Louise Reardon and Greg Marsden

Rapid changes are underway in mobility systems worldwide, including the introduction of shared mobility solutions, Mobility as a Service and the testing of automated vehicles. These changes are driven by the development and application of ‘smart’ technologies such as smart phone platforms and real-time data sensors embedded in infrastructure. Transitions to these technologies present significant opportunities for countries, cities and rural areas alike, offering the tempting prospect of economic benefit whilst resolving today’s safety, congestion, and pollution problems.

Rapid changes are underway in mobility systems worldwide, including the introduction of shared mobility solutions, Mobility as a Service and the testing of automated vehicles. These changes are driven by the development and application of ‘smart’ technologies such as smart phone platforms and real-time data sensors embedded in infrastructure. Transitions to these technologies present significant opportunities for countries, cities and rural areas alike, offering the tempting prospect of economic benefit whilst resolving today’s safety, congestion, and pollution problems.

Yet while there is a wealth of research considering how these new technologies may impact on travel behaviour, improve safety and help the environment, there is a dearth of research exploring the key governance questions that the transition to these technologies pose in their disruption of the status quo, and changes to governance that may be required for the achievement of positive social outcomes.

Our new edited collection, published this week, aims to step into this void and in doing so presents an agenda for future research and policy action. The book brings together a collection of internationally recognised scholars, drawing on case studies from around the world, to critically reflect on three primary governance considerations:

- The changing role of the state both during and post-transition:

It is clear that smart mobility is bringing a new set of actors to the transport arena. These actors include global technology companies like Google and Apple; (transport) service aggregators such as Uber and Lyft; and firms specialising in artificial intelligence, automation and robotics who are working with incumbent providers to change the nature of existing goods and services (for example, BMWs partnership with Mobileye). This expanded and increasingly complicated multi-level network of actors has the potential to change the nature of the state’s role as a provider of services, but also challenges its existing relationships and position in transport governance networks more broadly.

- The voices shaping the smart mobility discourse:

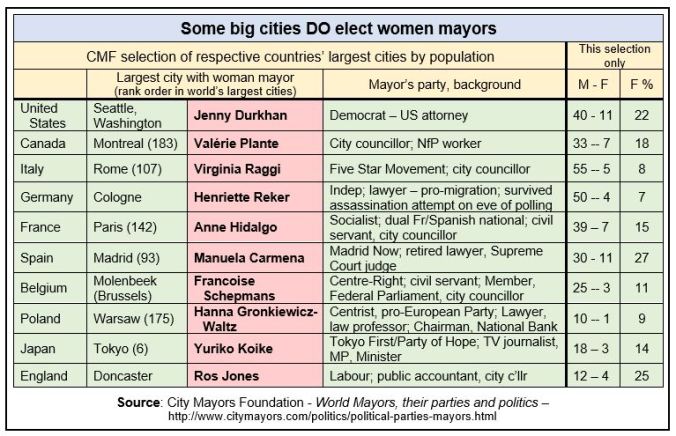

There inevitably exist asymmetries of power within governance networks; not all members are equally reliant on the resources of others to achieve their goals, and therefore not all voices receive equal attention. The question of who gets to participate is therefore critical to understanding how agendas surrounding smart mobility, its implementation, and outcomes will emerge.

- The implications for the state’s capacity to steer networks and outcomes as a result of these transitions:

Transitions have the potential to challenge or change forms of state capacity; the ability of the state to exercise its power within a network of actors in order to ‘set the rules of the game’ and steer policies towards chosen outcomes. For example, the smart mobility transition has developed during a period of significant fiscal re-adjustment following the global financial crisis of 2008. As Gardner (2017, 158) notes, such pressures have led to ‘market-driven approaches to co-ordination…growing in importance in comparison to state-driven models’. It is within this context then that we have to understand where within government there is the capacity to steer the mobility transition and what factors contribute to building rather than eroding that capacity.

On focusing on these three areas, the book concludes that governance is, and will, play a critical role in shaping the outcomes of smart mobility transitions, and argues that at present there exists a critical window of opportunity for researchers and practitioners to shape what these governance mechanisms should look like, and that this opportunity must be seized upon before it is too late.

Governance of the Smart Mobility Transition is edited by Greg Marsden and Louise Reardon and was published by Emerald this week. To get a 30% discount on purchase, use the code: EMERALD30

Louise Reardon is a lecturer at the Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham. Louise’s research focuses on a range of governance and public policy issues and questions; including dynamics of agenda setting, policy change, policy implementation, multi-level governance, depoliticization, and on the politics and policy of wellbeing. As co-chair of the WCTRS Special Interest Group on Governance and Decision-Making Processes, she is keen to grow the community of scholars critically engaged in understanding and challenging the status quo of transport policymaking.

Louise Reardon is a lecturer at the Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham. Louise’s research focuses on a range of governance and public policy issues and questions; including dynamics of agenda setting, policy change, policy implementation, multi-level governance, depoliticization, and on the politics and policy of wellbeing. As co-chair of the WCTRS Special Interest Group on Governance and Decision-Making Processes, she is keen to grow the community of scholars critically engaged in understanding and challenging the status quo of transport policymaking.

Greg Marsden is Professor of Transport Governance at the Institute for Transport Studies at the University of Leeds. He has researched issues surrounding the design and implementation of new policies for over 15 years covering a range of issues. He is the Secretary General of the World Conference on Transport Research Society and the co-Chair of the Special Interest Group on Governance and Decision-Making. He has served as an advisor to the House of Commons Transport Select Committee and regularly advises national and international governments.

Greg Marsden is Professor of Transport Governance at the Institute for Transport Studies at the University of Leeds. He has researched issues surrounding the design and implementation of new policies for over 15 years covering a range of issues. He is the Secretary General of the World Conference on Transport Research Society and the co-Chair of the Special Interest Group on Governance and Decision-Making. He has served as an advisor to the House of Commons Transport Select Committee and regularly advises national and international governments.

Dr Catherine Durose is a Reader in Policy Sciences at INLOGOV. She undertakes research, teaching and impact work on urban governance and public services, with particular interests in participation, intermediation and co-production. She is part of Citizens UK: Birmingham’s Leadership Group and a member of Citizens UK National Council.

Dr Catherine Durose is a Reader in Policy Sciences at INLOGOV. She undertakes research, teaching and impact work on urban governance and public services, with particular interests in participation, intermediation and co-production. She is part of Citizens UK: Birmingham’s Leadership Group and a member of Citizens UK National Council.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government.

Chris Game is a Visiting Lecturer at INLOGOV interested in the politics of local government; local elections, electoral reform and other electoral behaviour; party politics; political leadership and management; member-officer relations; central-local relations; use of consumer and opinion research in local government; the modernisation agenda and the implementation of executive local government. Catherine Mangan is Director of INLOGOV, co-convenes the Win Win network at the University of Birmingham, and facilitates national leadership programmes including

Catherine Mangan is Director of INLOGOV, co-convenes the Win Win network at the University of Birmingham, and facilitates national leadership programmes including

Yulei Lei graduated from INLOGOV in December 2017 with an MSc in Public Management. She is from South West China.

Yulei Lei graduated from INLOGOV in December 2017 with an MSc in Public Management. She is from South West China.