Chris Game

In Catherine Staite’s recent blog – ‘Devolution: a journey into the unknown?’ – she noted that the big differences between, say, New Labour’s numerous central-local projects and the way Combined Authorities (CAs) and devolution deals are being stitched together (yes, I think that’s the right term), are the Treasury-charged power dynamic and the resulting pace of change: “If DCLG tries to drive change, it is at the mercy of the Treasury. When the Treasury drives change, it happens.”

For understandable reasons – for, like the Treasury, she too had goodies to offer – Catherine swiftly moved on: “So what next?”. Having no goodies myself, I shall stop off for at least a brief stocktake of what has become a key recent theme: the role of the citizen and voter – or the lack of one – in this whole devolution business.

In my previous devolution blog I compared, with much help from the Local Government Chronicle, the range of functions and services covered in the 30+ English CA devolution bids. These bids aren’t public documents, but I assumed at least most of the bigger and seriously ambitious CAs would have chosen – even though I knew my own hadn’t – to make decent summaries of their bids accessible to any residents curious to learn what powers were being sought in their name.

We now know, thanks this time to the Municipal Journal, just who has and hasn’t chosen to publish. MJ researchers found that almost a third of CA bids submitted aren’t accessible to even the most enthusiastic of their more than 21 million residents. The population figures made a good strapline, helped by their including all three GB capital city CAs, but it was the explanations/excuses of the non-publishers that made the most interesting – in every sense – reading.

London simply couldn’t be bothered to offer a comment. And Cardiff, like a virgin gambler thinking George Osborne might find it amusing to play bluffing games with local authorities, described its bid as “more like an opening gambit with the Treasury”.

Then there was Greater Manchester. Given the devolutionary leadership role the CA and its predecessors have rightly earned, it sounded almost a betrayal to hear Manchester City Council leader Sir Richard Leese pronounce that “We don’t think [the bid] has much business in the public domain while it’s still in the development stage”.

There seems so much wrong with this hoarding approach that it’s hard to know where to begin. It’s élitist, insulting, alienating, divisive and, certainly not least, counterproductive. For, as Catherine Staite noted to the Local Government Chronicle, it reinforces the Treasury’s top-down, divide-and-rule approach to the whole devolution process, leading CAs to tailor their bids and measure their ‘success’ with reference to what others have got, rather than what is in the best interests of their particular areas and communities.

Thankfully, spokespersons for the published bids took strikingly different views – like John Sinnott (CE, Leicestershire): “All partners believe it is important to be transparent about their intentions – both ahead of and during the negotiations.”; Nicola Beach (CE, Greater Essex): “I think it’s really important that we are transparent on this because it’s a partnership approach. Communication is important, so we’ve put as much detail into the public domain as we can.”; and Joe Anderson (Elected Mayor, Liverpool): “I don’t see why anyone would want to keep it secret.” (Joe Anderson, Elected Mayor, Liverpool).

Well, Joe, the West Midlands CA is one that very definitely wants to – and, moreover, to outsource responsibility for doing so. Its spokesperson (anonymous) claimed: “We’re not allowed to release the documents. The Treasury told us we cannot publish it.” Which a Treasury spokeswoman (equally anonymous) promptly denied: “Regions are free to decide whether they want to publish the documents or not. We haven’t told anybody not to go public with the bid.”

This was subsequently confirmed by the recipient of the most recent devo deal, Tees Valley CA, whose Chair, Sue Jeffrey, confirmed in the same LGC article that “Nobody ever said ‘You can’t talk about it.’ It was more the nature of the way the process was done … people were feeling their way.”

As, of course, are the rest of us – frequently in the dark. Still, it left the West Midlands as the only non-publishing CA suggested by the Treasury to be telling porkies, which is hardly likely to improve relations in its ongoing negotiations. What’s more, it threw up an apparently rather blatant case of double standards. Only a few weeks ago, Mark Rogers, Birmingham City Council CE and also President of SOLACE (Society of Local Authority Chief Executives) was describing to a SOLACE Summit audience how he was “fed up of being treated [by central government] like a child, when the organisation I work for, the partners we engage with, and the communities we serve are not children.” (my emphasis)).

Now, I don’t know what part Birmingham’s CE played in preparing the WMCA bid or whether he’s even seen the bid document. But I would suggest there are few quicker ways of getting ‘communities’ to feel they are being treated like children than to tell them that something that’s manifestly going to affect all their lives is none of their business.

The big irony here, however, is that, while the Treasury and WMCA disagree over the responsibility for the secrecy of the latter’s bid details, on the general PPP principle of the Public’s Proper Place their views are identical, as we saw over what promises to be the interesting issue of devolution referendums.

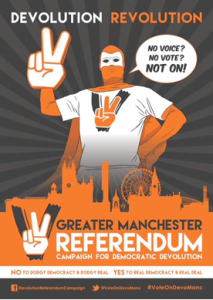

On October 25th, as part of its inquiry into the Cities and Local Government Devolution Bill, the Commons Communities and Local Government Committee held an evidence session at Manchester Town Hall. Following a Q & A with members of the public, the MPs heard from several leaders of the GMCA boroughs, but also from the Greater Manchester Referendum Campaign for Democratic Devolution. As with all its devolution programme, in this feature too Manchester sets the pace for the rest of the country.

It was launched back in January, two months after the announcement of ‘Devo Manc’, the first phase of the GMCA’s extensive devolution deal, part of which entailed having a directly elected mayor, who in interim form took office in June. The elected mayor issue provided a focus for the referendum campaign, but its organisers insist that it’s not devolution per se they’re opposed to, but devolution by diktat.

They argue that “ordinary people” should have the basic democratic right to have a say in “any changes, welcome or otherwise, to the way they are governed”. By contrast, the existing devolution package is conditional on its “imposition on the people of Greater Manchester, without any reference to their views whatsoever, of a directly elected mayor – a form of government which … has been either directly rejected by voters or by local councils themselves for their own areas.”

At which point, it may be tiresome but nevertheless useful – as we’re bound to be hearing a lot more of them – to take a brief terminological break to clarify just which of these kinds of polls are technically referendums and which aren’t. The 2012 metro-mayoral ones just alluded to definitely were: a policy enacted in government legislation but referred to local electors to approve or reject. So too are the council tax referendums that councils nowadays must hold, and win, if they wish to raise council tax by a higher percentage than that specified by the Government.

However, “having a say”, as demanded by the Manchester Referendum Campaign, sounds like and would be a non-binding consultative ballot – and likewise the highly significant vote promised to County Durham electors on the county’s share of the recently announced North East devolution deal.

Like the visiting MPs, GMCA leaders – several of whom, including Sir Richard Leese, were handed a severe kicking in the 2008 congestion charge referendum – will have heard Referendum Campaign spokesman David Fernandez-Arias attack their “back-room deals”, with “no public awareness, no public consultation, no democratic engagement, no scrutiny and no impact assessment.”

And the threat: “There are 17 priorities [GMCA indicators chosen to assess the devolution deal’s impact] and none concern improving democratic participation by the public. We will target leaders’ wards in [next May’s] elections just by canvassing and publishing results of what people think.”

It seemed appropriate in Rugby World Cup Final week that, immediately following this dangerous referendum talk, the DCLG should proverbially get its retaliation in first – a spokesman asserting that “local leaders had a mandate to make decisions for their areas and any opposition to them could be expressed through the ballot box”. And that was before County Durham’s announcement, so whatever the government and obviously some council leaders might hope, it’s already proved not the last word on the matter.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.