Two research-based reports on electoral reform appeared almost simultaneously last week. Great for anoraks, but for a local government blog a dilemma. Only one report directly concerns local government, and here, therefore, it properly leads off. But the second is – how to put this – at least methodologically the more interesting and will receive the greater attention.

Northern Blues: the Conservative case for local government reform is an Electoral Reform Society (ERS) report. The case starts from the Conservatives’ proportional under-representation – indeed, frequently complete non-representation – on northern metropolitan and unitary councils, due to the workings of the plurality or First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) electoral system. This weakens the party’s base for fighting parliamentary elections and undermines its claim to be a genuinely national party. The most obvious remedy, the report suggests, would be to follow the Scottish switch to the Single Transferable Vote (STV) form of proportional representation for local elections, which since 2007 has given Conservatives seats on councils and even in cabinets, where previously their presence was minimal.

None of this, of course – apart from the supporting statistics – is remotely new, even to Conservatives. Conservative Action for Electoral Reform (CAER), for example, is 40 next year, and jointly sponsored the oddly unmentioned 2005 forerunner of this report: Lewis Baston’s The Conservatives and the Electoral System.

The statistics do demonstrate the party’s under-representation on nine northern metropolitan councils in the three most recent sets of elections, but they are less “compelling” than the report’s foreword suggests, due to elections by thirds not being treated as individual events (p.8), and the omission throughout of total membership sizes of the councils on which the Conservatives are under-represented.

Simpler statistics and, I’d suggest, more compelling are that: (1) in the 2011 elections, in which the Conservatives overall did tolerably well, in the eight metropolitan boroughs of Gateshead, Knowsley, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, Sheffield, South Tyneside and Wigan, the party’s candidates won an average of over 11% of the vote, but not one seat; and (2) today, of the total of 606 members on those same councils, just two are Conservatives (South Tyneside and Wigan, if you were wondering).

We know all about the Tories being the rich and nasty party, but sometimes overlooked is their stupidity quotient – as noted by John Stuart Mill to a Conservative MP in one of history’s great “I was misquoted” apologies: “I never meant to say the Conservatives are generally stupid. I meant to say that stupid people are generally Conservative”. Sadly, even Peter Osborne, Telegraph and Spectator journalist and author of the ERS report’s above-mentioned foreword, is no exception to the rule. As blind as most of the party to the self-harm of its obsessional commitment to FPTP, Oborne claims “reading this report has persuaded me that proportional representation in local elections may be part of the answer” to the question of how to stem the wipe-out of Conservatism in northern England. It’s only one convert, but who knows?

Back in the world in which the rest of us live, we have Divided Democracy: Political inequality and why it matters – published by the ‘progressive’ thinktank, the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). It’s a fascinating study of non-voting and its consequences that might almost have been devised to rebut the more objectionable views that the comedian, Russell Brand, has been inflicting on us recently.

Among Brand’s addictions are four-syllable words: he’s “utterly disenchanted”; politicians are all frauds and liars; the political system is merely “a bureaucratic means for furthering the augmentation and advantages of economic elites”. Until a “total revolution of consciousness” appears on a ballot paper, he will never vote – non-voting being “a far more potent political act to completely renounce the current paradigm”.

Pretty obviously, it’s not potent at all, but it’s his next pearl that really gets me: “I will never vote, and I don’t think you should, either … it seems like a tacit act of compliance”. He wants us to join his misguided personal tantrum, and that is objectionable.

If self-interested economic elites are your enemies, it’s NOT VOTING that is the tacit act of compliance, consenting to their authority and perpetuating their rule. Not voting is a delusion: you either vote by voting, or you vote by abstaining and doubling the value of an opponent’s vote. Inaction has its own consequences. Multi-millionaire Brand can afford to be careless of the consequences of his inaction. Potential non-voting disciples may not all be as fortunate.

The IPPR counter-thesis is simply summarised. Turnout in UK elections is not just falling, but is becoming more unequal. Governments aren’t stupid: they note these trends and act on them. They privilege voters, discriminate against non-voters, thereby ratcheting up societal inequality – at present, massively. One obvious way of making such behaviour at least more politically risky is through full or selective compulsory voting.

First, the figures. Recent General Election turnouts have fallen dramatically: from nearly four-fifths of the electorate in the 1960s to below 60% in 2001 and 65% in 2010. The fall has been anything but equal: much higher among the youngest and poorest. In 1970 the turnout gap between 18-24 year olds and over-65s was 18%; in 2010 it was nearly double: 76% of over-65s voting, but only 44% of 18-24 year olds. As for income, if you divide electors into five income groups, in the 1980s turnout among all five groups was over 80%. In 2010, while over three-quarters of the highest income quintile voted, turnout among the lowest quintile was barely half.

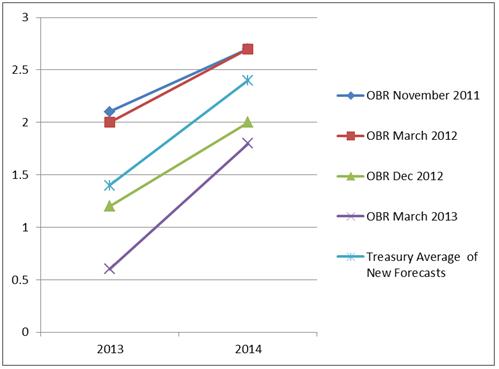

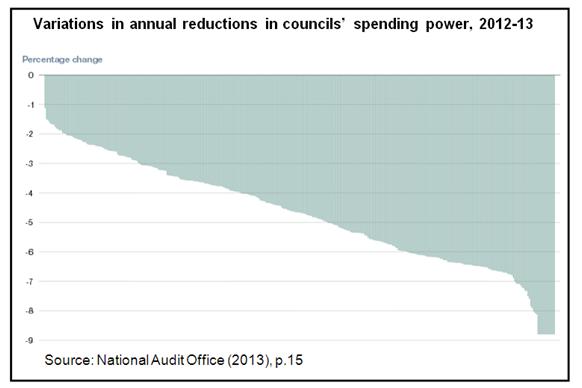

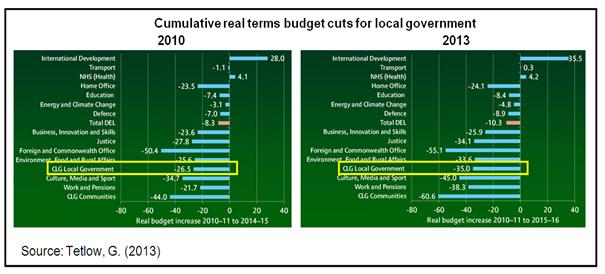

Any rational government, knowing these unequal turnout statistics, would in its own self-interest pay more attention to the likely voters than to the non-voters. The IPPR authors’ major contribution is to have developed measures of the extent to which the Coalition has acted in this way during its three years of cuts-driven austerity. In short, have low turnout groups suffered disproportionately from the funding reductions announced in the 2010 Spending Review and the national and local public service cuts to which they led?

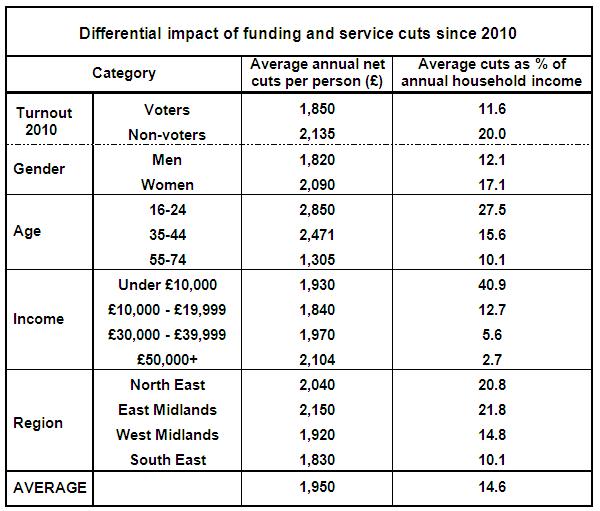

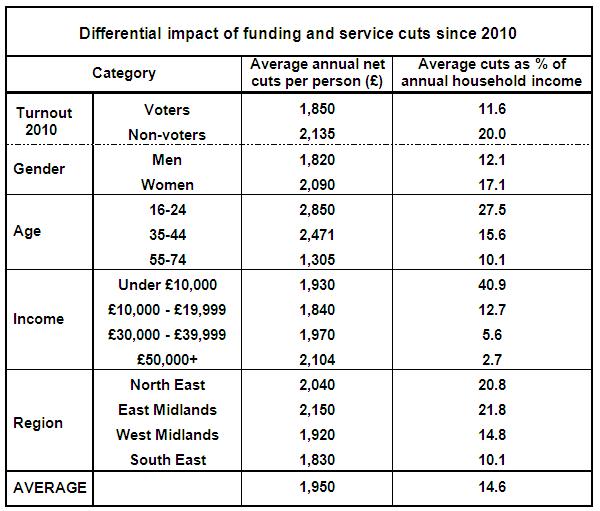

As the summary table shows, the answer is unmistakably Yes. The methodology, fully described in the IPPR paper, is complex, but uses the Treasury’s own accounting framework to collapse all public service expenditure into hundreds of small, everyday items, and then allocate them to households on the basis of known household consumption and spending patterns. Essentially the same is done for individuals, using information about voters and non-voters collected by the 2010 British Election Study.

The table confirms that all groups have been adversely affected to some degree, but that there are clear political inequality effects: women suffering a greater annual loss in services and benefits than men; the young more – much more – than the middle-aged and elderly; some regions more than others. Considered as a proportion of the average household income, the differences are even starker, especially in the case of income level itself. To quote the researchers: “Those with annual household incomes under £10,000 have lost an average of £1,926 annually from the spending measures, comprising a staggering 40.9 per cent of their average income”.

These are clearly important statistics in themselves, but the IPPR study’s primary concern is with the political inequality effect in respect of voters and non-voters: the cuts representing at household level 11.6 per cent of voters’ annual income and 20 per cent of that of non-voters.

Governments may not systematically aim to discriminate against non-voters, but that is the irrefutable effect of their policies – the inevitable consequence being “a vicious cycle of disaffection”. The less responsive politicians seem to be to their interests, the more disaffected people become, the less inclined they are to vote, and the less incentive politicians have to pay them attention.

The IPPR is already on record as a supporter of compulsory voting, as already practised in around a quarter of the world’s democracies. Even where not very robustly enforced, it produces significantly enhanced turnout rates – particularly among likely non-voters, thereby drastically reducing turnout inequality. Recognising, though, that a proportion of UK citizens tend to be fiercely protective of their right not to vote, the present authors settle for the more limited measure of making electoral participation compulsory for first-time voters only.

They would be obliged to go to the polls once, on the first occasion they were eligible – at their place of study for students living away from home. A ‘None of the above’ option would be available, as in many compulsory systems, and it is suggested that a small fine be set as a gentle persuader.

There are several ancillary arguments for first-time compulsory voting. It should encourage voting in subsequent elections, boost citizenship awareness and political education, but above all it would force politicians to pay more attention to young people and their interests than they are inclined to do at present. Oh yes, and it’s infinitely more constructive than anything Russell Brand has to offer.

Chris is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.