Chris Game

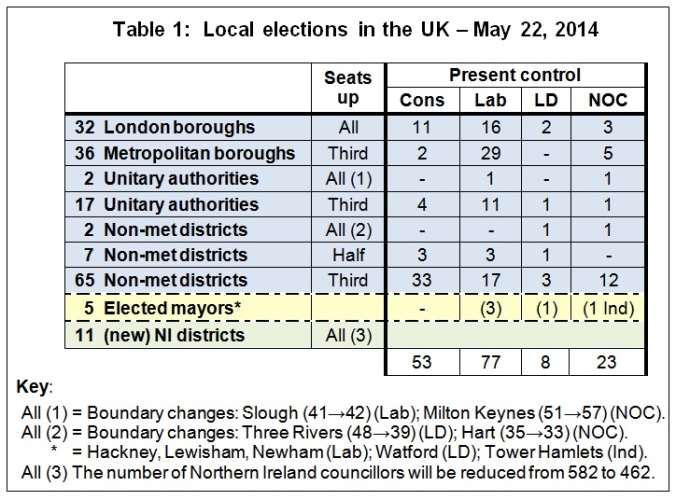

Two EU countries this May will hold local elections that coincide with their European parliamentary elections: Greece and ourselves. On Sunday 25 May Greeks vote in the second, ‘run-off’ round of elections to all their 13 regions and 325 municipalities. England, though nearly five times as populous as Greece, also has 325 lower-tier and unitary authorities. We, however, will elect mostly only fractions of fewer than half of our councils, yet still it takes seven lines of a table to summarise the 161 authorities whose voters on Thursday 22 May will probably have both a local and Euro vote. We bemoan our disappointing local turnouts, but we don’t make the system exactly voter-friendly.

Inevitably, the Euro elections will dominate the campaign, and the all-out London borough elections will dominate the local results. In this preview too – though less so in the longer INLOGOV Briefing Paper – all-out elections are accorded priority.

May 2010, when most of this year’s retiring councillors were elected, was Labour’s second worst parliamentary election performance in 80 years. Given a different context, though, its local and particularly its London election performance would have been justifiably celebrated – three boroughs won directly from the Conservatives (Ealing, Enfield and Harrow), seven more from No Overall Control (NOC), and more London seats than the Tories for the first time since 1998.

There’s no mystery about the national-local discrepancy – just two big reasons: the four-year electoral cycle and the General Election-boosted turnout. The seats up in 2010 were those contested in 2006, when Labour’s estimated 26% of the national vote barely topped the Lib Dems’ 25% and was way adrift of the Conservatives’ 39%. By 2010 that 13% national vote gap had halved, bringing big Labour gains in both votes and councils – thanks partly also to hugely increased turnouts of over 60%, benefiting the large parties, especially Labour, at the expense of minor ones.

Of nearly 1,600 minor party and independent candidates in London, just 23 were elected: 2 Greens, down from 12 in 2006 (Camden, Lewisham); 1 Respect, down from 15 (Tower Hamlets – now 2); no BNP, and no UKIP – though the party has since reached double figures, mainly through Tory defections. This year turnouts will be down again, and minor party representation – including, but not only, that of UKIP – equally certainly up.

London is not a UKIP priority, and its best prospects may be in those boroughs where it already has defectors – Hounslow, Merton and Havering (from the Conservatives), Barking & Dagenham (from Labour). But UKIP influence – countrywide but particularly in London, where electors have potentially three local votes – will also be more subtly felt through vote-splitting, helping Labour to gain control, or possibly the Lib Dems to retain it, where they might not otherwise have done so.

With its long-term opinion poll lead, though, it is again Labour that will be expecting to win councils as well as seats. Back in early January, Sadiq Khan, Shadow Minister for London, announced the party’s ‘suburban mindset’ strategy, and its five Outer London ‘battleground boroughs’ – Conservative-controlled Barnet and Croydon, and the currently hung Harrow, Merton and Redbridge.

The latter are the proverbial low-hanging fruit. In HARROW Labour actually won a majority in 2010, but then, as described in a blog at the time, lost it through splits and defections, handing control to the current Conservative minority administration. In MERTON it took minority control, strengthened it through Conservative defections to UKIP, and achieved a good result in last summer’s Colliers Green by-election. In REDBRIDGE the Conservatives and Lib Dems signed a partnership agreement just as their leaders were doing the same at Westminster. In all three boroughs Labour will be aiming for majority control, in Redbridge for the first time ever.

In CROYDON the Conservatives narrowly retained a 4-seat majority through an electoral system rewarding nearly 19% of Lib Dem voters with no councillors at all. Here too a modest swing would give Labour an equally workable majority, and more than justify the party’s decision to employ a full-time agent.

BARNET, though, seems an altogether tougher proposition. Numerous issues have incensed residents – from the ‘One Barnet’ mass privatisation of council services, through the closures of libraries and children’s centres and the scrapping of sheltered housing wardens, to the ever-contentious increased parking charges. But Labour has never won more seats than the Tories, and to do so would require a nearly 10% swing plus the Lib Dems clinging on to their three very marginal Childs Hill seats.

Labour’s last listed London target is the TOWER HAMLETS mayoralty, held by the controversial Independent and Labour expellee, Luftur Rahman. Opponents have accused him of everything, from dubiously selling off and granting planning permission for the hotel conversion of the listed Poplar Town Hall to trying to buy his own re-election, but little of the mud really seems to stick and it may, if anything, boost his support. Panorama recently had a go, following which Eric Pickles sent in his inspectors – though not to report back until well after the May elections.

The other four mayoral contests all involve incumbents who were elected in 2002 and are now seeking their fourth consecutive terms: Jules Pipe (Hackney), Steve Bullock (Lewisham) and Robin Wales (Newham), all Labour, plus the Lib Dem Dorothy Thornhill in WATFORD. All four have their policy initiatives and successes, but only Thornhill can claim in addition to have totally recast the politics of her town and council. Watford in 2002 was an apparently permanently Labour-run town. Yet its voters chose as their mayor a Lib Dem councillor and assistant head teacher, whose party coattails have since transformed the council chamber to the extent that two-thirds of members today are Lib Dems.

Returning to London, with the Lib Dems’ local election performance having collapsed almost as grimly as its national poll ratings, the party’s two majority-controlled London boroughs are bound to be under scrutiny. SUTTON they’ve held since 1990 and, although they lost one councillor to Labour, arithmetically at least they look safe for another term. In KINGSTON UPON THAMES, though, with one councillor resigning to sit as an Independent, plus a lost by-election following their disgraced leader’s imprisonment, their 2010 six-seat majority now hangs on a single seat – and on the hope that UKIP may take votes from the Conservatives in the right places.

The other all-out elections are those caused by boundary reviews, two resulting in slightly enlarged unitary councils and two in smaller district councils. MILTON KEYNES has been run in the recent past by all three major parties, and since 2011 by a minority Conservative administration. Labour will be aiming to become at least the largest party on the new, enlarged council. SLOUGH, it is totally safe to say, will continue to be Labour. In THREE RIVERS the Lib Dems will seek to maintain the majority control they’ve held since 1999; and in HART Labour will be wistfully recalling when it last won even a ward – in 1976.

Of the 36 metropolitan boroughs, Labour already controls 29 and so has little need of a target list here. Of the two Conservative councils, TRAFFORD looked the more vulnerable even before the recent shock resignation of Matt Colledge as both council leader and councillor. Having reduced the Tories’ majority to 3 in a recent by-election, Labour will hope to win its own for the first time since 2003. The SOLIHULL Conservatives look securer, partly because their principal challengers, the Lib Dems (now 9), have been defecting to the Greens (now 7), who will be seeking to supplant them as the official opposition.

The West Yorkshire trio of Bradford, Calderdale and Kirklees have all been hung since at least 2000, but this could be about to change. In BRADFORD Labour’s 2012 hopes of turning its minority control into a majority were thwarted by the coattails effect of George Galloway’s parliamentary by-election victory for Respect. The coattail councillors all resigned last October to become Independents, and Labour should make it this time.

KIRKLEES and CALDERDALE travel in parallel. Five years ago, both boroughs were run by Conservative minorities, which were replaced by Labour-Lib Dem coalitions, which were succeeded in turn by Labour minority administrations. In both boroughs all three main parties have groups numbering at least double figures – a measure of the difficulty any one party has in trying to win an overall majority. Arithmetically Kirklees looks the more attainable for Labour, but the party would probably have to take seats from the Conservatives, Lib Dems and Greens. In Calderdale, in the wards being defended that require swings of less than 10% to change hands, Labour is unlikely to be the chief beneficiary, having finished in second place in 2010 in just three to the Conservatives’ ten.

In STOCKPORT, the Lib Dems now have only minority control of their metropolitan flagship, and are defending 12 of their 29 seats. Labour is the leading opposition, but, having finished second in only two of them in 2010, its gains may be limited. Already the largest party in WALSALL, its chances should be better. If it won the same wards as in 2012, but without this time losing a couple of others to Independents, the party could gain majority control for the first time this century.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.