Chris Game

In choosing to announce the 2015-16 local government finance settlement just eight days before Christmas, ministers presumably hoped – as, indeed, I’d expected – that the argument about the presentation of funding and spending cut statistics for local authorities, both collectively and individually, would have died away by mid-January. However, it hasn’t, which is why I too am returning to the topic, which had its importance re-emphasised several times over the past week. First, Paul Woods, until recently Newcastle’s long-term and respected Treasurer, expressed in a Local Government Chronicle column (13 Jan.) his disappointment at the widespread:

“Acceptance being given to a low 1.8% spending power cut, as opposed to the more realistic analysis by the Chartered Institute of Public Finance & Accountancy (CIPFA) of a 6% cut. A truly independent and objective analysis of the settlement … would be unlikely to conclude that spending power has only been cut by 1.8% … [or that] as the government has claimed, the settlement is fair to north, south, urban and rural areas”.

That last ‘claim’ was a direct quote from the opening paragraph of an article that Local Government Minister, Kris Hopkins, had evidently felt it necessary to write for the same magazine (LGC 12 Jan.). Not surprisingly, it largely reiterated points from his settlement announcement – including that “councils facing the highest demand for services continue to receive substantially more funding … than authorities facing less pressure”, and that, for pooled budgets like the public health grant, “it would be perverse not to consider [all] the money as part of the funding available” to local authorities, including that actually spent by the NHS. Then, last Friday, we had the open letter from Rob Whiteman, CIPFA Chief Executive, to DCLG’s new Permanent Secretary, Melanie Dawes. After congratulating Dawes on her appointment, Whiteman attempted quite a barbed lecturette on “ethics in government”, including the need for “greater clarity” in the department’s public communications, as opposed:

“to the rhetoric and spin that has too often characterised the presentation of the numbers by DCLG and others over the past few years … [meaning that] … the public are being misinformed about official information and data. For example, describing transferred resources that still must be spent on the NHS as increasing councils’ ‘spending power’ in a way that under-reports their loss of DCLG grant is disingenuous.”

Given these developments, it seemed worthwhile using these columns – in which it is possible to include both links/references and a couple of rather striking graphs – to explain a bit more fully, if very definitely non-technically – what this dispute is about.

Grants and grant funding can seem both bewildering and paint-dryingly boring. But, at our combined average age of ten, my younger sister Jennifer and I didn’t know this, and we reckoned we’d cracked at least the essential principles – which was fortunate, as we and our mum were even more heavily grant-dependent than today’s metropolitan borough councils.

In our traditional patriarchal household, my father was the sole wage-earner, and he funded my mother through her weekly (Friday) ‘housekeeping’ grant, and us children through our weekly (Saturday) pocket-money grants. Opportunistically, through grandparental charity or the undertaking of ‘errands’ (mainly me) and ‘chores’ (J), we could increase our revenue spending power. But we could also suffer largely non-negotiable grant-loss, to pay for the upkeep of J’s pet rabbit, a cricket ball-broken window, or – seasonal touch here – Christmas gifts for the afore-mentioned grandparents.

The point is that, callow as we were, we understood perfectly the distinction between grant funding and spending power – unlike the sections of our media who either parroted or headlined not the finance settlement’s actual words – let alone its meaning – but DCLG ministers’ political message. ITV was typical: “the amount of funding councils will get in central government grants will be reduced by 1.8% in 2015-16”.

That’s what ministers hoped we’d hear, but for them the F-for-funding word has become as unmentionable in company as the Old English F-expletive. ‘Amount of funding’ is much too coarse, measurable and comprehensible. It’s far more refined – and cryptic – to talk of spending power (SP), particularly if you get to define it yourself. What minister Hopkins announced, therefore, was that “the average spending power reduction for councils in 2015-16 is just 1.8%”. Indeed, with “the additional transformation money the government is giving councils to improve services, this reduction falls to 1.6%” (emphases added). See, it’s getting even better. Moreover:

“Those facing the highest demand for services continue to receive substantially more funding. For example, Middlesbrough has a spending power per household of £2,441, which is £871 more than the £1,570 per household in Windsor and Maidenhead.”

This is the fifth year in which ministers have attempted this sleight of hand, and, to be fair, most of the media have caught on. Most did report that the 1.8% cut is not in councils’ grant-funding, but their spending power – though still only a minority explained the distinction and its significance.

It would have been like my father deciding in one of the 1950s’ sterling crises that we should all (kids included) be in it together, and imposing a three pence austerity cut in my pocket money of two shillings and sixpence (2/6 = 30 pre-decimal pence) – but overlooking that he’d already cut it by sixpence for cricketing misdemeanours, which I’d subsequently made up through errand work. As he might have explained, it was only a 10% reduction in my spending power, not the 12.5% grant cut I was claiming. Besides, he knew of better-off families in Westcliff (SE Essex’s nearly-as-posh equivalent of Windsor and Maidenhead) whose children didn’t even get weekly pocket money.

Following the Coalition’s ideological decision to reduce the budget deficit largely but selectively through public spending cuts, local government ministers in 2010-11 faced the problem of explaining to the public that they’d be cutting central government grant funding of council revenue spending by an unprecedented 28% in cash terms (40% in real terms, allowing for inflation) over four years, with 21% ‘front-loaded’ in the first two years.

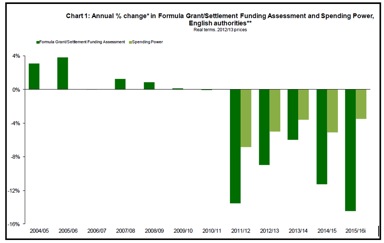

The scale of ministers’ task can be seen in a simple but powerful chart in a recent House of Commons research paper, in which the dark green columns represent the savage annual average percentage cuts in councils’ grant funding, in contrast to the generally modest increases to which they’d been accustomed. Their solution: to replace the nasty dark green columns with much less alarming light green ones.

First, they – or their civil servants – restructured the whole grant system, to make before-after comparisons more difficult. They then created their Revenue Spending Power measure, which they claimed would – by including council tax receipts, certain specific grants, and NHS social care funding – give a fuller picture of a council’s overall financial position.

First, they – or their civil servants – restructured the whole grant system, to make before-after comparisons more difficult. They then created their Revenue Spending Power measure, which they claimed would – by including council tax receipts, certain specific grants, and NHS social care funding – give a fuller picture of a council’s overall financial position.

Fuller, yes, but not full. Contrary to what is stated in the Government’s Plain English Guide to the 2015-16 Grant Settlement (para. 3) income from fees, charges and investments is NOT included in SP. These are income sources likely to decline in a recession and whose addition to SP would emphasise, rather than de-emphasise, councils’ grant dependency – so nothing like as politically helpful as the contrived SP measure, which could instantly reduce a 28% grant cut to a 14% cut in spending power.

Ministers, then, view SP in the same way as Humpty Dumpty in Alice Through the Looking Glass. It can mean just what they choose it to mean – or more, or less. If, say, they excluded council tax receipts from SP, any percentage grant cut would immediately become more (bad). If, on the other hand, they could include the whole of the new Better Care Fund (BCF) – a single pooled budget to incentivise the NHS and local councils to work more collaboratively – any cut would immediately become less (good).

Yes, of course it’s confusing; that’s its whole point. Present the public with two, three or more magnitudes of ‘spending power cuts’, and the chances are we’ll either turn off altogether or hear the one that’s shouted loudest: the Government’s. For 2015-16, as we’ve seen, the Government’s figure is 1.8% – or possibly 1.6%.

Neither the figures nor ministers’ form of presentation came, by this time, as a surprise, and the Local Government Association (LGA), attempting to get its retaliation in at least simultaneously, released its own figures to coincide with ministers’ announcements. These showed first that the Government’s total funding support to local authorities will be cut by 13.7% from the 2014-15 figure. It’s that F-for-funding word again, so ministers didn’t bother mentioning it, but it’s shown as a provisional figure in the Commons chart.

The LGA’s second calculation was that, if council tax income were excluded from SP – since it’s a completely different type of income from government grant – the average reduction would be not 1.8%, but 3.7%. Third, if you also exclude the NHS’s portion of the £3.5 billion Better Care Fund and include in SP only the estimated £2 billion spent on social care services by local authorities, the arguably rather truer average reduction in councils’ revenue spending power becomes 8.8%, or nearly five times the Government’s figure.

CIPFA’s analysis, as we’ve already seen, was different again: a 6% drop in spending power – through including council tax income but excluding ring-fenced grants and the Better Care Fund. To adapt the old Punch cartoon caption: you takes your choice of definition, but you still loses your money.

And that spending power cut, to repeat, is the average for all English local authorities – and even under the Government’s SP figures, individual authorities could lose up to 6.4% of their spending power, though others would receive a nice little increase. But, especially with a General Election imminent, ministers like Kris Hopkins want to persuade us that their settlement “offers a fair deal to taxpayers all over the country; north and south, rural and urban. Councils facing the highest demand for services continue to receive substantially more funding and have about 40% higher spending power than authorities facing less pressure.”

That last sentence really is disingenuous. Any formula or block grant comprises both a redistributive element, to compensate for local authorities’ differing needs, and a negative ‘resources’ element, to reflect their differing ability to raise their own money through council tax. Even this government hasn’t contemplated abolishing the redistributive principle altogether. But let’s see how it judges that its way of doing things offers a ‘fair deal’ to taxpayers, regardless of where they live.

Again, I’ll start personally. I pay my council tax to Birmingham City Council, whose cut in spending power, according to the Government’s figures, is 6%, close to the maximum 6.4%. Cuts for other West Midlands metropolitan authorities run from Sandwell (5.1%) and Wolverhampton (5%), through Walsall (4%), Coventry (3.9%) and Dudley (2.8%) to Solihull – the sole Conservative-controlled council and, as it transpires, the only one whose SP will increase (+0.4%).

So Birmingham’s cut is proportionately the greatest, despite, as noted in Sir Bob Kerslake’s recent highly critical report on the council for the Government, having “more poor children than anywhere else in England” (p.6), and being overall one of the most multiply deprived authorities in the country.

According to the DCLG’s ranking of England’s 326 local authorities by multiple deprivation – Birmingham is 13th most deprived, Sandwell 9th, Wolverhampton 20th, Walsall 35th, Coventry 53rd, Dudley 113th, and Solihull 212th – almost precisely the same order as that for percentage SP cuts and, on the face of it, a non-obvious operationalisation of a ‘fair deal’.

Local Government Chronicle and the Association of North East Councils undertook a similar exercise on a larger scale, again using the Government’s SP measure. As shown in the chart, “the most deprived 10% of areas face a 5.2% cut while the most affluent tenth will see their funding rise by 1.5%”.

With apologies for the length of this blog, that’s what this particular local-central argument is fundamentally about – a little more than just the niceties of statistical presentation.

With apologies for the length of this blog, that’s what this particular local-central argument is fundamentally about – a little more than just the niceties of statistical presentation.

An earlier Birmingham-focused version of this post appeared in The Chamberlain Files

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.