Chris Game

Literally minutes before I was going to email this already over-lengthy blog, I had my attention drawn to Birmingham’s rather paltry 5.4 score and 4th-from-bottom ranking on the HAYPP vape retailers’ ‘smell score’ scale – pretty well what it sounds like: UK cities ranked on perceived cleanliness. It seemed so obviously distorted by the lengthy bin collection strike and consequently not a lot better than Leeds’ 4.2, rather than up with at least, say, Newcastle (7.4) or even Liverpool (8.2). But, apart from those few lines, I let it pass.

So, on to my initial topic, which, as it happens, kicks off with some equally basic stats. Someone asked me recently – albeit after I’d slightly steered the conversation – if I knew whether (m)any of the several hundred new Reform UK councillors elected in the recent local elections (that I’d written about in a recent INLOGOV blog) had already left the party.

I had to waffle a bit – after all, the 677 ‘new’ ones had taken Nigel Farage’s party’s national total to just over 850, and some/many undoubtedly shocked themselves. But I did happen to know that the number of recent resignations/suspensions/expulsions was already into double figures. To which I was able gratuitously to add that the party had also ‘lost’, at least for the time being, two of its six MPs.

Which might seem to suggest either that I have a particular academic interest in Farage’s indisputably fascinating party or that I’m some kind of political nerd – to neither of which I’ll readily admit.

No, the explanation for my having acquired this arcane knowledge is that for at least 30 years now I’ve known/known of (nowadays Baron) Mark Pack, his captivation with all things electoral, and his enthusiasm for sharing that captivation – dating back to when he was at the University of Exeter, just up the A38 from the University of Plymouth, original home of ‘(Colin) Rallings & (Michael) Thrasher’ (definitely local government statistical junkies), and now itself home of their internationally renowned Local Government Chronicle Elections Centre, and its/their matchless annual Local Election Handbooks.

Naturally, R&T’s interests and path-breaking publications focus primarily on local government elections. Those of (nowadays) Lord Pack of Crouch Hill (but Mark hereafter) include the Liberal Democrat Party, of which he’s currently an extremely active President; the House of Lords, and, as ever, political opinion polls, about all of which he writes invariably fascinating weekly newsletters; in addition to reporting on almost anything electoral. This and more he shares on his exceedingly lively website, the recommendation of which (to any readers unfamiliar with it) is the main purpose of this blog.

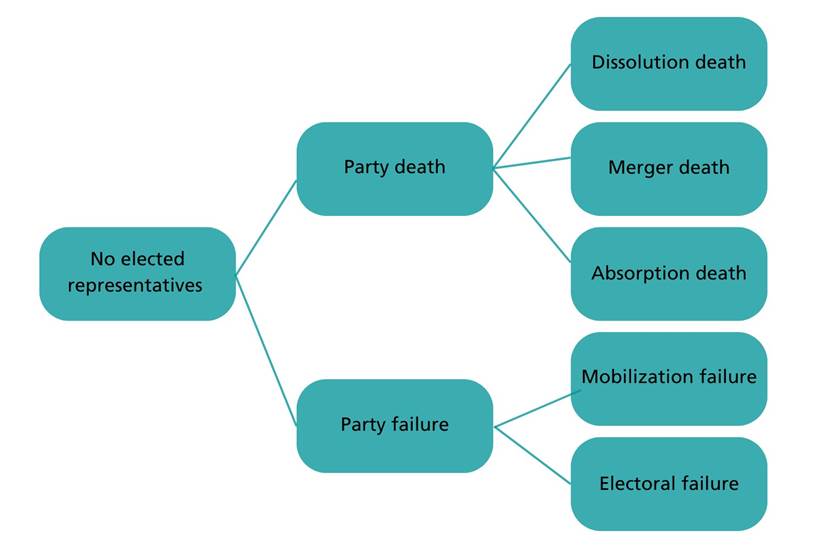

And so, belatedly, back to those disappearing Reform UK councillors. It’s the sort of phenomenon that Mark Pack revels in – the numbers, the reasons/circumstances, it’s all perfect material for a near-daily political diarist. He naturally keeps a running list of councillors “shed by Reform UK” since the May elections, the most recent updating of which at the time of typing this paragraph being, I think, on July 7th, when the departee figure had reached a quite striking 11.

They comprised five straight resignations as councillors, two expulsions by Reform, three suspensions by the party, one of whom subsequently quit, and one who’d decided they’d prefer to be an Independent.

As for the (female) Reform UK councillor charged with assault and criminal damage, for instance – well, it was covered, naturally, in Mark Pack’s diary on June 30th, and she’ll shortly be “appearing before magistrates”. And, as the Crown Prosecution Service publicly emphasised, it’s “extremely important that there be no reporting or sharing of information online which could in any way prejudice ongoing proceedings.”

Which brings us to the two of the all-time total of just six Reform MPs who already are no longer. First was Great Yarmouth MP Rupert Lowe, who back in March was suspended and reported to the police over alleged threats of physical violence towards the party’s Chairman, Zia Yusuf. And second, more recently, was James McMurdock, who “surrendered the party whip” a few weeks ago over, as The Guardian delicately put it, “questions of loans totaling tens of thousands of pounds.”

The key, albeit belated, point of this blog, however, is the multifaceted contribution to our political world of Mark Park himself, rather than ‘here-today-gone-tomorrow’ MPs. Yes, he’s a copious diarist, but so much more. In particular, there’s his arguably greatest single contribution to our academic political world: the phenomenon that is what I still think of as his ‘PollBase’, but which comparatively recently has acquired the handle PollBasePro.

If you’re writing anything at all concerning our political world in the 90-plus years since 1938/39 – yes, before the start of World War II – and you need to know or even get a sense of the state of UK public opinion on a virtually month-by-month, and latterly week-by-week, basis, just Google either title, and it’s there, instantly accessible and downloadable. Yes, completely free – all Mark asks is that you point out any mistakes (!) and have the decency to acknowledge the source.

It’s a fabulous resource, easily worth – pretty obviously – a blog on its own, but all it’s going to get on this occasion is this abbreviated reference, kind of explaining why I’ve structured this blog in the way I have. That reference comes from p.2 of the dozens of pages, when the only pollster was Gallup and the only poll publisher the News Chronicle (1930-60, when it was “absorbed into the Daily Mail”).

From the start, in 1938, the sole question asked consistently was “Conservatives Good or Bad”, and, probably not surprisingly, throughout most of World War II, the Conservatives were overwhelmingly (75-90%) ‘Good’. Only from 1943 were questions asked about the other parties, and from the start Labour, polling consistently in the 40s, had a double-figure lead over the Conservatives, suggesting that voters were already clearly differentiating between the conduct of the war and the conduct of peace.

This came to a head in January 1946, when Labour, with 52.5%, outpolled the Conservatives by a massive 20.5%, a lead they’d never previously even approached and would do so just once again in the coming decades. Oh yes, and I was born at the very end of December 1945 – and, if only we’d known, my committed Tory-voting parents would have been deeply unhappy, and I’d have gurgled contentedly. Sorry about the length, but I had to squeeze that last bit in.

Chris Game is an INLOGOV Associate, and Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan. He is joint-author (with Professor David Wilson) of the successive editions of Local Government in the United Kingdom, and a regular columnist for The Birmingham Post.