the last election, although in the end he didn’t. And we are pretty confident that Labour would support legislative quotas: how could it not given its own record on this issue?

We acknowledge that hostility to quotas is out there, but criticisms can be challenged. Quotas are not the electoral risk that some activists suggest. Studies show that being an AWS candidates does not cause electoral defeat. If the principle of merit troubles, one can counter that current selection processes are themselves not meritocratic. Cameron said so himself. Nor do quotas produce unqualified or poor quality women MPs – few know which of Labour’s 1997 intake were selected on AWS, and they were equally as successful in terms of promotion. And we simply don’t buy the argument that there are not enough qualified women out there – each party has its ‘folder’; and if it is perceived to be a bit thin, some good old fashioned searching will find more. Evidence from the US shows us that party demand begets a greater supply. The Government can also make other changes to increase the supply of potential candidates – let’s give the House more professional hours and ensure that families can afford to live and work in both London and the constituency, for example. Finally, and for some the bottom line, is criticism of what local parties regard as top-down measures. But if the truck is with ‘outsider’ women ‘being imposed’ then local parties can recruit local women to stand for selection.

Candidates are being selected as we write – the time to act is now. So, Messers Clegg and Cameron, be constitutionally radical (there’s not been too much success so far here) and leave a legacy of gender equality from the Coalition Government. Let’s have a House of Commons that closer approximates the sex balance of the UK in 2015. You could, at a minimum, set up a Second Speaker’s Conference with the remit to implement the recommendations of its predecessor and to work with other parliaments and assemblies across the four nations. Or be even more bold: to expedite women’s representation the Government need only introduce a Bill establishing legislative sex quotas. The alternative is for us to wake up the day after the 2015 election and find the party leaders once again bemoaning the continuing under-representation of women at Westminster.

This post was originally featured on the PSA Women and Politics blog.

A shortened version of this post was also published by the Huffington Post.

The EHRC research cited here was led by Catherine Durose (University of Birmingham) with Liz Richardson, Francesca Gains, Ryan Combs and Christina Eason (University of Manchester) and Karl Broome (University of Sussex).

The work has also been cited in the recent report of the Communities and Local Government Select Committee, ‘Councillors on the frontline‘.

For further discussion of these findings see Durose, C., Richardson L, Combs, R., Easton, C., and Gains, F. (2012) ‘Acceptable Difference’: Diversity, Representation and Pathways to UK Politics. Parliamentary Affairs.

Catherine Durose is Director of Research at INLOGOV. Catherine is interested in the restructuring of relationships between citizens, communities and the state. Catherine is currently advising the Office of Civil Society’s evaluation of the Community Organisers initiatives and leading a policy review for the AHRC’s Connected Communities programme on re-thinking local public services.