Liam Hornsby

Whilst the concept of place perception has been studied by academics since the 1990s, it is only recently that local authority-led place brand narratives have started to emerge. There has been a wealth of academic literature on the drivers of place brand narratives and the impact that they have on perception. Despite publicly accessible guidance available for local authorities recommending the development of a place brand narrative, however, there remains a gap in research related to the tangible benefits that can be derived from the development and establishment of such an approach.

This research project explores the tangible benefits of place brand narratives for local authorities, using Watford Borough Council as a case study. It investigates key drivers for establishing place brand narratives, such as tourism, inward investment, and business growth, and develops measures to evaluate their impact through quantifiable data. The research concludes that place brand narratives can significantly enhance socio-economic outcomes.

Key points

• Place brand narratives can lead to improved town centre footfall, visitor economy, commercial property occupancy, resident employment, enterprise growth, reduced crime perception, and enhanced resident happiness.

• Political and resident buy-in is crucial for successful implementation of place brand narratives.

• Authenticity in the narrative is important.

• Place brand narratives can justify investment in their development, despite the challenges of stretched council budgets and prioritization of investments.

• The study acknowledges limitations such as reliance on qualitative data and potential bias from data provided by local authorities with vested interests.

Background

The perception of a place is crucial for the prosperity of towns and cities. Recently, local authorities have leveraged social media and digital tools to strategically shape public perception of their areas. This effort, once limited to major cities and tourist spots, now sees many councils developing place brand narratives to attract investment, boost tourism, and enhance civic pride. However, research on the tangible benefits of these narratives has been scarce.

This study aims to fill that gap by quantifying the benefits, providing local authorities with data to support investments in place branding. The research demonstrates a link between place perception and benefits such as increased town centre footfall, improved visitor economy, resident happiness, reduced crime, and higher inward investment. By comparing these outcomes to national averages, the study seeks to justify the investment in place brand narratives, even amidst budget pressures and the need for long-term rather than quick solutions.

What we knew already

The study of place brand narratives has evolved from early 1990s concepts of linguistic place-construction, where language was seen as a tool to enhance place appeal. Initially, the focus was on how names and labels could change people’s perceptions of a place. Over time, scepticism grew about the effectiveness of mere name changes in altering perceptions – it became clear that just renaming places isn’t enough to change people’s views significantly. Instead, modern approaches emphasise the need for creating a robust narrative that tells a compelling story about the place that highlights its history, achievements, and future potential.

Effective place branding should connect with both residents and outsiders, gaining support from the community and political leaders. It’s important for the narrative to be realistic and recognizable to those who live and work there. However, research on their quantifiable benefits is limited, highlighting a gap in understanding the effectiveness of implementation versus development.

What this research found

In order to find reliable links between place brand narratives and benefits, this research collected data from 277 local authorities from across the United Kingdom using Freedom of Information requests. Of these, 57 responses indicated the existence of a place brand narrative in their locality and identified specific benefits as part of the business case. From the responses, a sample group of five councils with similar populations sizes and socio-economic indicators was selected to further explore in detail the benefits that can be expected from place brand narratives.

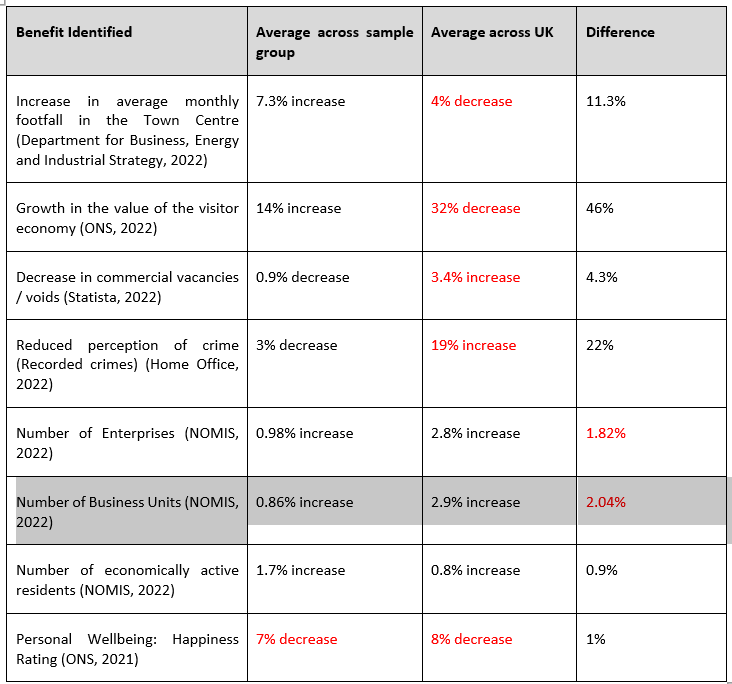

The identified benefits

What do these results indicate?

The sample group of local authorities with place brand narratives performed variably compared to UK averages. While the number of enterprises and business units grew, they did not match the national average, suggesting limited impact on business growth.

However, in other areas, the sample group outperformed the UK average. These authorities saw smaller decreases in resident happiness and commercial property voids, a significant reduction in recorded crimes, and greater increases in economically active residents. Notably, they experienced substantial growth in the visitor economy and footfall, likely influenced by increased domestic tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected international travel.

This suggests that places with brand narratives recovered more quickly from the pandemic’s economic impact. Despite mixed results for business growth, the overall positive performance in other areas underscores the potential benefits of place brand narratives. The results further indicated that significant sums of money are not required to leverage benefit. Rather, the success of the place brand narrative could be in the way it was developed and implemented.

Conclusions

This research concludes that there is a positive relationship between place brand narratives and various benefits for local authorities. Councils investing in these narratives can expect increased tourism, footfall, and economically active residents, along with reduced crime and fewer commercial property vacancies. Although the impact on business growth metrics is less clear, none of the areas studied saw a decline.

This study supports the business case for place brand investment, aligning with commentators who advocate for its benefits and providing political justification crucial for success. Local authority managers can use these findings to make informed decisions, conduct benefit-cost analyses, and allocate budgets effectively during challenging financial times. Further research is recommended to explore the development and implementation of place brand narratives and their long-term benefits. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic effects suggest that repeating this research in the future could provide even more accurate insights.

About the project

This research was a Master’s dissertation as part of the MSc in Public Management and Leadership, completed by Liam Hornsby and supervised by Dr Timea Nochta.