Cllr Ketan Sheth

Stories of long waits for NHS treatment are rarely out of the news. I am only too mindful that behind those headlines are real people and families who rely on planned care, emergency treatment, and a complex mix of outpatient and specialist services.

In Brent and across north-west London, the number of people waiting for an orthopaedic operation, according to the NHS, has increased by around 30% since April 2022. Whilst procedures like hip or knee replacements are not usually considered to be time critical, waiting for treatment can severely affect a person’s quality of life. Many conditions can, indeed, worsen over time, making treatment and recovery that much harder.

There is, however, some good news for people living in north-west London who find themselves on the waiting list for orthopaedic operation.

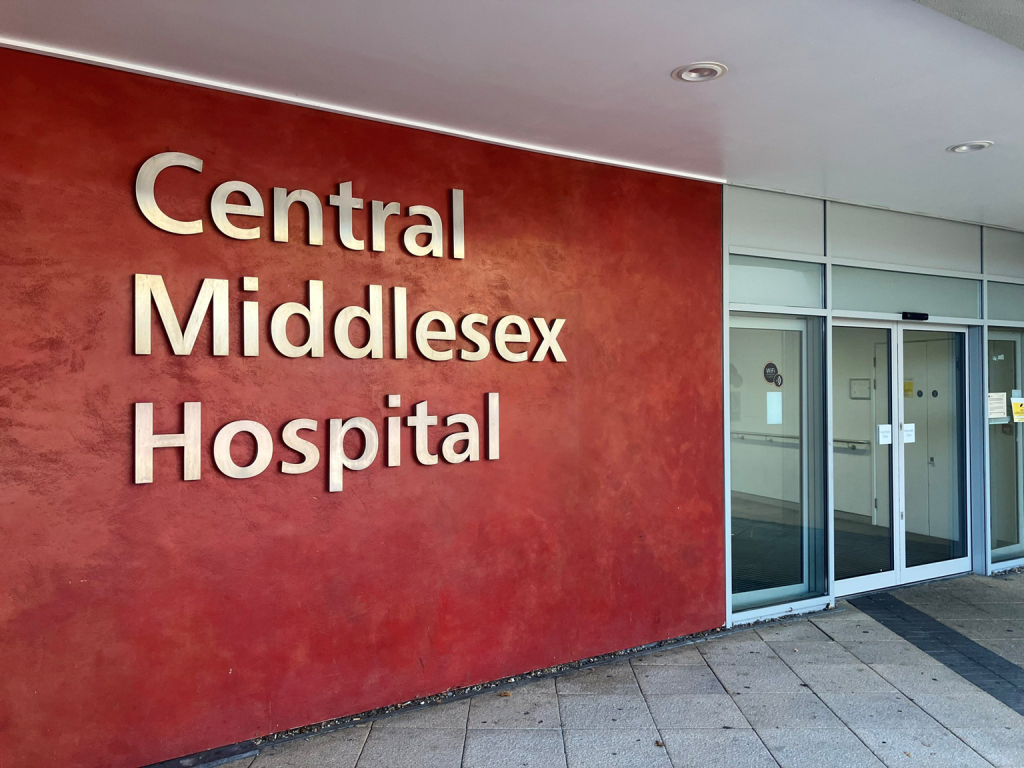

In December, an Elective Orthopaedic Centre, a new purpose-designed centre of excellence for orthopaedic surgery, was opened at Brent’s Central Middlesex Hospital (CMH). Since CMH does not provide emergency care, any planned operation is far less likely to be postponed due to emergency pressures.

The new centre is managed by London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust (LNWUH), in partnership with three other hospital trusts in north-west London. Between them, they manage 12 hospitals in north-west London, serving a very diverse population of 2.2 million across eight London boroughs.

The model of care that the new centre works to, is simple, but effective — wherever a patient lives in north-west London, their operation will now take place at the new centre. Care is overseen by the consultant from their local hospital, who are already well practised and expert in what they do, joins them at the new centre to do the operation on the day. The rest of their care — before and after operation — takes place at their local hospital, in their community, or online at home.

But since CMH does not provide emergency care, might that be a concern for a patient if there are complications during an operation? Well, the evidence from, for example, the orthopaedic centre at Epsom Hospital, which has been running for the past decade and performs one of the largest numbers of hip and knee replacements operations, suggests that complications requiring emergency care are exceptionally rare.

However, for many patients, CMH may not be the easiest place to get to and so free transport is provided for those who need it. Also, for these who prefers not to travel to CMH for their operation, some procedures will continue to be provided in their local hospitals, though the new centre will treat them quicker.

The new centre is, therefore, a fast-track surgical hub, dedicated to routine orthopaedic operations. As for patients with more complex needs, the NHS anticipates that they will also benefit from shorter waiting times as the new centre will free up capacity in other north-west London hospitals. With this model of care, it is expected that many more patients will be treated much quickly, have shorter hospital stays, a better experience and follow-up care.

As Chair of the North West London Joint Health Scrutiny Committee, I have seen an enormous amount of work that went into making the new £9 million centre a reality. Clinicians and other NHS staff from across the four trusts worked with GPs, residents, and other stakeholders to develop a detailed plan, including the funding model, affordability, capacity, faster and fairer accessibility, and length of stay. The plan was then subjected to rigorous scrutiny at my committee. Additionally, a further 2,000 individuals and organisations contributed to a public consultation.

Indeed, the four trusts worked in partnership with my committee. This ensured that organisational and geographical boundaries did not get in the way of our shared commitment to delivering equitable services and continuous improvements at scale for our residents across north-west London.

They could, of course, have looked at a hybrid model combining NHS and private care and it is arguable this would have more capacity. But the priority was clearly to get the new centre up and running quickly and negotiating a model like that would have taken time. I know many will welcome the model as it is, and it is clearly likely to make a difference for our residents. All this shows what can be achieved when different parts of the NHS, local government and residents come together, dare to challenge, and think differently. Addressing orthopaedic waiting lists will significantly improve many people’s quality of life. As we start 2024, that’s certainly some good news for people in living across north-west London.

Cllr Ketan Sheth chairs the North West London Join Health Scrutiny Committee