Chris Game.

“Cornwall leapfrogs West Midlands in devolution race” was the headline over one report of the Government’s recent devolution deal with Cornwall Council, giving the county greater control over adult skills spending and regional investment, and, with the Isles of Scilly, the prospect of integrating health and social care services.

For a West Midlands resident it seemed a depressing message – almost depressing enough to make one contemplate shooting the messenger. However, I happen to know him, so I’ve settled for shooting his metaphor, and in doing so providing a further update of events that could bring what I described in a previous blog as the most significant power-shift in English government in generations.

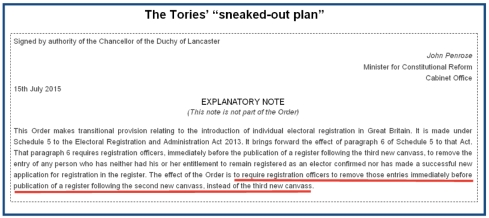

First thing to concede is that, predictably from this wholly centralist and Osborne-choreographed devolution exercise, it absolutely is set up as a race – certainly against time. It was outlined on p.63 of the Summer Budget’s Red Book:

“To fulfil its commitment to rebalance the economy and further strengthen the Northern Powerhouse, the government is working towards further devolution deals with the Sheffield City Region, Liverpool City Region, and Leeds, West Yorkshire and partner authorities, to be agreed in parallel with the Spending Review.”

We’ll return to the detailed wording later. The point here, apart from the redundant reminder of the Chancellor’s tunnel-visioned insistence on an elected mayor as the only acceptable accountability mechanism, is the Spending Review deadline, repeated a few paragraphs later:

“The government remains open to any further proposals from local areas for devolution of significant powers in return for a mayor, in time for conclusion ahead of the Spending Review.”

This week, a fortnight after the Budget and just seven summer holiday weeks before his chosen submission deadline, the Chancellor realized it would be useful for others to know the relevant Spending Review dates. Its conclusions, we learned, will be outlined on 25 November. But deal-seeking councils need to check p.15 of another Treasury document:

“City regions that want to agree a devolution deal in return for a mayor by the Spending Review need to submit formal, fiscally neutral proposals and an agreed geography to the Treasury by 4 September 2015.”

Numerous race analogies suggest themselves – obstacle, hurdle, handicap – but I see the devolution race less as a single race and more like the London Marathon – several races taking place simultaneously with different categories of participants starting off from different places at different times.

Take Cornwall. As the first rural council to negotiate a devolution deal, it clearly deserves credit, and doubtless its methods are being studied closely by other counties rushing to recruit partners and submit bids by the Chancellor’s deadline.

These county areas, though, are effectively in a different race from the big city regions. Their bids will vary greatly, in scale and aspiration, and in London Marathon terms their equivalents are perhaps the ‘Good for Age’ racers, who secure guaranteed entry by running a specified time considered good for their age group. They’ll hopefully win the appreciation of their friends and residents, but the big prizes will inevitably go to the Elite runners, the 150 miles a week guys, who need a certified 2 hours 20 time just to qualify, and sub-2 hours 10 to get into the serious prize money.

In the devolution race there’s only one elite entrant even to have glimpsed serious fiscal devolution-type money – Greater Manchester. The region starts with natural advantages, with its geographical and political coherence, and its 10-council team of runners was first out of the blocks in 2011, in applying to become the first Combined Authority (CA).

Moreover, they run as a team, agreeing to accept the race sponsor’s favoured elected mayor along with all that devolved funding, and now the prize money keeps arriving on a regular basis – most recently on Budget Day, when they won £30 million funding for ‘Transport for the North’ plus control of the fire service, Land Commission, children’s services and employment programmes.

Following the elite runners in the London Marathon are the Championship entrants – registered members of an athletics club, with a certified 2 hours 45 race time. The devolution equivalent is the exclusive Combined Authority club – still just the five members, those joining Greater Manchester being, to give them their official names, West Yorkshire, the North East, and the Sheffield and Liverpool City Regions.

West Yorkshire, Sheffield and Liverpool are actual or, in Liverpool’s case, near reincarnations of the areas’ 1972-86 metropolitan counties, and in that sense similar to Greater Manchester. The North East CA is different – hugely bigger than the former Tyne & Wear met county, but having at least the coherence of covering the same area as the North-East Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP).

As we have seen, the three former met county CAs were all name-checked by George Osborne in his Summer Budget speech – though few seemed to notice the precise names he used: “the Sheffield and Liverpool City Regions and Leeds, West Yorkshire and partner authorities” (my emphasis).

Having undertaken a serious resident and stakeholder consultation exercise back in March, North East leaders were rather peeved not to have made Osborne’s list. Since then, though, they’ve moved fast – not exactly embracing, but at least dropping their outright opposition to, an elected mayor, and opening talks on a “radical devolution deal” with Communities Secretary Greg Clark.

Temporarily at least, therefore, this might seem to put them ahead of Sheffield and Liverpool, but what exactly is happening in West Yorkshire? How is Leeds – unlike Birmingham, which has to make what noise it can under the ‘West Midlands’ banner – apparently managing to retain its nominal identity in its devolution deal?

Prior to the election, it was assumed that big city devolution deals would be negotiated with, where they existed, Combined Authorities. But then, in late June, Greg Clark delivered his remarkable eulogy to LEPs. These partnerships between business and councils were evaluated recently by the Royal Town Planning Institute as having “an opaque remit”, lacking “firm institutional foundations”, and being overly responsive to central government direction. In the new minister’s view, however, they represent:

“a phenomenal revolution [that has] completely changed the way investment and growth is done in this country. The areas that combined authorities are now following are the same areas defined by LEPs as being the true economic geography of our nation. As such, no devolution deal will be signed off unless it is absolutely clear that the LEPs will be at the heart of arrangements” (my emphasis).

Anyway, whoever’s verdict you prefer, LEPs are where Leeds City Region comes in. A city region is an economists’ and planners’ term to describe the functional region around a city – its ‘true economic geography’, as Greg Clark might put it. The label dates back at least to Derek Senior’s Memorandum of Dissent in the 1969 Redcliffe-Maud Report. But institutionally not much happened until the arrival in the late-2000s of Multi-Area Agreements (MAAs) – voluntary agreements between a number of local authorities and the government to work collectively to improve local economic prosperity.

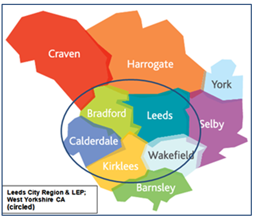

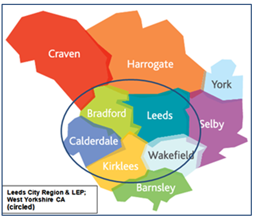

There were eventually 15 of them. Of the big cities, those for Greater Manchester, South Yorkshire, Liverpool, and Tyne & Wear took the forms their respective CAs now do. But, instead of West Yorkshire, there was Leeds City Region, as shown in the accompanying map: the five former West Yorkshire metropolitan county boroughs, plus Barnsley from South Yorkshire, and Craven, Harrogate, York and Selby from North Yorkshire.

MAAs were formally wound up by the incoming Coalition, but in practice most, like Leeds City Region’s, accompanied their authorities into their new LEPs. Which explains why West Yorkshire’s devolution bid is focused, as the Chancellor convolutedly but correctly described, on ‘Leeds, West Yorkshire and partner authorities’, or, more succinctly, Leeds City Region.

Not surprisingly, Birmingham also had a Multi-Area Agreement and a city region partnership, but in its case the emphasis is firmly on the past tense. It went under the catchy name of the Birmingham, Black Country and Coventry City Region and produced, among other things, an MAA for Employment and Skills. But it was short-lived, with Coventry soon opting out to concentrate on developing its links with Solihull and Warwickshire.

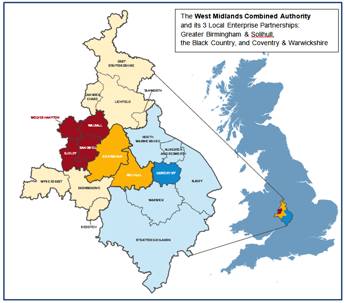

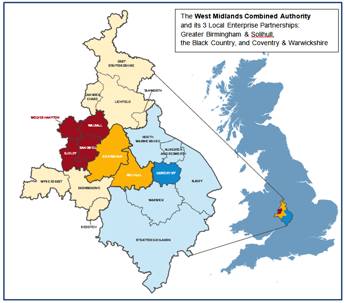

And there’s Birmingham’s devolution problem in a nutshell: no convincing city region. Instead of the pubescent MAA partners developing together, perhaps with the addition of adjoining authorities, into a single LEP corresponding to Clark’s ‘true economic geography’ of the city region, it split instead into three: Greater Birmingham & Solihull, which struggles to look convincing even on the map, the Black Country, and Coventry & Warwickshire.

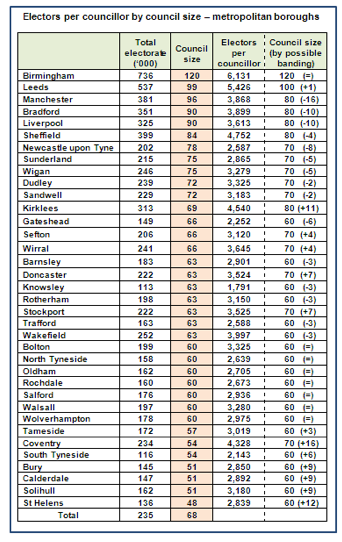

The present situation is – how to put this – not exactly setting pulses racing. We have a recently, and for some unenthusiastically, agreed proposal for a Combined Authority of the seven former West Midlands metropolitan council boroughs – Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and, Wolverhampton – to run transportation, regeneration and economic development.

It clearly can’t claim, in Greg Clark’s words, to have any of its three LEPs “at the heart of arrangements” – although that could change with the possible addition of some or more councils in Warwickshire, Worcestershire and Staffordshire – a state of uncertainty that Police & Crime Commissioner David Jamieson, the West Midlands only elected official, described this week as “an absolute dog’s breakfast”.

Finally, far from it having been agreed that the CA should have accountability through an elected mayor, it apparently won’t have any individual leadership at all. Apart from numerous commitments to “collaborative working”, the Launch Statement has nothing to say about governance, although the understanding is that each council leader will take responsibility for an individual policy portfolio.

Returning to the London Marathon analogy, Greater Manchester obviously crossed the Mall finish line some time ago, has donned its foil blanket, collected its Virgin Money finishers’ medal, and is heading back up the M6. Several others are on that home stretch between Big Ben and Buck House, but it seems the WMCA still has some miles to go to reach the Embankment.